Mad Songs & Oklahomans: The Tulsa Sound Part One

Published July 2020

By Preston Jones | 31 min read

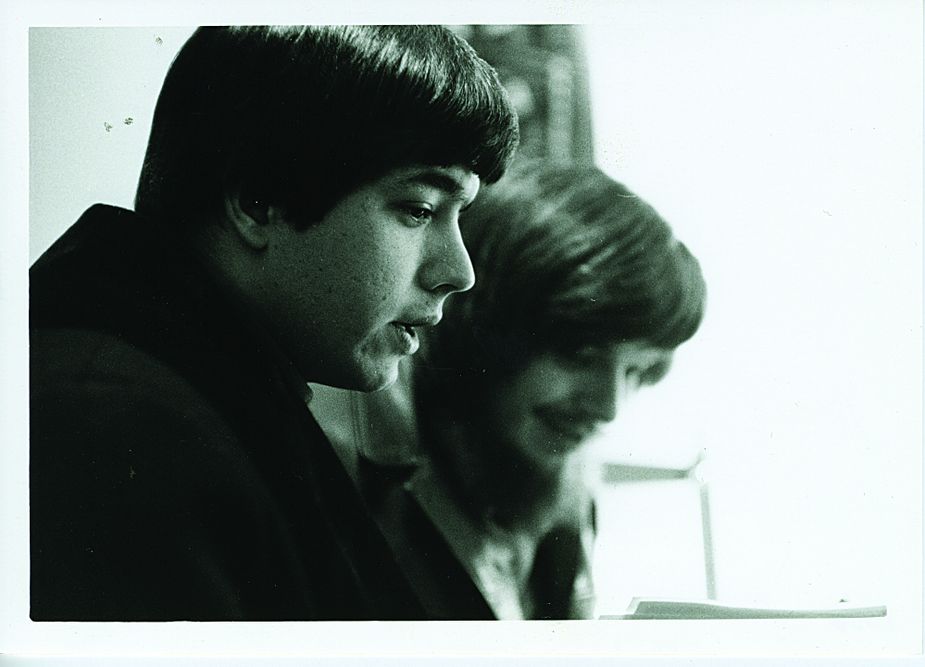

Tulsan Larry Bell, left, collaborated with Leon Russell, right, in California. The late 1950s and early ’60s brought waves of Oklahoma musicians to the West Coast for a time. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

What does Tulsa sound like? Consider the city, for a moment, as the body of a handcrafted acoustic guitar, its gleaming wood overlaid with guitar strings. The individual strings make a sound, but when strummed together, they create a sonic sensation greater than the sum of their parts.

When we consider the so-called Tulsa Sound, it is clearly, indisputably Tulsan. What is less clear is where and when the phrase “Tulsa Sound” originated. Rock critic Robert Christgau, writing in 1981, used it in a capsule review of Eric Clapton’s Backless in his book Rock Albums of the ’70s: A Critical Guide. Closer to home and not long after that, writer John Wooley was likely among the first to cement the phrase in print in his first few years at the Tulsa World.

What is certain is that none of the men to whom the phrase is generally applied—from legendary rock-and-roll impresario Leon Russell to drummer David Teegarden, half of the 1970s band Teegarden & Van Winkle—consider it a distinct musical movement.

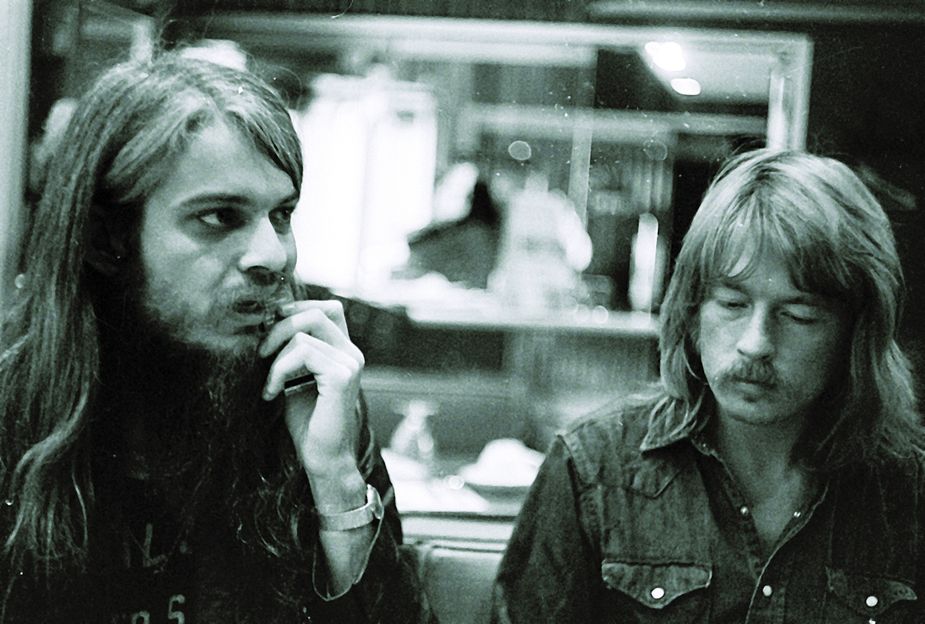

Chuck Blackwell, right, pictured with Leon Russell in the early 1970s, was a major player in the Tulsa music scene. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

“Things happen, and they are what they are,” says Russell. “Writers get hold of them and make up names for them.”

Regardless of when, where, and by whom the term was coined, the Tulsa Sound is a glorious contradiction, a paradox of performance that eludes easy definition. “You know it when you hear it” comes close.

The sound is characterized by a fusion of genres and styles that often make a song feel like it has nowhere in particular to be but is in a slight hurry to get there. There’s a grit to songs like JJ Cale’s “After Midnight,” an intangible roughness around the edges somehow delivered with precision and polish.

In the two-part oral history that follows, Leon Russell speaks to the early, heady days of Tulsa’s music scene, as do Rocky Frisco, David Teegarden, Jamie Oldaker, and Jimmy Markham. All were involved in shaping this distinctive sound of modern-day blues and rock-and-roll. Their recollections evoke a specific place and era—1956 to 1976—and point to the evolution of the city’s rock musicians.

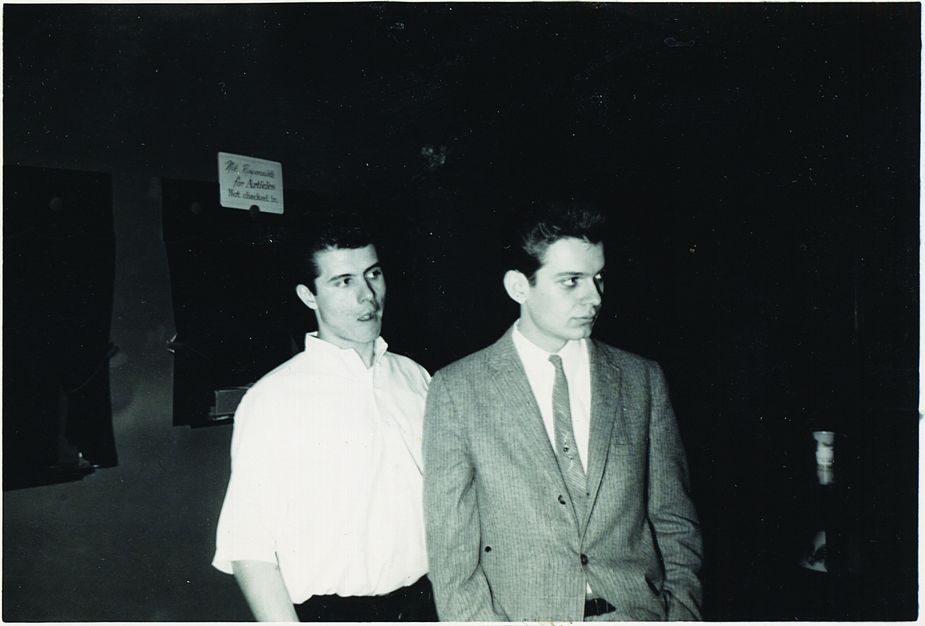

Jimmy Markham and Leon Russell, who at the time used his middle and last name, Russell Bridges, around 1961. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

From its earliest days, the city of Tulsa has enjoyed a rich and varied music culture, but nothing—not even Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, who made history at Cain’s Ballroom and KVOO beginning in 1934—had as much impact as the music that started to emanate from northeastern Oklahoma’s largest city in the mid-1950s. What transpired in Tulsa then was crucial to the development of the singularly American institution that is rock-and-roll. These musicians infused their sound with blues, country, R&B, folk, gospel, western swing, and jazz into a unique brew found nowhere else in the country.

Situated at a musical crossroads between the twang of Texas country and brooding Chicago blues and filtered through its own distinct sensibility, Tulsa birthed a signature sonic style of feeling, texture, and tone that still resonates decades later.

For these artists, music was a fact of life from an early age. Whether it was absorbing the sounds of a vinyl disc or watching country legends perform in ballrooms, every man had his own eureka moment.

Some arrived in Tulsa at birth; others moved from out of state. However they made their way to Tulsa, one thing was clear: Their formative years were full of diverse and important sounds.

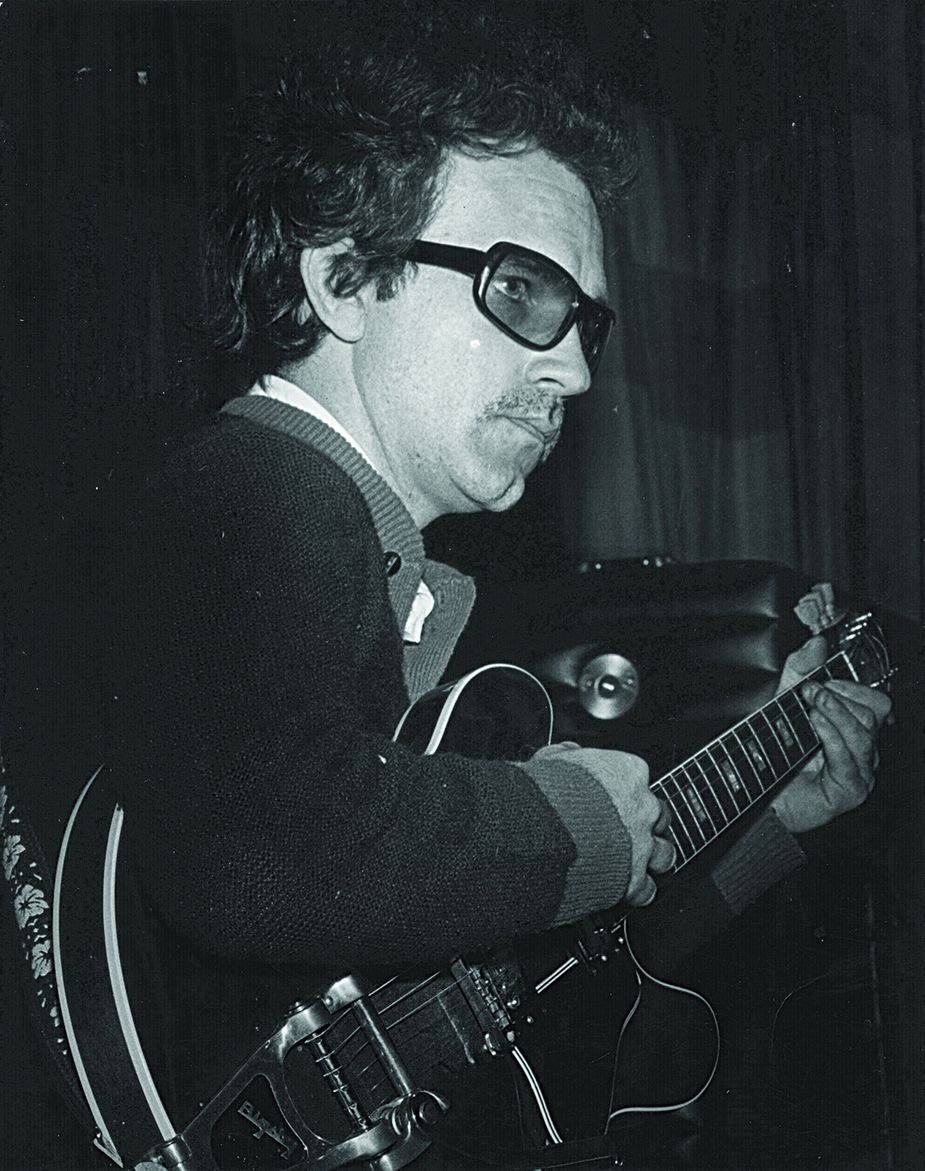

JJ Cale in the mid-1960s. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

Russell: I had amazing impact points when I was first starting. For example, I joined the Columbia House Record Club because it sounded like a good deal. I signed up for the big band [offerings], which I didn’t know anything about, so I got Miles Davis and Benny Goodman, JJ Johnson and Kai Winding, and those kind of acts just because I was on that list. It was quite an education.

Oldaker: I started playing in the school band when I was a kid at Patrick Henry Elementary. My dad played drums, which I didn’t know at the time. I tried out for violin in the sixth grade, but the chairs were full. So I wound up asking if I could play trumpet or trombone: They were shiny—maybe I could get some girls that way. [The band instructor] looked at me and said, “Well, those chairs are full, too. All we have is this.” He handed me a rubber percussion practice pad and a book, so I took them home. My parents asked me, “How was band class?” I said, “All the chairs were full and the band director handed me this.”

Markham: I listened to a lot of early rhythm and blues on the radio. We used to be able to get Wolfman Jack from Del Rio, Texas, on the radio sometimes when everything was in line where we could receive it. There were a couple guys on the radio in Tulsa who played deep blues and R&B music. Seemed like it was once a week, maybe on KRMG radio.

Frisco: We moved to Tulsa in 1940; I was three years old. My mom actually gave me a dollar and sent me down to our neighbor Myrtle’s house at the end of the block to get a piano lesson. I ended up walking out halfway through and told her, “I don’t want to play like this.” She banged my fingers on the piano because she didn’t like the way I was holding my hands. It was raining when I went home. I don’t think a drop hit me, I was so mad. She confessed to me I’d probably never amount to anything.

Now I’m almost seventy-seven and looking back on that day and smiling because I got to play Carnegie Hall with John [JJ Cale], and she probably never played anywhere but her house. There’s more than one way to motivate a little kid.

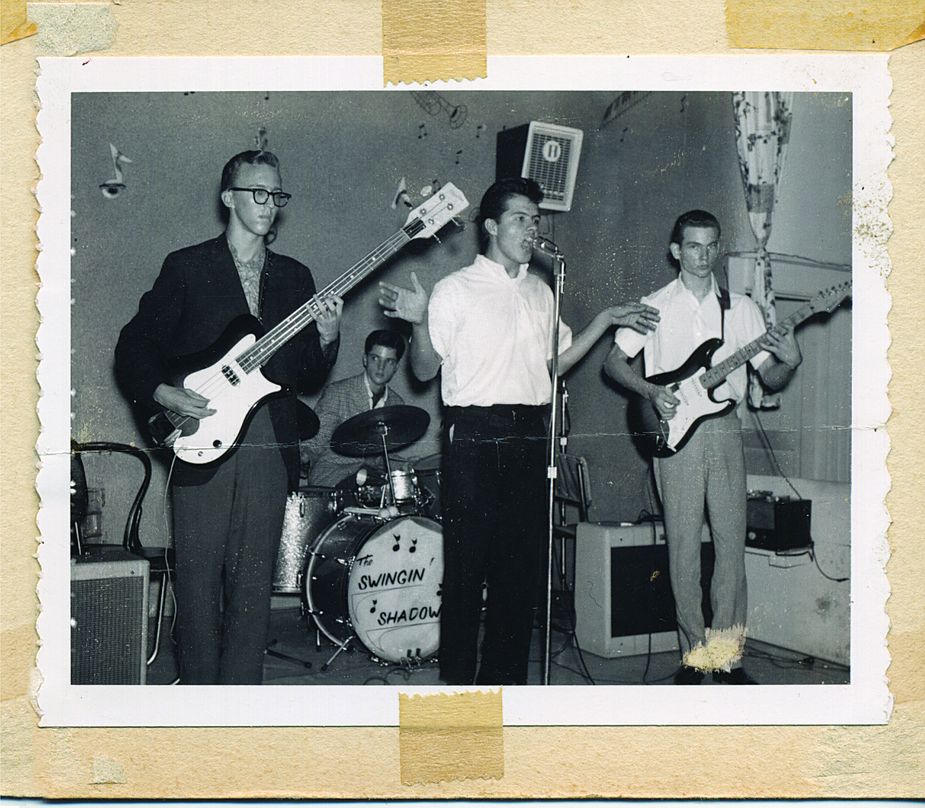

The Swingin’ Shadows, left to right: Carl Radle on bass, Jimmy Karstein, Jimmy Markham, and Tommy Crook performed regularly around Tulsa during the late 1950s and early ’60s. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

Teegarden: It seemed like right out of the womb I was aware of music. My brother Thomas was a trombone player at Central High School and went to TU after that.

My mother was a single parent; my father passed away six months before I was born. My brother was quite a father figure to me. He would pick me up in the afternoon and be talking about music. I remember at a very early age, we were in downtown Tulsa waiting on a bus, standing across from the Philtower building, where a bus pulled up across the street. It was Leon McAuliffe’s bus [McAuliffe was the guitarist for Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys].

They did their afternoon radio show from KVOO and had their studios in that tower for many, many years. I was very much aware there was music going on here.

Cale [from a 2009 KPBS interview]: Early on, when rock-and-roll came in, I was a teenager. I was seventeen years old at that time. Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley—that was, you know, the music of all us teenagers.

So those were the early influences. Then I started playing music. I backed up singers and I just played the guitar; I didn’t sing or anything. I’m a big fan of Mose Allison, a big fan of Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, who are not Top 40 kind of guys.

Russell: The first rock-and-roll shows, in fact, that I saw had twenty, twenty-five-piece bands and fifteen acts on the show. Matter of fact, that Mad Dogs & Englishmen program [Russell oversaw this famous Joe Cocker tour in 1970 that spawned a best-selling album and documentary film] was largely based on those kinds of shows I saw: Lloyd Price and the Biggest Show of Stars, Alan Freed. They had a huge band, and fifteen or more artists would come out and do a couple songs. Substantial artists like Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter, Ruth Brown, and others were on the same show. It was amazing. To me, that was a rock-and-roll show.

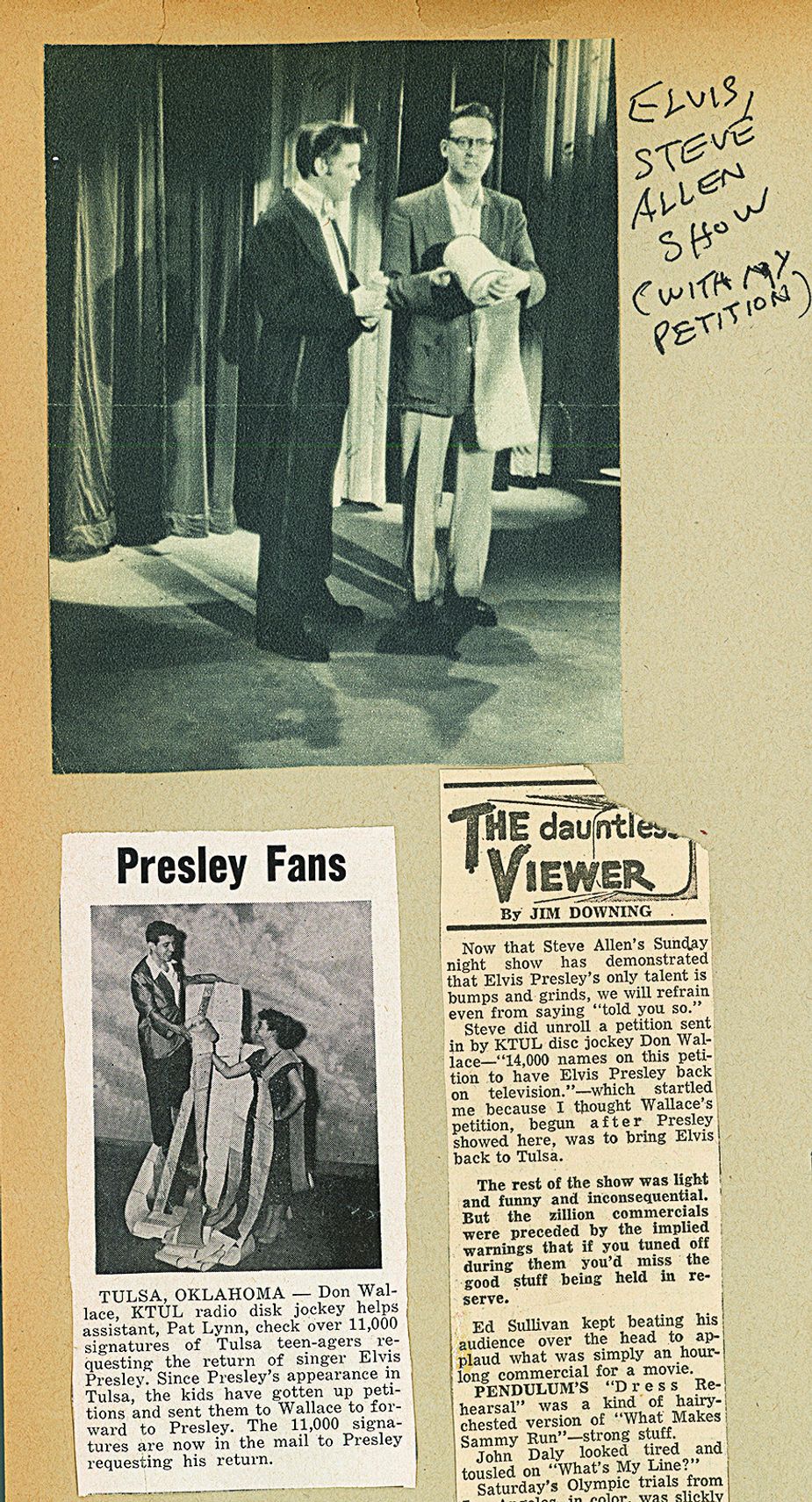

After Elvis Presley performed in Tulsa in 1956, KTUL disc jockey Don Wallace sent him an 11,000-signature petition requesting his return. Photo courtesy OKPOP Museum/Don Wallace Collection

April 18, 1956, was a seminal moment for Tulsa music: Elvis Presley performed a sold-out concert for eight thousand people at the Tulsa Fairgrounds Pavilion.

Of the show, Tulsa World writer David Wood wrote, “The bobby soxers’ dream man, a frenetic twenty-one-year-old singer named Elvis Presley came to Tulsa Wednesday night, and the expected bedlam ensued at the Fairgrounds Pavilion, where thousands of teenagers screamed and panted until they were limp.”

Frisco: Elvis hit the scene, and everything changed. Rock-and-roll was just kind of the blues with a beat.

Teegarden: It was really something to see him in person and see the reaction of all those girls going crazy and screaming.

I liked it; I liked him. It was cool because we got pretty good seats. I noticed the drummer and the bass player. I was impressed he had such a small group; it was just guitar, bass, and drums behind him. It was fun to see that small a group get that much attention.

Markham: That Elvis Presley show turned everything around for me. It was real music; it wasn’t toned down. In those early days, white artists covered black artists, but they were always real sleepy, they weren’t anything like the originals. I think I was listening to records before that, but that [concert] planted the seed in me. I mean, I was a goner after I saw that.

Every local music scene lives and dies by the vitality of its clubs, where talent incubates and intermingles. For hungry young musicians in Tulsa in the late 1950s and early ’60s, gigs were plentiful, whether at places like the Pink Elephant downtown or Griff’s Supper Club on Admiral. The lineups were fluid, the nights were late, and the future legends’ skills were evident early on.

Markham: We started meeting all the people that were in Tulsa, people like David Teegarden and that early crew of us, JJ Cale and a number of other guys.

Bands were formed and introductions were made, and that was the beginning of it. In my first band, JJ Cale was the guitar player; probably Eddie Spraker was in that band. I played my first gig with that lineup. I think I knew four songs, and I just repeated them over and over for three hours.

Frisco: My friend Doug Cunningham was a real, real good piano player. He was Leon Russell-quality before Leon ever showed up.

In fact, the first time I met Leon, Doug brought him to one of the dances at the YMCA. Leon was a little guy; he was about fourteen then. Doug told me: “This kid has already had seven years’ classical training; he plays piano better than I do.” I couldn’t believe it.

Teegarden: I just locked onto Cale; he was like a big brother to me.

Oldaker: I started playing around Tulsa with Dick Sims and some people I went to school with. I was in a band called Mike and the Cavaliers when I was about twelve, I guess. They were all older than me. I used to have to stand on a box to get my picture taken, I was so short.

What was bubbling up in the dance halls, school socials, and nightclubs began to spill over the state’s borders in 1957, with the release of Clyde Stacy’s “So Young,” a song that would eventually reach number 68 on the Billboard pop charts. Stacy moved to Pennsylvania in 1958, where he would record and tour, off and on, until 1963.

Frisco: I got a call from Clyde—he was living up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He wanted me to come up and form a band for him with local musicians, because I had the piano signals he needed. Clyde retired from The Harmony Flames; he married this real pretty blonde named Evelyn and went to work for his uncle [in Oklahoma] who had a fence company. I took over the band [in Pennsylvania], and that’s where the band Rocky Curtiss and the Harmony Flames came from.

We toured for a couple years, did really well, got some good reviews, and then I retired from the band. I made that album for Columbia [1959’s The Big Ten], and the A&R guy I had trusted embezzled $45,000 out of my Columbia account, and then he died. I was so pissed off, I said, “I’m not going to do this anymore.”

Having performed in Tulsa clubs since age fourteen, Russell decamped for Los Angeles in 1958, but his original attraction to the West Coast wasn’t strictly musical. A steady stream of Oklahomans would follow him.

Russell: I went to Los Angeles to get in the advertising business. When I got out there, I found out it was quite a bloody business. They really hurt my feelings a couple times, and then I started playing on records. I didn’t really go out there for music.

When advertising didn’t work out, Russell turned to the music business. He began recording on his own and eventually became an A-list session musician, contributing to an array of classic records, including singles from Sam Cooke, Johnny Mathis, and a number of Phil Spector-produced projects, including “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” (1963) and “Be My Baby” (1964).

Markham: You used to could throw a rock and not help hitting an Okie, because all of us were cozied up there [in LA]. It felt like it did at home, because all the guys were there. Leon had gone pretty early on, previous to a lot of us. He had played nightclubs there for a long time.

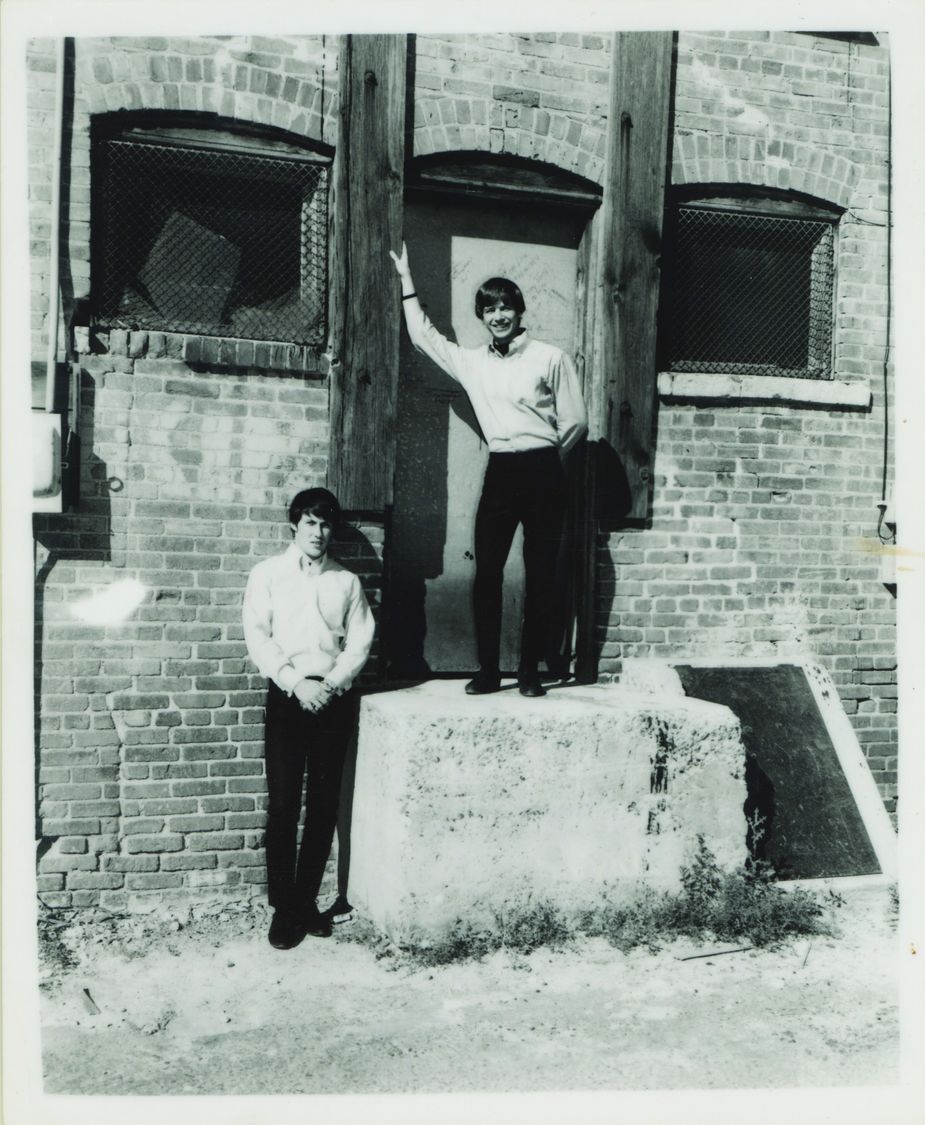

Before their musical act became known as Teegarden & Van Winkle, Skip “Van Winkle” Knape and David Teegarden performed as the Sunday Servants. Photo courtesy David Teegarden Collection

Teegarden: When I moved out to LA [around 1964-65] to live at Leon’s house, Cale was coming up there every day to record. Leon opened the doors for Cale—they were all buddies. I assisted Cale almost every day at Leon’s house, where he had a real nice studio. I wasn’t there that long, but so much happened in that space of time.

The album perhaps most responsible for initially showcasing the abilities of Tulsa talent to an international audience is British singer-songwriter Joe Cocker’s seminal 1970 live record Mad Dogs & Englishmen, captured at New York City’s Fillmore East during the hastily assembled tour of the same name.

Russell, whose single “Delta Lady” Cocker had covered on his 1969 self-titled album, oversaw the seven-week tour, which featured a murderer’s row of Tulsa talent: Carl Radle, Chuck Blackwell, Jim Keltner, and Russell himself backing Cocker.

Russell: I went to the [1971] opening of the [Mad Dogs & Englishmen] movie in London, and it was in a theater that held three thousand people. When I walked in with the crowd, nobody saw me.

I walked out after the movie, and there were three thousand pairs of eyes on me. I was not surprised at the impact that movie had. Moving media is a lot stronger than playing for a couple hundred people. Movies always make a bigger impact than the stuff that’s recorded.

Teegarden: I can’t even describe how fulfilling it was [seeing the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour]. To me, it was major. I thought it was amazing that Leon really knew how to put all that stuff together to make it happen. Leon was a masterful arranger; he told everybody what parts they were supposed to play.

Russell: I feel like when we were actually doing the Mad Dogs tour, which didn’t last very long, I would’ve said that it had a marginal impact at that time. Here and there, some nights were better than others. After the movie had been around forever—it’s like wine, I guess. It gets better with time.

Fresh from the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour and his burgeoning solo career, Russell moved back to Tulsa in 1972 and shook things up in a big way, opening the Church Recording Studio at Third and Trenton.

Having launched Shelter Records in 1970, Russell became a magnet for rock royalty, many of whom—like George Harrison, Tom Petty, and Elton John—came to Tulsa to record or simply hang out and soak up the vibes.

Oldaker: Once Leon put that studio in, there was music going on on every side of town. It was pretty cool, because there were great bands all over the place. You could go to any part of town and always hear somebody good.

One musician who spent a lot of time in Tulsa during this period was Eric Clapton, who will, in the second half of this recounting, bring Tulsa musicians including Oldaker, his friend Dick Sims, and Carl Radle to Miami’s Criteria Studios, where they’ll record one of the most influential records of the 1970s, 461 Ocean Boulevard.

Left to right: Jimmy Karstein, Atlee Yaeger, Gypsy Boots, Jimmy Markham, and JJ Cale at the Hollywood Palladium in 1965. Photo courtesy OHS/OKPOP Museum Collections

The Players

At the center of the Tulsa Sound are these talented musicians.

Chuck Blackwell (1940-2017) Drummer. Key albums: Mad Dogs & Englishmen, Carney

JJ Cale (1938-2013) Vocalist, guitarist, songwriter, and producer. Key albums: Troubadour, Okie, Roll On

Gene Crose (1936-) Vocalist and songwriter

Rocky Frisco (1937-2015) Vocalist, pianist, and songwriter. Key album: The Big Ten

David Gates (1940-) Vocalist, songwriter, guitarist, producer, and lead singer of Bread. Key album: Baby, I’m-a Want You

Jimmy Karstein (1943-) Drummer. Key albums: Last Time Around, Home, The Tractors

Jim Keltner (1942-) Drummer. Key albums: Walls and Bridges, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, A Momentary Lapse of Reason

Jimmy Markham (1941-2018) Vocalist and harmonica player. Key albums: To Tulsa and Back, Asylum Choir II

Jamie Oldaker (1951-2020) Drummer, producer, and arranger. Key albums: Slowhand, Mad Dogs & Okies

Carl Radle (1942-1980) Bassist. Key albums: Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, Slowhand

Bill Raffensberger (1941-2010) Bassist. Key album: Roll On

Leon Russell (1942-2016) Pianist, composer, producer, and arranger. Key albums: Leon Russell, Carney, The Union

Dick Sims (1951-2011) Keyboardist. Key albums: Slowhand, 461 Ocean Boulevard

Clyde Stacy (1936-2013) Vocalist and guitarist. Key recordings: “So Young”/“Hoy Hoy”

David Teegarden (1945-) Drummer, vocalist, and producer. Key albums: An Evening at Home, Nine Tonight

Verbie Gene “Flash” Terry (1934-2004) Vocalist and guitarist. Key recordings: “Cool It”/“Her Name Is Lou”

Charlie Wilson (1953-) Vocalist and songwriter for The Gap Band. Key albums: The Gap Band III, Gap Band IV

Robert Wilson (1957–2010) Bassist for The Gap Band

Ronnie Wilson (ca. 1949-) Songwriter and keyboardist for The Gap Band

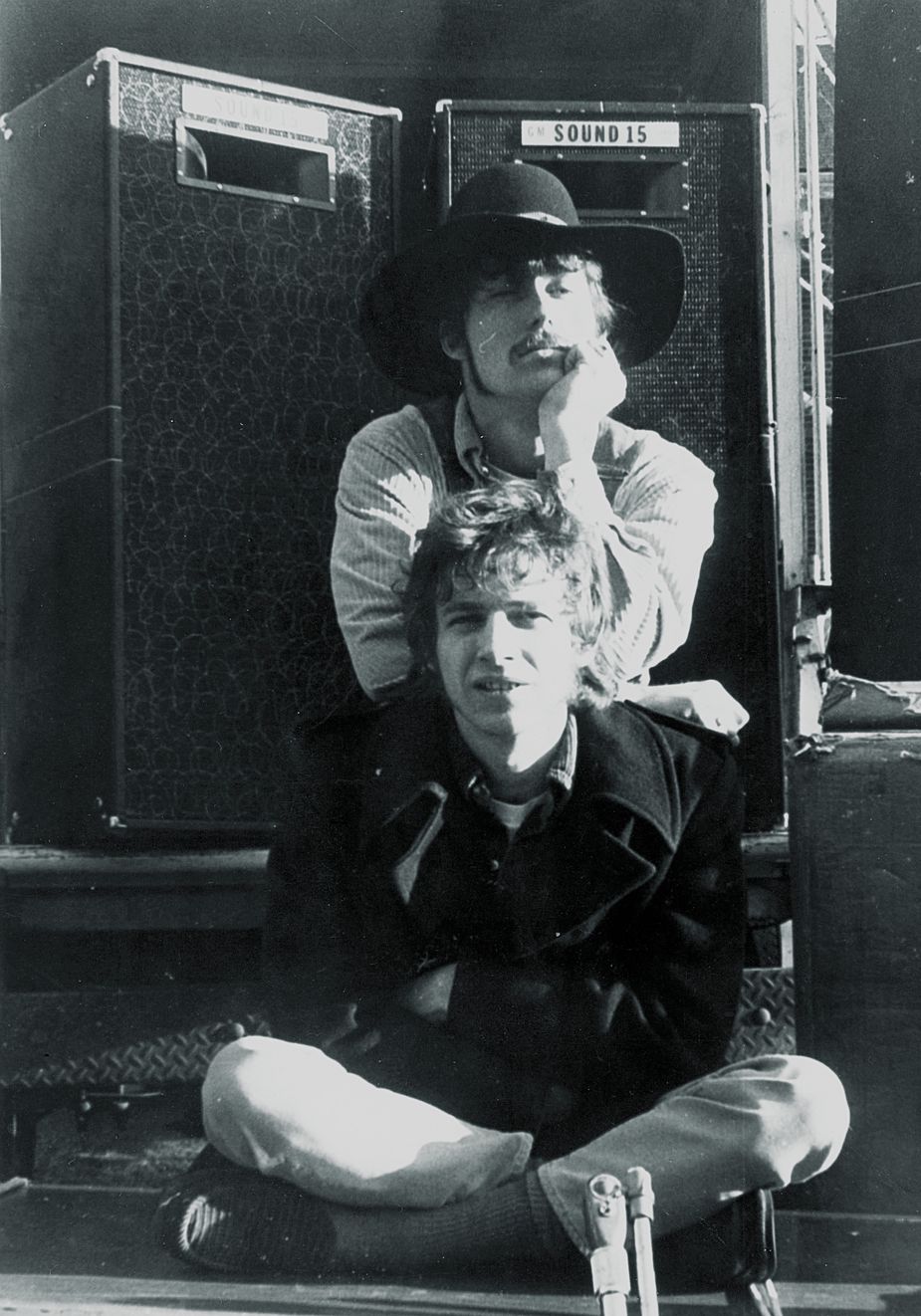

Teegarden & Van Winkle, shown here in Detroit in 1968, made the Billboard Hot 100 chart with their 1970 single “God, Love, and Rock & Roll.” Photo courtesy David Teegarden Collection

The Spin

The Tulsa Sound must be heard to be fully understood. These ten essential tracks represent either an introduction to or a reminder of one of Oklahoma’s most revered musical eras.

“Hoy Hoy,” Clyde Stacy (1957)

This perspiring blend of rockabilly and lustful lyrics—“My baby’s kisses taste like cherry pie”—was recorded at Tulsa’s Oral Roberts University and eventually landed on the Billboard Top 100. Stacy’s seminal first single is the sound of something influential coalescing for the first time. Its flip side, “So Young,” also did well on the charts.

“I Told Myself a Lie,” Rocky Curtiss and the Harmony Flames (1959)

Tulsa-bred singer-songwriter Rocky Frisco, performing under his stage name, Rocky Curtiss, slows rockabilly’s nervous energy down to half-speed for this spiky ballad taken from his one and only major-label release, 1959’s The Big Ten. Don’t miss Teo Macero’s restless saxophone dueling with Pete DeMarzo’s cascading guitar lines behind Frisco’s plaintive vocals.

“She’s My Baby,” Flash Terry (1961)

Listening to this supreme slice of blues, it’s almost possible to detect smoke in the air of a juke joint on Tulsa’s north side in the late ’50s or early ’60s. Almost every musician who grew up in that era of Tulsa music credits the late Terry with being one of the bedrock components of Tulsa’s distinctive musical style.

“Black Cherry,” Junior Markham & the Tulsa Review (1968)

Produced by JJ Cale, this single and its flip side were cut after Markham’s sojourn to Los Angeles. With a relentless blues-soul groove and Markham’s go-for-broke vocal performance, “Black Cherry” kicks like little else that came out of Tulsa, a reminder that the blues, seductive though they may be, also pack plenty of heat.

“Delta Lady,” Joe Cocker (1969)

This song appeared on Leon Russell’s self-titled debut, which also spawned the hit “A Song for You.” Cocker’s version hit the market a year before Russell’s. However, it was Cocker’s incendiary live version in the 1971 Mad Dogs & Englishmen documentary that would forever sear the song into the culture’s collective memory.

“God, Love, and Rock & Roll,” Teegarden & Van Winkle (1970)

The duo of drummer David Teegarden and singer-songwriter Skip Knape (also known as Skip Van Winkle) admit that this gently psychedelic hit (which made it all the way to number 22 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart) borrows heavily from the Jester Hairston hit “Amen,” but the Tulsa duo found a style all their own, laying an easy groove against a soulful choir for heavenly results.

“After Midnight,” JJ Cale (1971)

Those only familiar with Eric Clapton’s 1970 hit cover of this Cale classic might be surprised by the smoky, understated feel of the songwriter’s version. While it’s tough to single out one element that makes this track distinctly Tulsan, it is by far the clearest example of what became known as “that Tulsa thing” on record.

“Tight Rope,” Leon Russell (1972)

The opening track for Russell’s breakthrough third solo album, Carney, this quirky hit ultimately reached number 11 on the Billboard Top 100 charts. It is a textured fusion of stride piano, a loping backbeat (courtesy of Chuck Blackwell and Jim Keltner), circus imagery, and Russell’s inimitable vocals, creating a pocket of peculiarity amid his fellow Tulsa musicians.

“Cocaine,” Eric Clapton (1977)

Less than a year elapsed between the release of JJ Cale’s rendition (on his 1976 album Troubadour) and Clapton’s enduring cover of the infamous tune. The syrupy, almost swampy guitar riff is present in both versions, but it was Clapton’s slightly faster, more polished rendition that shined a spotlight on the Tulsa sensibility.

“Baby Likes to Rock It,” The Tractors (1994)

Drummer/producer Jamie Oldaker is one of the founding members of this seminal Oklahoma country act, and you can hear him keeping time as only he can on this funky, shuffling hit from The Tractors’ self-titled debut. The tune made it to number 11 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart.