Girl Hero

Published July 2022

By Graham Lee Brewer | 14 min read

I don’t care what’s right or wrong / and I won’t try to understand / Let the devil take tomorrow / But tonight I need a friend.

When Sammi Smith sang those words in 1970—the unforgettable lyrics to Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night”—it changed country music forever. The five-foot blonde spitfire from Guymon had a voice that dripped with soul, but it was what she said—not just how she said it—that would make her a country star and cause Waylon Jennings to give her the nickname “Girl Hero.”

Sammi Smith, born Jewel Faye Smith and raised in Guymon, paused to pose for this photo in between takes during a television appearance taping.

Starting in the late 1960s and continuing into the ’80s, Smith would go from a child bride with three children, to a twenty-something divorcée singing in Oklahoma City bars, to one of the biggest country singers of her time, to an Oklahoma rancher far removed from the airwaves and the bright lights.

Now, nearly fifteen years after her death, Smith’s name rarely is invoked save for the outlaw country fans and locals left who remember her smoky voice. Yet in a time when women are asserting their rightful place in the entertainment industry more than ever, it hardly seems fair that a trailblazer, a woman who took risks and climbed so high, is all but forgotten in popular culture. Because the biggest risk Sammi Smith ever took—as the first of many to give voice to Kristofferson’s unforgettable song—had a lasting impact for women across the country.

.jpg)

Smith counted country legends like Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, and Willie Nelson, here on stage in 1973, as lifelong friends. Photo by Ron McKeown

But before any of that, Jewel Faye Smith was a teenager growing up with her father, a house painter and day laborer, in Guymon. In her teens, Smith married a steel guitar player named Bobby White. The couple had three children, one right after the other, when Smith was still a teenager herself, says her longtime friend Dee Rominoff. The couple divorced in 1966, and Smith moved to Oklahoma City to work the music clubs, trying to make it as a singer.

“If Sam was singing, she was happy,” says Rominoff, now a Dallas resident. “When she sings, you can hear it. It was a release for her.”

Smith was trying to put a difficult marriage behind her, break into a tough industry for women, and learn how to be independent all at once, says her son, musician and actor Waylon Payne.

Smith with fellow country musician Vince Matthews. Photo by MF Andrews

“She told me she didn’t know how to be a lady very much,” Payne says. “There were some drag queens living in the hotel she was living in that taught her how to do her hair and makeup.”

In fact, it was the infamous Oklahoma City drag queen Ginger Lamar who first showed a young Smith how to dye her hair blonde, which would become a staple of her image. But underneath that golden crown of hair was a woman ready to hustle. Marshall Grant, bassist for Johnny Cash, saw Smith singing at an Oklahoma City nightclub and spoke about her to his boss.

This was the break Smith had been working for, and soon, she moved to Nashville to begin her career. She had some hits in the late ’60s, starting with “So Long Charlie Brown, Don’t Look for Me Around” in 1967. But it was her 1970 cover of “Help Me Make It Through the Night” that rocketed her to fame, catapulting Kristofferson to songwriting success and giving her a major break.

“Sammi, I remember five or six years ago, when Luther Perkins was alive and how he and Marshall Grant talked about Sammi Smith and what a great talent she was, and then I met you and heard you sing, then we all became friends,” Cash wrote to her from his home in Hendersonville, Tennessee, in 1972, when she was at the height of her success. “I don’t know if I said so back then, but I always knew that the whole world would someday hear your voice.”

Smith performed at Willie Nelson’s first 4th of July Picnic in Austin in 1973. Photo by MF Andrews

When Smith sang Kristofferson’s song about a man asking a woman to come keep him company at night, she reversed the gender roles, which, gauged by the restrictive cultural standards of the time, was an enormous risk.

“Come and lay down by my side / ’Til the early mornin’ light / All I’m takin’ is your time,” she sang. “Help me make it through the night.”

For country music fans at the time, hearing such lyrics from a female singer was shocking.

“It was the first time on radio that a woman sang, ‘I want to sleep with you, I’m making my choices, I’m making my own decisions,’” Payne says. “It was the first time on country radio that a woman spoke about her own needs. It was groundbreaking.”

The song ignited a scandal in the music industry, especially at country stations in 1971 rural America. Payne says many refused to play it, and she was called a whore by some churches. Nevertheless, she won a Grammy for Best Country Vocal Performance by a Female in 1972, and the song remained at number one for three weeks. Smith’s career was buoyed by the strength of that hit for another two decades. Payne recalls summers on the road with his mom, singing at rodeos with her backing band Apache Spirit and sleeping on the side of the road in her gold Mercedes, her .38 pistol in her lap. She finally had achieved a long-sought-after success.

“Every truck stop we stopped at, ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’ was always on the jukebox,” he says. “It was a big, big, big thing for her.”

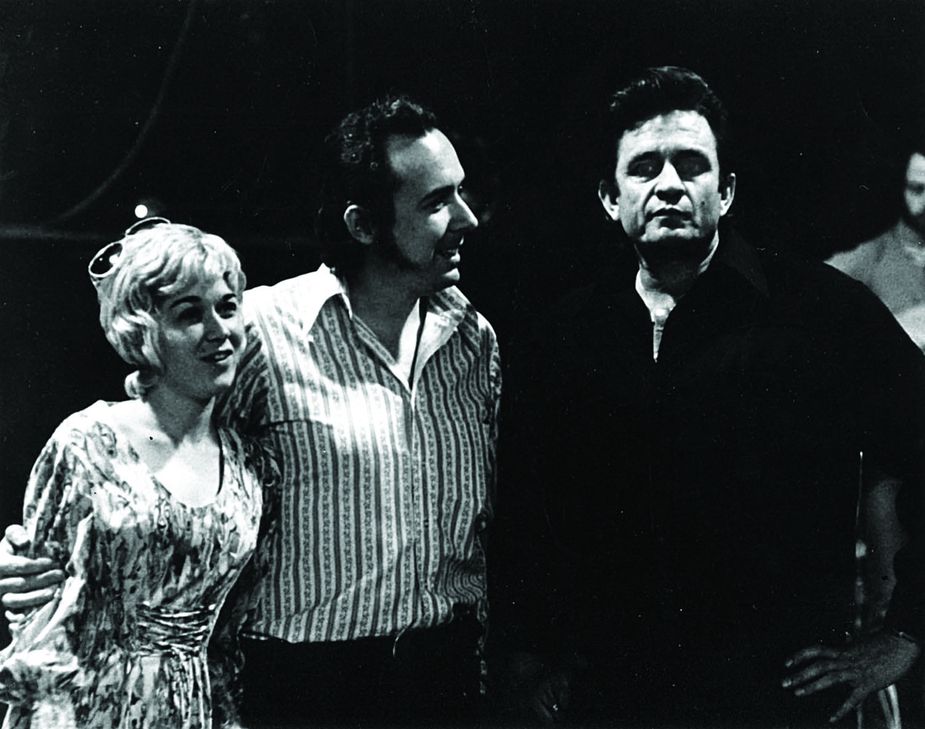

Smith with Jim Ed Brown and Johnny Cash.

Despite the fact that Smith’s male country music peers were singing about drinking, drugging, and womanizing, women in the industry were expected to be ladylike. Smith bucked that notion both on- and offstage. She had a reputation as a prankster who did and said what she wanted, not necessarily what society expected of her.

“She was fearless in the songs that she picked and the things that she would do,” says Ray Wylie Hubbard, another icon of the outlaw movement.

Outlaw country is known as brash, even rowdy, and it came about in an effort to counter traditional notions of what country music should be. Outlaw musicians wanted to play the honky tonks, sure, but they also wanted to play for the hippies in Austin and Los Angeles. While Smith’s soulful vocals and harmonies didn’t always fall neatly into the emerging genre, as a performer and as a woman, she was a perfect fit.

“The whole kind of outlaw thing was actually these guys not being dictated what they should sing, they were just doing it,” Hubbard says.

Smith with Willie Nelson and University of Texas football coach Darrell Royal. Smith’s son Waylon Payne says it is his favorite photo of her. Photo by MF Andrews

Hubbard describes Smith as both a mesmerizing performer and “a great hang,” noting how comfortable and confident she was in any setting, whether that be a country club or a hippie get-together.

“We’d play these old funky clubs, and she would come out and be one of the guys, except she was beautiful,” Hubbard says with a laugh.

Some described Smith as running with the men, but those who knew her well argue the men were keeping up with her just as much as the other way around. If anything, the controversy around “Help Me Make It Through the Night” embodied that.

“Up until that point in country radio, woman were always gingham-wearing, stand-by-your-man,” Payne says. “That was not the way with that song, and it totally changed the way that women were able to sing songs.”

Smith felt stifled in Nashville, where traditional country aesthetics often were pushed on her by the industry. Her independence was not considered an asset.

“She just wanted to be a soul singer,” says Rominoff.

Oklahoma City artist Cassie Stover created this portrait of Sammi Smith for Oklahoma Today using acrylic and spray paint.

But that side of her talent was overlooked in country music’s capital, says Payne, where record label reps wanted Smith to fit a more traditional mold. He says listening to his mother’s original, unused recordings, it was clear to him that she wanted to sing soul, and the outlaw country movement offered her an opportunity to set her own rules.

Smith left for Dallas about a year after her Grammy win to join outlaw musicians like Cash and Willie Nelson. It was there she met her second husband, Jody Payne, Nelson’s guitar player. Smith continued to record hits like “Kentucky,” “Today I Started Loving You Again,” and “What a Lie,” but nothing matched the runaway success of “Help Me Make It Through the Night.”

Smith’s star began to fade in the late ’70s, when country music shifted toward a pop-oriented sound, a perennial trend that would repeat itself a couple more times in the coming decades. Smith withdrew from the spotlight, choosing instead to settle down with her third husband, Johnny Johnson, on their ranch in Bristow, where she pursued one of her other passions: horseback riding. She died of emphysema in 2005 in Oklahoma City and was buried in her hometown of Guymon. Jennings’ nickname for her, “Girl Hero,” adorns her gravestone. For those who knew and loved the woman and her music, however, she lives on.

“That’s what I’m afraid of, that she’ll just become a ghost,” says Payne, who hopes to publish some of his mother’s unreleased recordings and remind people why she is such a vital part of history. “She was just too important to country music.”

Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame

Sammi Smith is honored in the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame, 401 South Third Street in Muskogee, (918) 687-0800 or omhof.com.

Elmhurst Cemetery

Sammi Smith is buried at Elmhurst Cemetery in Guymon. U.S. Highway 54 and Memory Lane, (580) 338-3396 or guymonok.org.