Thomas Nuttall: Oklahoma's Lewis and Clark

Published August 2019

By Susan Dragoo | 30 min read

In History’s Footsteps

Nearly 200 years after Thomas Nuttall’s exploration of eastern Oklahoma, a writer and an artist retrace his steps on a ramble of their own.

By Susan Dragoo

Art by Debby Kaspari

Norman artist Debby Kaspari painted this natural rock formation, part of Wilson Rock, along the Arkansas River. It was named for William Wilson, who once operated a ferry near the site.

The Setting

The year is 1819, and the land we know as eastern Oklahoma is the dominion of the Osage. The few Europeans in this vast tract of country are French traders and trappers headquartered at Three Forks—where the Arkansas, Verdigris, and Grand rivers come together near present-day Muskogee. Only sixteen years have passed since the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory, and the wilderness west of the Mississippi River still excites curiosity among many. Earlier, President Thomas Jefferson had dispatched explorers to establish the territory’s boundaries and discover its flora, fauna, geology, and peoples. A few of those explorers passed through or near the land that will become Oklahoma, but the region nonetheless remains for the most part a mystery.

Enter an Englishman, on a privately funded expedition, exploring streams, mountains, prairie, and forest. He had arrived in the U.S. in 1808 at age twenty-two to satisfy his curiosity about North American plants, at the time largely undescribed by the scientific community. Having already botanized in the Northeast, into the Northwest as far as the mouth of the Yellowstone River, and deep into the South, he now seeks to discover the flora of the West on his way to reach the Rockies via the Arkansas River Valley, where he anticipates botanical treasure. Branded absent-minded by his traveling companions, Thomas Nuttall is one of the first scientists to explore Oklahoma, leaving a detailed picture of its life and land in A Journey of Travels into the Arkansas Territory During the Year 1819, published in 1821. It was reissued in 1979 in an edition published by the University of Oklahoma Press and edited by its emeritus director, Savoie Lottinville.

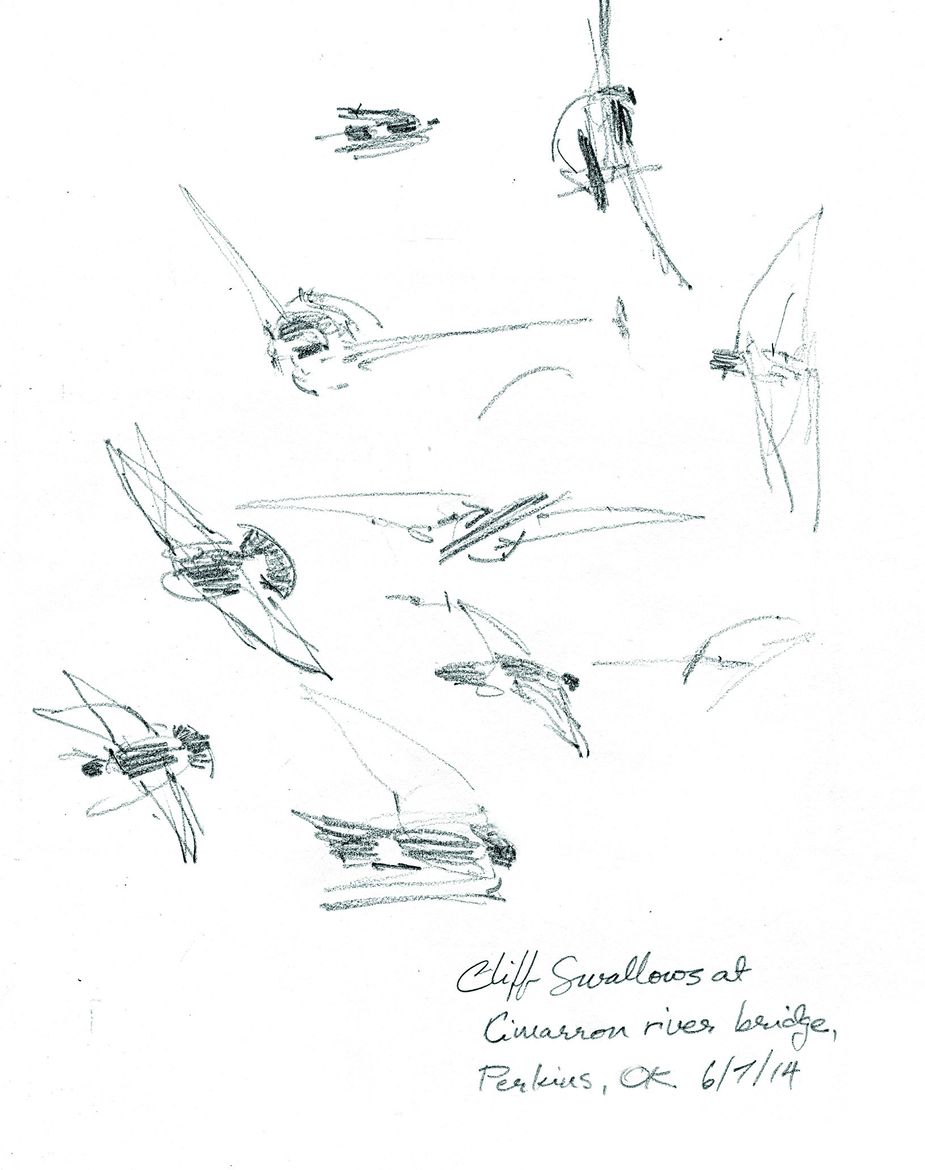

Though Thomas Nuttall eventually became a respected ornithologist, he primarily focused on flora during his time exploring the land that became eastern Oklahoma. Debby Kaspari’s pencil sketch, left, is of cliff swallows near Perkins. These compact migratory birds nest in Oklahoma in spring and summer before flying to South America in the fall to winter there.

Point de Sucre

[April 24] Rising . . . out of the alluvial forest, is seen from hence . . . a conic mountain nearly as blue as the sky, and known by the French hunters under the name of Point de Sucre, or the sugar loaf. Thomas Nuttall

Ten miles east of present-day Poteau, Sugar Loaf Mountain, 2,564 feet above sea level, was Thomas Nuttall’s first recorded sight of what would become Oklahoma. He had just arrived at Fort Smith in a pirogue, or large dugout canoe, after a seven-month journey from Philadelphia along the Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas rivers. The Fort Smith garrison was located at Belle Point, a picturesque promontory where the Poteau and Arkansas rivers come together. The Army’s westernmost outpost, Fort Smith was established in 1817 to keep peace between the Cherokee and Osage. It was literally the edge of the frontier.

Our own ramble begins where Nuttall first saw Oklahoma rising over the western horizon. I am partnered with Norman artist Debby Kaspari—whose prolific nature paintings and sketches make her something of a naturalist in her own right—to retrace Nuttall’s path.

What remains of the natural environment Nuttall extolled? On a rainy April 24 nearly two centuries later, we stand near the water’s edge on Belle Point’s black stone landing and look in the distance for Sugar Loaf. Today, the Fort Smith National Historic Site graces this elevation, and the locks and dams of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System now control these waters, maintaining a minimum depth for cargo vessel navigation.

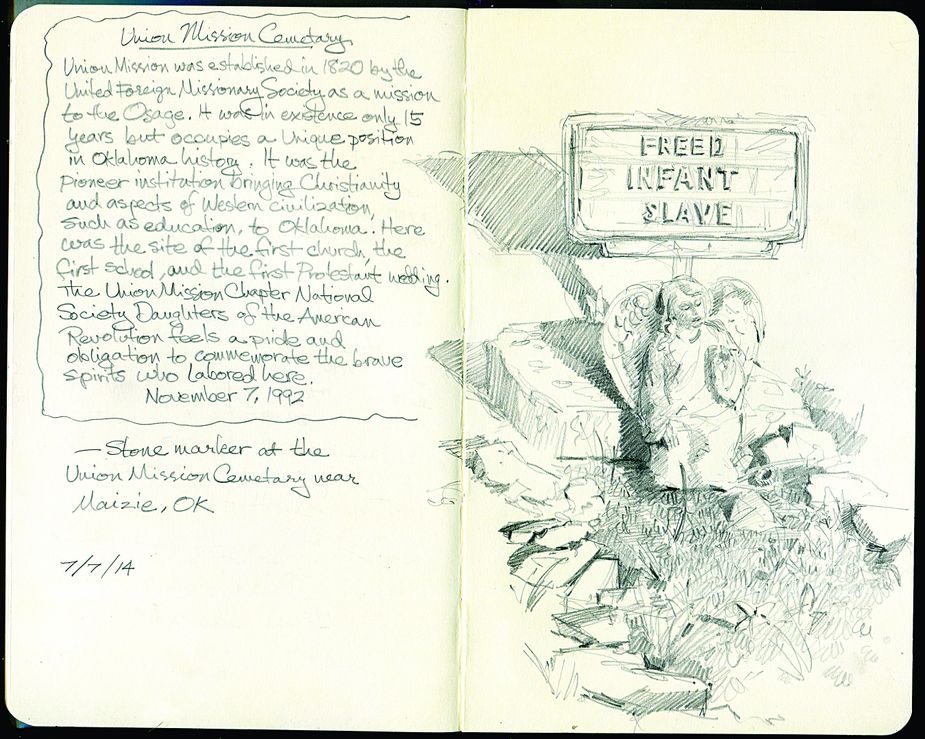

Debby Kaspari sketched this grave marker at the Union Mission Cemetery near Mazie. Although Union Mission was established in 1820, after Nuttall passed through the area, he crossed paths with missionaries who were scouting its location.

Nuttall remained at the fort for several weeks, exploring the adjoining prairie and the banks of the Poteau River and discovering new plant species, such as Nemophila phacelioides Nutt., more commonly known as largeflower baby blue eyes. Traveling southeast, he remarked again on the view of Sugar Loaf and what he called “the Cavaniol,” which appeared to him the higher of the two. Today, Cavanal Hill is billed as “the world’s highest hill.” At 1,999 feet above sea level, 565 feet lower than Sugar Loaf, Cavanal stands one foot short of the American designation for a mountain’s minimum height.

Low clouds dash my hopes of replicating Nuttall’s first sight of Oklahoma on the 195th anniversary of his arrival, but on a clear day, I can easily see both peaks from Interstate 40 near Fort Smith.

Before continuing west, Nuttall traveled to the Red River with soldiers tasked to remove white squatters in preparation for the relocation of Choctaw Indians from Mississippi. He returned to the garrison in late June, then left for Three Forks on July 6 in a boat with French-Canadian trader Joseph Bogy, camping the first night on a sandbar to avoid mosquitoes, a precaution that would become routine on this journey.

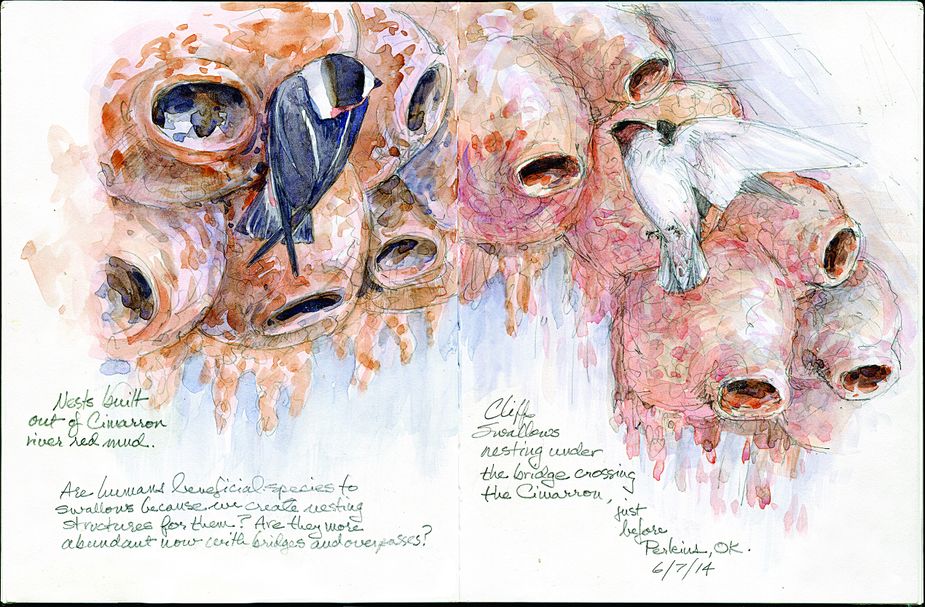

Like mud daubers, cliff swallows build colonies of mud nests on a variety of human-made structures. Debby Kaspari and Susan Dragoo encountered these under a bridge crossing the Cimarron River near Perkins.

Up the Arkansas

[July 7] Not far from the place of our encampment, on the left, we passed the Swallow (or Hirundel) rocks, a projecting cliff, about 150 feet high, adorned with bushes of cedar, in the centre of which there appears to be an entrance into a cavern, and several other fretted excavations scattered over with clusters of martin nests. Thomas Nuttall

As we drive west into Muldrow on U.S. Highway 64, it is easy to miss the Wilson Rock Road sign. Five miles south, the road becomes a narrow lane running up to the Arkansas River and a graffiti-covered stone overlook. This is Wilson Rock, which Nuttall passed on the second leg of his journey and, according to Lottinville, is the spot Nuttall called “the Swallow rocks.”

Nuttall’s passage predates the bluff’s naming for William Wilson, who operated a ferry here later in the nineteenth century. There is barely a breeze off the river when we arrive in the heat of the day. A crumbling, mud dauber-infested picnic table serves well enough for a sandwich lunch, then we climb over a guardrail to the sandstone expanse. Debby sets up her easel next to some local fishermen, and I wander off to look for Wilson’s autograph. Legend has it that he carved his name into the rock, and the signature is still there, at the outcrop’s edge. What is assumed to be Wilson’s handprint is embedded in the stone next to his name—likely carved, but looking more like it was pressed into wet sand before it hardened into stone.

I still have questions about Wilson’s Rock, which leads me to contact archaeologist Dennis Peterson, manager of the Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center, located across the river from Wilson Rock. He confirms that Swallow Rock was a different site a few miles upriver and leads us on a hike to see it. Little remains. Walking through brambles and beautyberry bushes to an overlook, we find a hole where the bluff was quarried for limestone for the construction of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System in the early 1960s.

Nuttall’s party hunted bison, gathered plums, and dined on turtle eggs as they traveled, soon passing the outlet of the Canadian. This confluence now lies within the Sequoyah National Wildlife Refuge, which mimics what the historically shallow and meandering Arkansas looked like in Nuttall’s day. The river would seasonally create oxbow lakes, sloughs, and shifting sandbars. Here, places like Sally Jones Lake and Horton’s Slough re-create that habitat.

Nuttall and Bogy arrived at Three Forks on July 14. It was a busy place, supporting four principal trading posts along the banks of the Verdigris in the vicinity of the present-day town of Okay. A marker stands at the edge of town on State Highway 16, commemorating the history of the Three Forks area. There is otherwise no indication of what once stood on this spot.

“Nothing existed here in Nuttall’s time except Indian encampments, trading posts, and mounds,” says Russell Lawson, history professor at Bacone College in Muskogee and author of The Land Between the Rivers, a 2004 account of Nuttall’s 1819 journey. “It was a very pristine environment that he came into with Indian tribes and traders and trappers.”

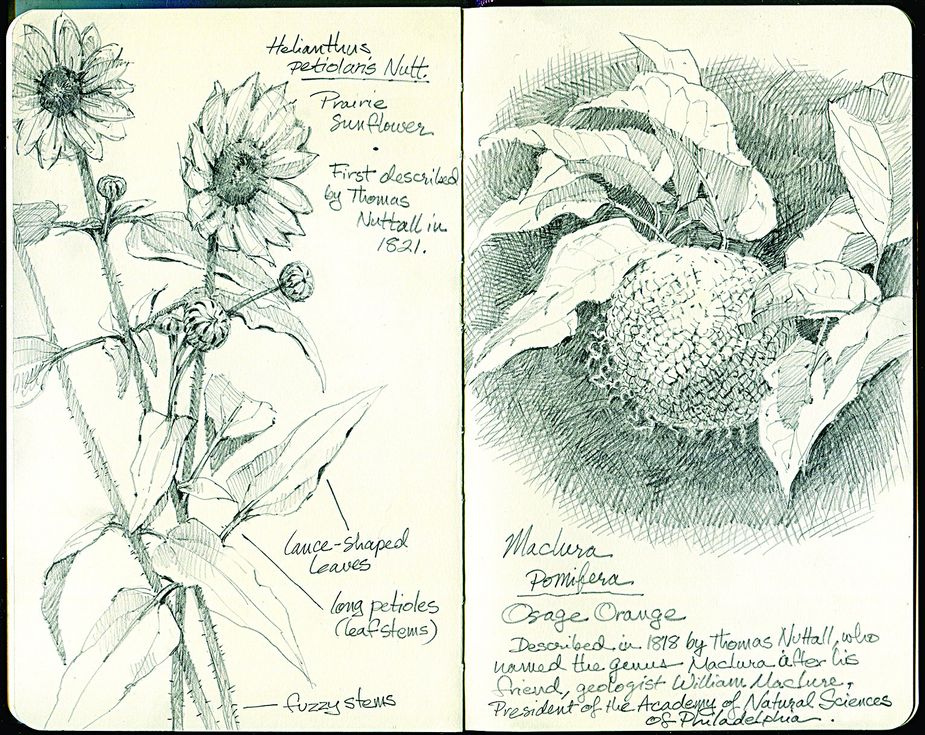

Helianthus petiolaris, a prairie sunflower, and Maclura, a member of the mulberry family, both were recorded by Thomas Nuttall during his 1819 journey through what would become eastern Oklahoma.

Three Forks and the Salt Works

[July 14] This morning . . .I walked over a portion of the alluvial land of the Verdigris, the fertility of which was sufficiently obvious in the disagreeable and smothering luxuriance of the tall weeds, with which it was overrun. Thomas Nuttall

The morning he arrived at Three Forks, Nuttall hurried out to explore the neck of land between the Grand River and the Verdigris. He noted a canebrake, a dense growth of cane more than two miles thick, along the lower side of the Grand River. There, he discovered a new species of prairie sunflower, Helianthus petiolaris, in the adjoining “great Osage prairie” running northwest from Okay into Wagoner, Tulsa, and Osage counties.

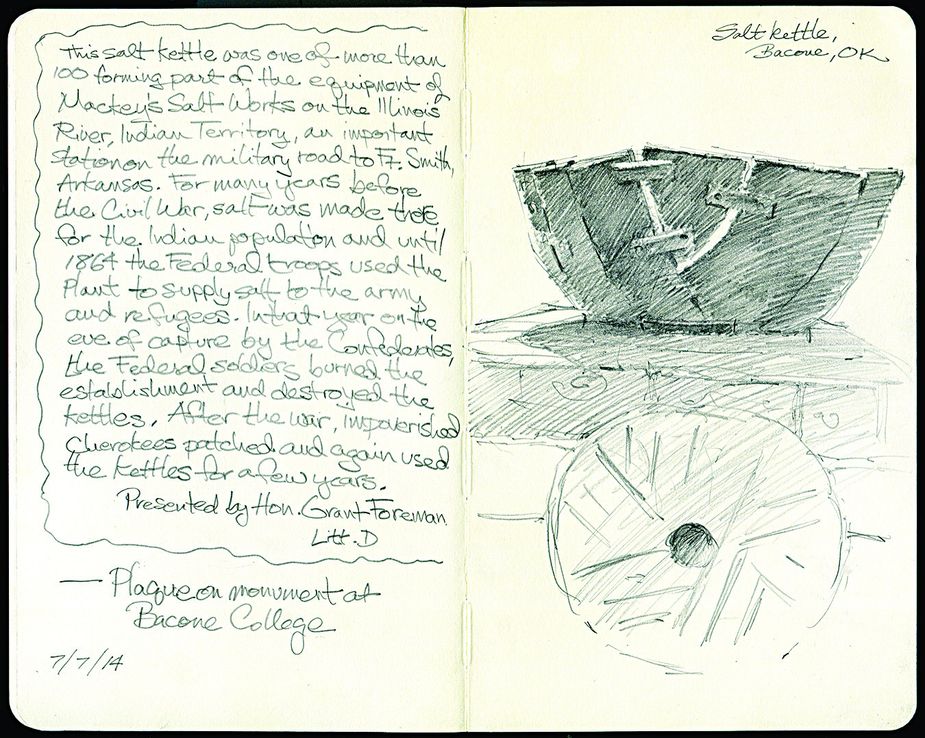

On July 17, Nuttall canoed up the Grand River to visit a saltworks, where brine from a nearby salt spring was boiled in iron kettles, extracting the mineral for use in preservation and cooking. Today, we give little thought to salt or its sources, but its importance in the lives of the pioneers is clear from the many towns and streams across the United States named Saline or Salina. The flowing spring Nuttall visited was five miles northeast of what is now Mazie, in Mayes County.

Might this salt spring still exist? It seems the Mazie spring must have been flooded when the Grand River was dammed to create Fort Gibson Lake. But my search leads to another discovery: The spring was located near Union Mission, the first Protestant mission in Indian Territory, established in 1820 to serve the Osage. The mission also was the site of the Territory’s first school building and printing press, and its location near the Texas Road, which generally was aligned with present-day U.S. Highway 69, brought many travelers.

By 1836, Union Mission was closed, its buildings abandoned. Today, only a marker stands on the site across a lonely road from Union Mission Cemetery. I leave Debby sketching there and wander around in the forest beyond the marker, but it is private property, and I think better of walking farther into the deep woods. Returning, I climb the steep cemetery steps to find Debby at work. She points out, among two dozen graves, a metal marker reading “Freed Infant Slave” adorned by an angel figurine.

Before leaving the saltworks, Nuttall reports “a slight attack of the intermittent fever.” A few years before, he had contracted malaria, then common but not fully understood. He suffered another attack after returning to Three Forks, and Lottinville notes that Nuttall “was now a victim of malaria at a more advanced stage than he yet knew.” He would suffer its effects for years to come.

A salt kettle Debby Kaspari sketched at Bacone College in Muskogee dates to the Civil War era and originated at Mackey’s Salt Works, an important supplier for tribes and Civil War troops near the Illinois River.

Deep Fork

On August 11, Nuttall’s push toward the Rocky Mountains continued. He rode southwest across the prairie on horseback with a Mr. Lee, who had trapped and hunted in the area for about eight years. The two soon struck the Deep Fork River in present-day Okmulgee County, then followed its course northwest toward the Cimarron River—known then as the First Red Fork or Salt River—believing it would be an efficient route into what is now southeastern Colorado.

Today, the Deep Fork National Wildlife Refuge south of Okmulgee protects 9,702 acres of habitat in the Deep Fork river bottom. The Cussetah Bottoms Trail provides an elevated boardwalk through the bottomland hardwood forest for wildlife viewing.

For the next two weeks, the pair struggled to make progress, plagued by the excessive heat and Nuttall’s fever, delirium, and increasing weakness. A large wound rendered Lee’s horse unfit for travel, and green blowflies filled their clothes with maggots and penetrated the horses’ wounds. Lee urged returning to Three Forks, but the idea filled Nuttall with “deep regret,” and he opposed it, “whatever might be the consequences,” in his determination to continue to the Rockies.

Eventually, they made better progress. By August 30, Nuttall was a little recovered, and they ventured into the prairie hills. Lee killed two bison that evening, “but neither of them were fat, or anything like tolerable food,” Nuttall wrote. The botanist spent a night of “great misery and delirium.” Even so, the next day, the pair moved on a few miles.

In his journal, Nuttall did not appear to enjoy his trek through the Cross Timbers region, noting its “impenetrable” and “horrible” thickets.

Cross Timbers

[September 1] We proceeded about 10 miles over wooded hills, with the expectation of soon arriving at the Salt river, which we imagined to lie before us, either to the west or south-west, but were entirely deceived, and my companion now appeared to be ignorant of the country. We saw nothing far and wide but an endless scrubby forest of dwarfish oaks, chiefly the post, black, and red species. Thomas Nuttall

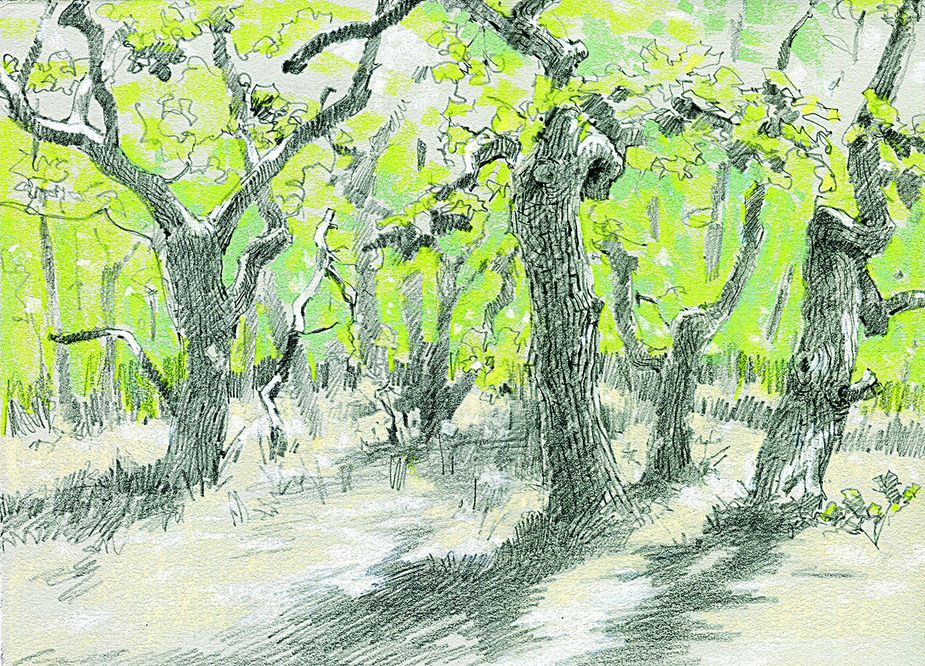

“The travelers had been in the Cross Timbers for much of the time since leaving the Arkansas, but here, they experienced some of its densest growth,” Lottinville wrote. Still an important part of Oklahoma’s ecosystem, these post oak woodlands stretch from southeast Kansas through a swath of Oklahoma and into north Texas. Though diminished over the past two hundred years, some large stands of old growth remain, and the largest known contiguous tract of ancient Cross Timbers is in the Okmulgee Wildlife Management Area along the Deep Fork River.

An expert on tree-ring dating, Dave Stahle is a geosciences professor at the University of Arkansas and founder of the Ancient Cross Timbers Consortium, a collaboration among conservationists in several states.

“The whole tract of woodland and grassland at Okmulgee has hardly changed since Nuttall visited in 1819,” says Stahle. “You cannot say that about many landscapes today.”

In that post oak forest, on a high ridge and in sweltering heat, we follow Bruce Burton, wildlife management biologist for the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, as he points out the twisted bark of the ancient trees in the Okmulgee WMA. Their relatively small size belies their age, says Burton. Even the oldest may not be very large.

“Look before you sit or put your hand down on a rock,” he cautions. “There are pygmy rattlers.”

Undaunted, Debby sits on a boulder to sketch the forest in pencil and pastel, and I take a side trip down a muddy road—nearly a trail—beneath the Red Oak canopy to the river. I am curious. An Okmulgee County childhood taught me the Deep Fork River is a thing best avoided, like riding a pump jack or lingering on the train tracks. There are snakes and gar and catfish hiding in the liquid mud of that red current. Now, as I push through the undergrowth to the river, I wonder if I’ve outgrown those fears. But standing on the riverbank, I can only think that I shouldn’t be out here alone, if at all. I drive back to the top of the ridge, admiring Nuttall’s determination all the more.

“One day in June 2014, Susan and I drove up to an abandoned highway bridge across the Cimarron River near Ripley. It’s on private property, but we got lucky; the owners were home and let us go out there,” says Debby Kaspari. “The day was gorgeous. I painted from the middle of the bridge where the railing crumbled and fell over the side, opening up the view. We saw egrets, cliff swallows, even a gar down in the water. It wasn’t too hard to imagine someone poling a skiff along the bank.”

The Cimarron

[September 3] Towards evening, greatly fatigued . . . we came upon the rocky bank of the First Red Fork or Salt river, which, though very low, was still red and muddy. Thomas Nuttall

The westernmost point of Nuttall’s journey is uncertain. Lottinville suggests it might have been near present-day Guthrie, but Lawson puts it between Guthrie and Perkins. Nuttall biographer Jeannette Graustein places it farther east, two days’ journey from the Cimarron’s confluence with the Arkansas, now under Lake Keystone. Regardless, Lee and Nuttall finally struck the Cimarron on September 3.

Abandoned bridges afford unhindered river observation. For a good view of the Cimarron, we find one in Payne County, a 1928 beauty closed for thirty-five years. Missing guardrails make it even better for Debby’s purposes, eliminating obstruction. It’s another day of temperatures nearing a hundred. Egrets rest on sandbars while turtles sun on piles of brush swept up against the bridge supports. A snake slips from the muddy bank into the water. Salt cedar’s pinkish-purple bloom gives color to what Nuttall called the “beaches,” which in the dry 1819 summer would have been salt-encrusted and devoid of vegetation. I watch the water’s red surface change with current, wind, and cloud shadows. The shiny sea-green body of a gar surfaces, then submerges, and I gaze with alternating waves of revulsion and curiosity.

Nuttall and Lee continued a few miles up the bank of the Cimarron, but on September 4, Lee’s horse was trapped in a gulley and left behind, and the pair was forced to turn back. With some difficulty, Lee found a large cottonwood tree and spent the next several days building a canoe for himself.

Return

[September 14] Fatigued with the sand-beaches, as hot and cheerless as the African deserts, I left the banks of the river. Thomas Nuttall

Lee launched his canoe September 8—Nuttall rode along the river banks—and they reached the Arkansas on September 9. The pair followed the Arkansas for a few days, and on September 12, with Nuttall unable to keep up, agreed to part.

North of Muskogee, we find the Arkansas much like the river of Nuttall’s day, since it is here the McClellan-Kerr begins to follow the course of the Verdigris to its terminus at the Port of Catoosa. On the river east of Haskell, we scramble beneath another abandoned bridge to walk along the hot, sandy beaches. The two of us imagine Nuttall—weak, sick, hungry—struggling to return to civilization. On September 15, he made it to Bogy’s trading post at Three Forks, which he referred to as “an asylum, which probably, at this time, rescued me from death.”

The Cross Timbers forest region was a scenic but formidable barrier for early explorers like Thomas Nuttall.

Epilogue

Thomas Nuttall returned to Philadelphia in 1820, where his expedition findings were well received. He became a lecturer at Harvard University, but his attraction to wilderness would not let him rest. In 1834, he resigned his post and traveled across the Rockies to the Pacific Northwest, later making two trips to Hawaii, visiting California, then sailing around Cape Horn and back to Boston.

Nuttall is respected as the most widely traveled and knowledgeable naturalist of his time, having dedicated thirty-four years to collecting, describing, and teaching about the flora of North America. It is hard to travel anywhere in the American West without seeing a plant that was named or collected by him. His 1819 journal has served as a valuable record of frontier settlements on the Arkansas and a source text for Arkansas and Oklahoma history. After returning to England in 1841, Nuttall died in 1859.

“Whether you think modern civilization has helped or hindered, it has definitely made the land completely different,” says Russell Lawson. “The gift Nuttall gives us is showing what Oklahoma was like before it was altered. What we see today is just one moment. Through Nuttall, we can try to recover the past.”

The landscape is different, yes—the impact of humanity is indeed pervasive—but there are places where the land itself is much the same. We can still find Nuttall’s Oklahoma in the shadow of the Sugar Loaf, the sandy beaches of the Arkansas, the salty banks of the Cimarron, and the twisted bark of the Cross Timbers.

Ramble On

Finding the destinations mentioned in this travelogue

Wilson Rock Road is eight-tenths of a mile east of Main Street/Highway 64B in Muldrow on U.S. Highway 64. Turn south on Wilson Rock Road and travel five miles until the road turns east along the river. William Wilson is buried in the cemetery on top of the bluff.

Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center, the only prehistoric Native American archaeological site in Oklahoma open to the public, is seven miles northeast of Spiro. (918) 962-2062 or okhistory.org/sites/spiromounds.php.

Sequoyah National Wildlife Refuge is approximately thirty-five miles west of Fort Smith, Arkansas, off Interstate 40. Take Exit 297 near Vian from I-40 and follow a county road three miles south to the refuge headquarters. (918) 773-5251 or fws.gov/refuge/sequoyah.

The Texas Road/Three Forks historical marker is on State Highway 16 south of Okay near the highway crossing of the Verdigris River.

Three Forks Harbor near the Port of Muskogee provides public access to the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System. (918) 682-7886 or threeforksharbor.com.

Deep Fork National Wildlife Refuge is east of U.S. Highway 75 between Okmulgee and Henryetta at 21844 South 250 Road. (918) 652-0456 or fws.gov/refuge/deep_fork.

Union Mission Cemetery is northeast of Mazie, east of U.S. Highway 69 on County Road N4335.

Three Rivers Museum is located at 220 Elgin Street in Muskogee. (918) 686-6624 or 3riversmuseum.com.

The Okmulgee Wildlife Management Area is on State Highway 56, 6.9 miles west of U.S. Highway 75. (918) 759-1816 or wildlifedepartment.com/facts_maps/wma/okmulgee.htm.

For information on the Ancient Cross Timbers Consortium, visit cavern.uark.edu/misc/xtimber.

For information on historic Oklahoma bridges, visit bridgehunter.com/ok.