Post Haste

Published June 2023

By Susan Dragoo | Photos by Susan Dragoo | 20 min read

The land still bears the faded scars of the old route: a swale through a pasture, a cut-down creek bank, a path worn bare through the forest. In some forgotten places, walled springs still flow near the rubble of rock buildings or graveyards of broken stones. They testify to the long-ago passage of the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoaches through what would become Oklahoma.

It’s been 160 years since the first two bags of mail on the route crossed the Poteau River into Indian Territory. Today, an excursion along Oklahoma’s 192 miles of the Butterfield trail is both time warp and treasure hunt. My husband Bill and I set out to retrace the Indian Territory section of the 1858-1861 Butterfield route, traveling the back roads of southeastern Oklahoma to discover what remains.

The Brazil Creek Bridge in LeFlore County is a pony truss span over a scenic spot near what was a nineteenth-century mail station.

The road began in Tipton, Missouri, at a terminus of the Pacific Railroad. At the time, long sea journeys were the easiest mode of travel from the East Coast to the newly populous west, and the nation needed a more efficient way to deliver the mail.

Enter Utica, New York, native John Butterfield. He was a veteran stagecoach man and a founder of the Railway Express company that eventually became American Express. In 1857, Butterfield secured from the Postmaster General a contract to set up the stage line and, in a year’s time, organized a network of coaches, drivers, horses, guards, veterinarians, blacksmiths, stables, and mules to cover the 2,800-mile mail route.

The Lime Arch Bridge in Pittsburg County near Hartshorne is a natural rock formation near Brushy Creek.

The first coach left Tipton on September 16, 1858, bound for San Francisco. After crossing Missouri, Arkansas, and Indian Territory, the route made a long traverse of Texas then skirted the Mexico border into California before turning north toward its final destination. The Postmaster General required delivery of the mail within twenty-five days, a goal Butterfield’s drivers often beat.

Before running the first stage, Butterfield made arrangements with Choctaw and Chickasaw citizens living on or near the road to maintain stands where teams of horses quickly could be changed out. In Indian Territory, there were a dozen official stations about sixteen miles apart, beginning with Walker’s Station at Skullyville near present-day Spiro. The trail then ran southwest on a diagonal near Latham, Red Oak, Wilburton, Higgins, Atoka, Boggy Depot, and Durant before reaching the site of Colbert’s Ferry at the Red River.

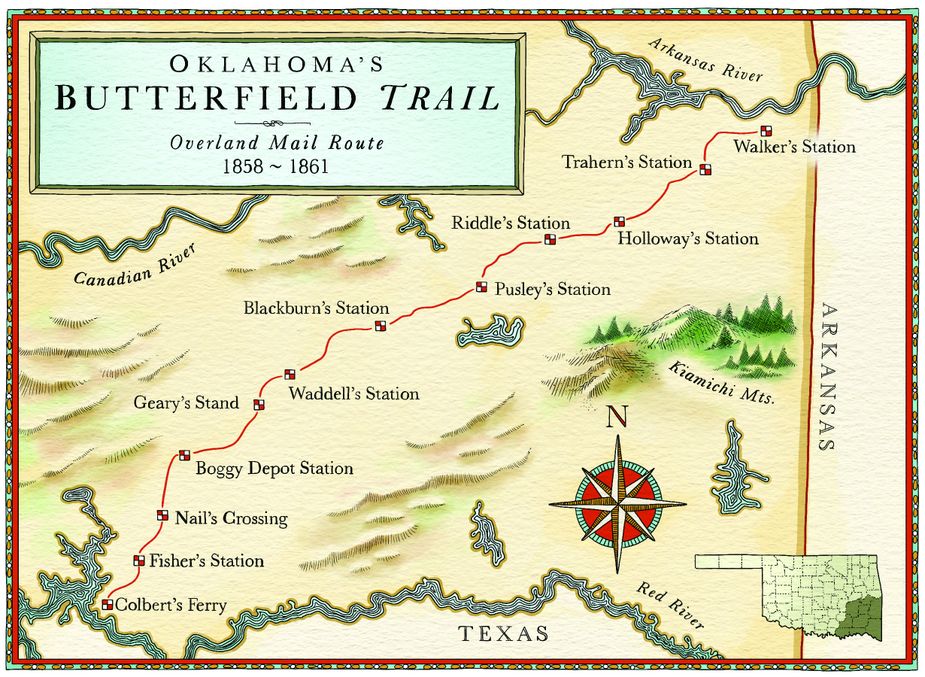

The Butterfield Overland Mail Route traveled 192 miles through Indian Territory. It originated in Missouri and ended in San Francisco.

One of the challenges of finding the old road today is that virtually all of it, except what’s been incorporated into modern roads, is behind barbed wire fences and locked gates. Luckily, the Oklahoma Historical Society placed roadside markers at station sites in 1958 to commemorate the trail’s centennial, and most of the markers still are intact and accessible.

The first Butterfield wagon arrived at 2:05 a.m. on September 19, 1858 in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and that’s where we begin our journey. The stagecoach forded the Poteau River and entered Indian Territory about 3:30 a.m. We leave Fort Smith through Arkoma, crossing the Poteau River bridge and following State Highway 9A.

Our first stop is Walker’s Station at Skullyville. Here on a quiet country lane once sat the Choctaw Agency, which was established in 1832 to distribute tribal allowances to citizens of the Choctaw Nation. The station was at the home of Choctaw Governor Tandy Walker, and his house stood on this hillside until it burned in 1947. Today, the spot would be easy to miss, but on Spring Road, a green sign for Roselawn Cemetery marks a turn-off. Here, a walk north along the street reveals a granite marker and a bronze plaque in a trace of the stagecoach road. Looking southwest from the marker, the depression in the earth left by the trail is obvious, and water still seeps down the hill from the spring house to the north. Oklahoma historian Muriel Wright, who was part of the 1958 entourage identifying marker sites, mentions in her report the tall trees giving the site an aura of dignity and importance.

Dog Creek Ranch in Poteau

The Skullyville cemetery is just west of the station. Wright noted that it was overgrown and unkempt, densely covered with blackberry and honeysuckle bushes. Now, the cemetery is managed by the Choctaw Nation and well groomed, and the graves of Tandy Walker and other Choctaw leaders are shaded by massive oaks.

The stagecoach road continued southwest of Spiro, passing near the Skullyville County Jail, the only remaining artifact of the Skullyville County government of the Choctaw Nation. The present stone jail was built in 1888, replacing facilities established soon after the Choctaws were removed to Indian Territory. It is easy to spot from the roadside on Rock Jail Road northwest of Panama.

The county road dead-ends to the southwest, so we detour over Buck Creek Mountain, crossing a steel truss bridge at Brazil Creek. Brazil Station was nearby, a stop on local mail lines, though not an official Butterfield station. Wright observed the station’s old well still in use and a cemetery plot at the site. With property owner Karen Looper, we find the moss-covered gravestones enclosed by a wrought-iron fence, and Looper leads us to the rubble of Brazil School.

Walker’s Station near Skullyville

Turning west on Latham Road toward Trahern’s Station, we come across the second marker near The Ranch at Latham, an event center and performance venue owned by Jonathan and Kelly Watson. The centerpiece of the Watsons’ barn is, appropriately, a stagecoach, and they even have a surrey with a fringe on top. Not surprisingly, cowboy-themed weddings are their specialty.

Trahern’s also was the location of the council house of the Musholatubbee district of the Choctaw Nation. A large mound south of the historical marker is reportedly the grave of Chief Musholatubbee; legend has it the mound is so large because he was buried with his horse.

Beyond the Walls community on Norris Road, we find a real treasure hidden on a hilltop: the only surviving original building along the Butterfield route in Oklahoma. Edwards Store, a hewn-log structure, was built before 1858 and provided stagecoach passengers a good meal, which was a significant luxury on the frontier. A historical marker sits at the roadside. Now unoccupied, the structure appears sound, though its porch is a bit shaky. Two fine stone chimneys still are intact. I walk to the cemetery to gaze north toward the wooded Brazil Creek valley and the hills beyond.

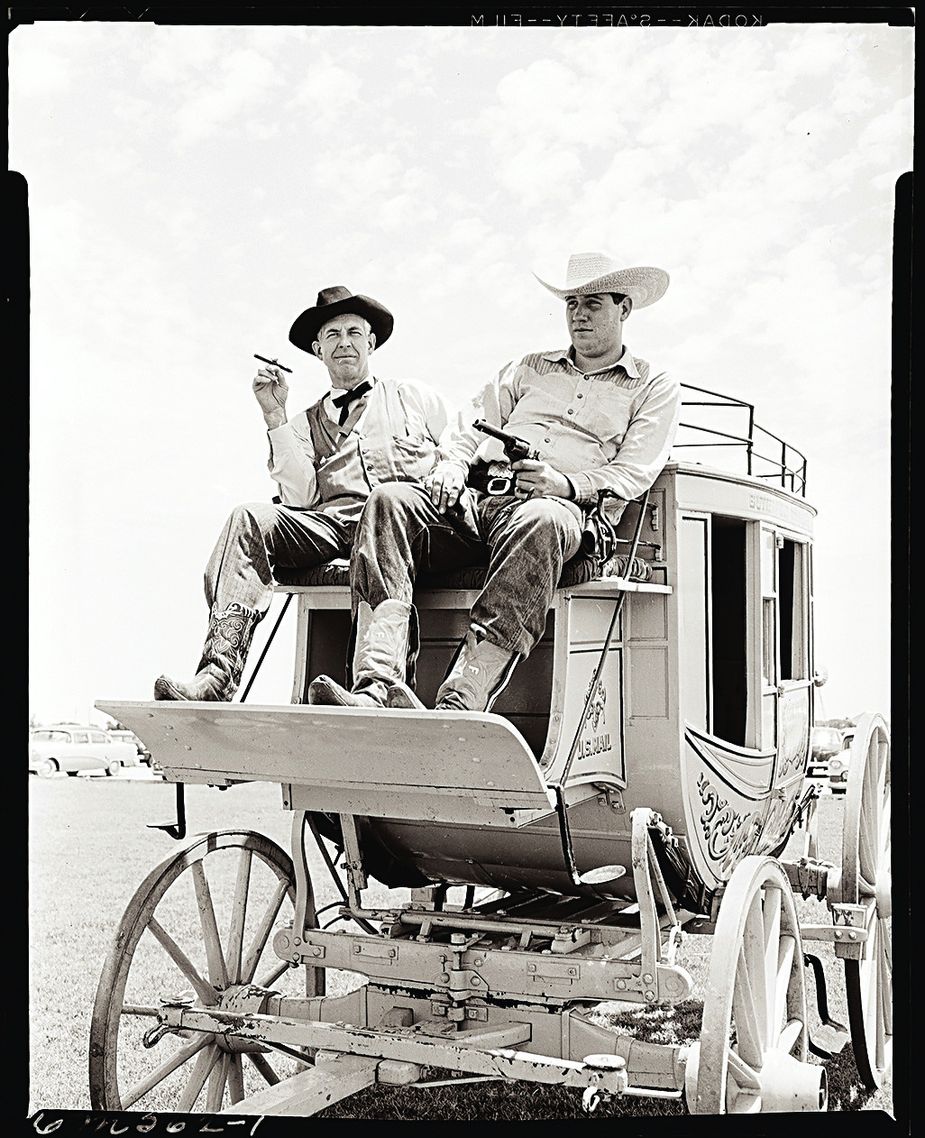

Oklahomans celebrating the Butterfield centennial in 1958

We drive on to Red Oak, stopping briefly at the Holloway’s Station marker, then to the Lutie Cemetery east of Wilburton. The Riddle’s Station marker is located near the cemetery, and the stone-rimmed Riddle burial plot abides near a towering oak.

By this time, we haven’t covered many miles, but it’s taken a lot of time, so we call it a day. Robbers Cave State Park is located among the Sans Bois Mountains a short drive north of Wilburton on Highway 2, and we enjoy a night in one of the cliff-side cabins before hitting the trail again the next morning.

Weddings are a specialty at The Ranch at Latham northwest of Poteau.

From Lutie, the old trail parallels U.S. Highway 270 for about six miles then turns south, ascending to Mountain Station. Now only a cemetery, Mountain Station was not an official Butterfield stop, but it boasted a post office and probably owes its existence to the Butterfield route. For several miles on either side of the cemetery, we can see the depression of the trail within a few feet of the roadway. We stop at a marker for the Mountain Station spring, which still flows. Beyond the spring, we catch a glimpse of a rocky trace of the trail on the hillside.

But the trail is becoming harder to find. An obscure section line road over a low water bridge at Buffalo Creek takes us to Pusley’s Station, where only the base of the historical marker remains. It is right in the trace of the stagecoach road, which leads toward the creek. A fenced cemetery with Pusley family graves appears abandoned. Trees have fallen on the stones, breaking several.

We try to maintain our southwesterly course but encounter a locked gate. This presents an opportunity to venture off the trail to visit Lime Arch Bridge, one of Oklahoma’s few natural stone arches.

Fort Washita near Durant.

To find it, we head southwest out of Hartshorne, eventually turning west on Arch Road. Soon, we spy a small pull-out and a gate clearly intended to provide access for foot traffic and bearing the handwritten words, “Keep gate closed.” A short walk takes us to a huge limestone formation. There, water cascades over a shelf into a pool that flows through a natural arch with an eighteen-foot span. It’s a sight the casual passerby would never suspect.

Reconnecting with the Butterfield trail in Ti Valley, we travel west between limestone hills through a broad prairie. We cross over the Indian Nation Turnpike, and after all the miles of lollygagging along dirt roads, the rapid passage of traffic below is almost a shock. Over the bridge, we take a left on the county road and find the marker for Blackburn’s Station hidden in the weeds along the roadside, its bronze plaque missing.

Turning west, we splash through Brushy Creek at a low crossing and continue along shaded roads to Waddell’s Station. Soon we’re driving in the Atoka Wildlife Management Area and notice a yellow metal sign saying “Butterfield” at a southbound turn-off. The road leads to the ruins of a stage stand at Breadtown Creek. We walk into the woods on a trace of the trail and find a crumbling rock wall and well.

Leaving the Wildlife Management Area, we pop out on U.S. Highway 69 near Stringtown. The back roads we have just driven from Latham wind through some of Oklahoma’s most beautiful mountains and prairies, where settlements are few, and other vehicles are rare. It would have seemed fitting to meet a stagecoach along the way.

Bill Dragoo takes a dinner break at Boggy Depot Park near Atoka, which offers plenty of camping and RV sites.

The next station is Geary’s Stand, which was flooded by the creation of the Atoka Reservoir. A marker stands at the dam, and the wind off the lake emphasizes the drama of our find. Continuing south, we stop at the Atoka Museum and Civil War Cemetery, where the Butterfield trail is memorialized with a large granite marker alongside the graveyard, the only designated Confederate cemetery in Oklahoma.

Boggy Depot Station, a park managed by the Chickasaw Nation, is a good spot for a night’s rest. In 1858, it was the largest and most important settlement on the Butterfield route between Fort Smith and Sherman, Texas. Now, the only evidence of the once-thriving community is the historic cemetery. We camp at the park and have the place nearly to ourselves; an eclectic symphony of cattle, chickens, owls, and coyotes awakens us. Before breakfast, I stroll the dogwood-lined nature trail down to the lake.

From Boggy Depot, the road turns toward the Red River and approaches the Nail’s Crossing Station on the Blue River. It’s inaccessible, but we come close when we stop to visit rancher Jack Risner. His property borders the Blue and also is the site of Fort McCulloch, the main Confederate fortification in southern Indian Territory during the Civil War. Only earthworks remain. We walk the tall man-made mounds with our host then trudge through the river bottom on a trace of the trail to what may have been the Nail’s Crossing, but we can’t tell from the west side.

From Fort McCulloch, the trail runs south to Fisher’s Station, skirts the western edge of Durant, then ends its Oklahoma leg at Colbert’s Ferry. After we find the station marker, we try to reach the actual location of the ferry but encounter a locked gate and a warning sign. The pilings of a toll bridge established later at the ferry site are visible east of the U.S. Highway 69 bridge across the Red River, and we have to be satisfied with that.

One more stop seems necessary to make the trip complete, and, besides, it’s on our way home. Fort Washita, fifteen miles northwest of Durant on State Highway 199, was established in 1842 and during the 1850s was a busy waypoint for travelers headed for the California gold fields. It was supplied via the route we’ve just traveled. It’s a beautiful place now owned and operated by the Chickasaw Nation.

The Butterfield operated for only three years; the outbreak of the Civil War shut it down. But according to Wright, the road was the most important of any in the development and settlement of Oklahoma. The point could be argued among historians, but the Butterfield may well be at once the most well-documented and least changed of any of Oklahoma’s historic trails. Even now, it offers a chance to travel through time.

The Butterfield trail draws today’s traveler close to the past in a way that feels authentic: Sitting on the porch of a log home where stagecoach passengers enjoyed a meal; walking a wagon swale where heavily laden wheels once rolled; cooling off with water from a mountain spring that slaked the thirst of folks riding the long journey to California; and doing it mostly in solitude because of the remoteness of these back roads and relative obscurity of these sites. Much of it is a challenge to find, but therein lies the fun.

Make It Your Trip:

Skullyville Cemetery

Northeast of Spiro on Spring Road.

GPS: 35.25109, -94.59436

The Ranch at Latham

(Trahern’s Station) 30723 Latham Road in Shady Point, (918) 658-4567 or

facebook.com/theranchatlatham

Edwards Store

Norris Road northeast of Red Oak.

GPS: 34.99748, -94.9741

Robbers Cave State Park

State Highway 2 North in Wilburton,

(918) 465-2562 or TravelOK.com/state-parks

Mountain Station

Mountain Station Road southwest of

Wilburton. GPS: 34.83653, -95.42466

Lime Arch Bridge

Four miles east of Blanco on Arch Road

GPS: 34.74958, -95.70216

Atoka Wildlife Management Area

Eleven miles north of Atoka on

U.S. Highway 69, (580) 320-3173 or

wildlifedepartment.com

Atoka Museum and Civil War Cemetery

2902 North U.S. Highway 69,

(580) 889-7192 or

okhistory.org/sites/atokamuseum

Boggy Depot Park

4684 South Park Lane in Atoka,

(580) 889-5625

Fort Washita Historic Site

3348 State Road 199 in Durant,

(580) 924-6502 or chickasaw.net