Freedom Road

Published February 2021

By Quraysh Ali Lansana | 25 min read

By Quraysh Ali Lansana with research by Bracken Klar

Portraits by Shannon Nicole

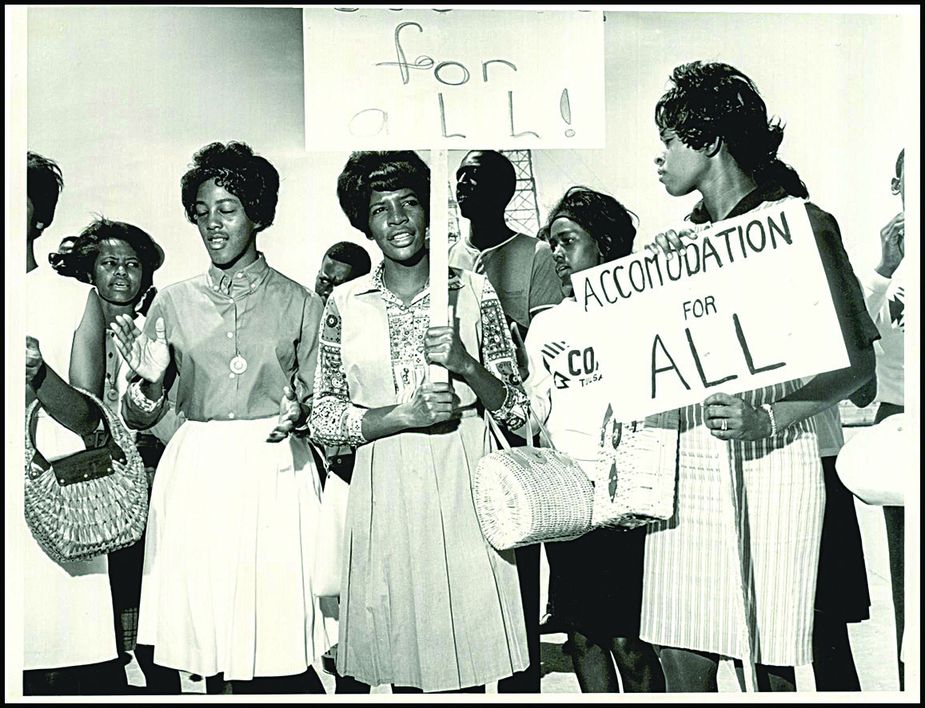

Civil rights protesters marched at the Oklahoma State Capitol on June 7, 1964. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

The 1960s generally are considered the heart of the modern struggle for African American civil rights, and many of that era’s most well-known moments happened in the Deep South. But Oklahoma’s place in the Civil Rights Movement is important and unique. The state’s red earth served as battleground and litmus test for the movement dating all the way back to before statehood. Though great progress has been achieved here, many of those old growing pains continue to ache.

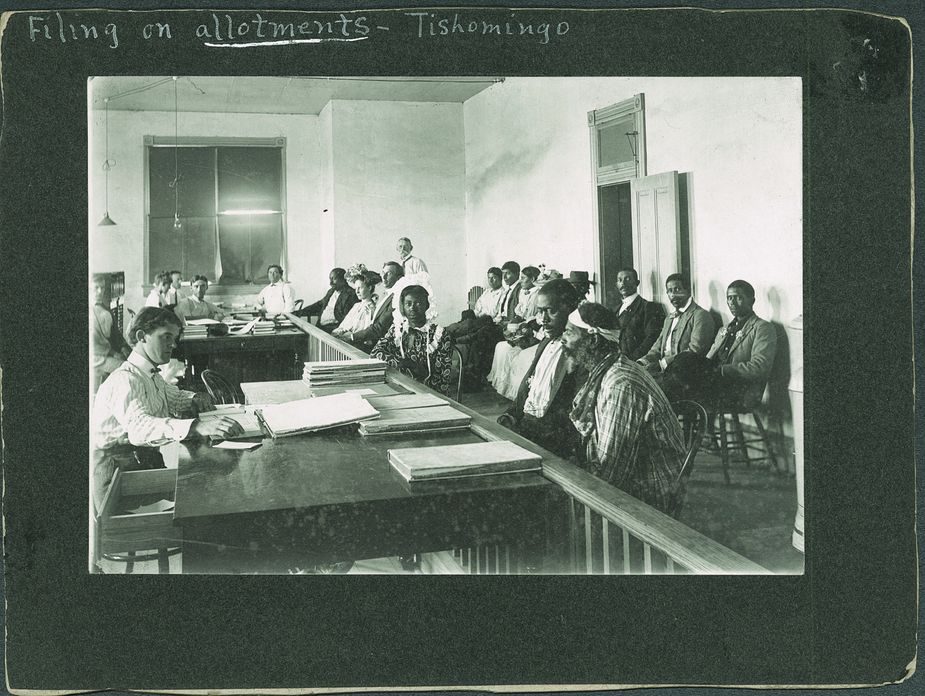

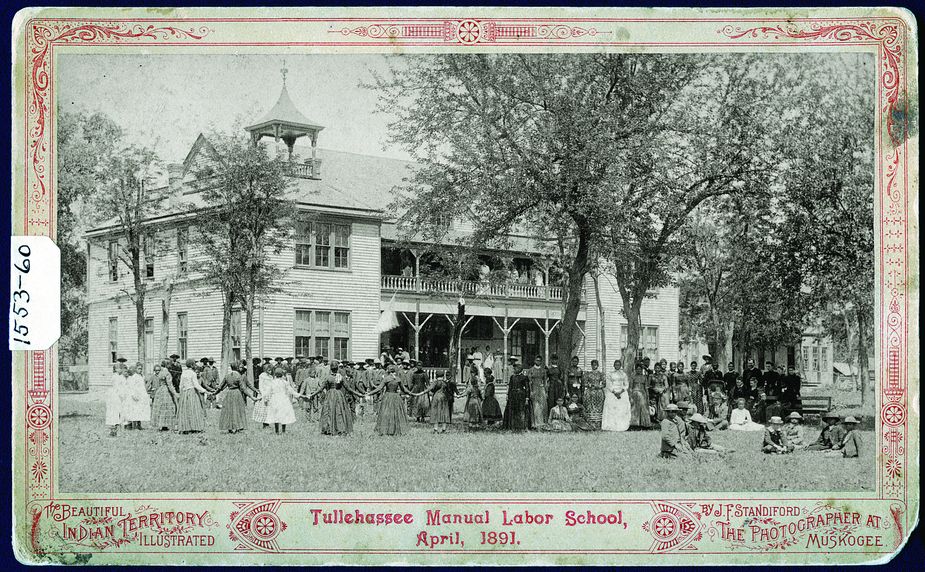

Most Blacks initially arrived in Indian Territory in the middle of the nineteenth century via the Trail of Tears and other forced relocations as the property of the slaveholding Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Seminole nations. Many attempted to escape their bondage by revolt or by running away, and both black and white abolitionists worked to overturn slavery during this time. By the 1861 onset of the Civil War, these tribes owned approximately 10,000 Africans. After the war, the federal government granted freedom and allotments of land to newly freed black citizens, an initiative that was not greeted warmly by all Native Americans.

“Following the Civil War, these slaves were freed and entered into the tribal life of the Indians, intermarrying and becoming an integral part of the Red Man’s life and customs,” wrote Roscoe Dunjee, editor of The Black Dispatch newspaper in Oklahoma City, in an editorial dated April 29, 1939.

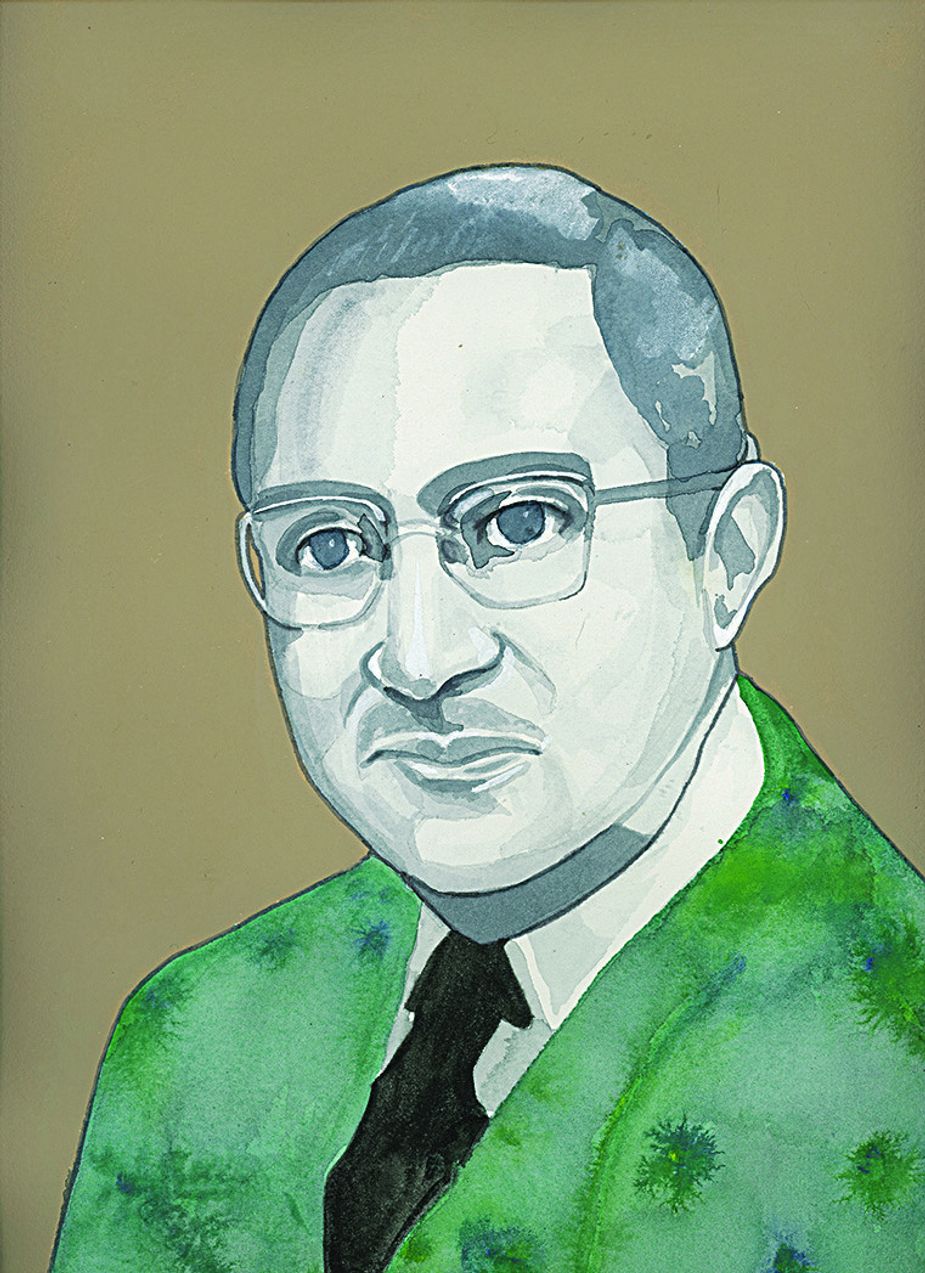

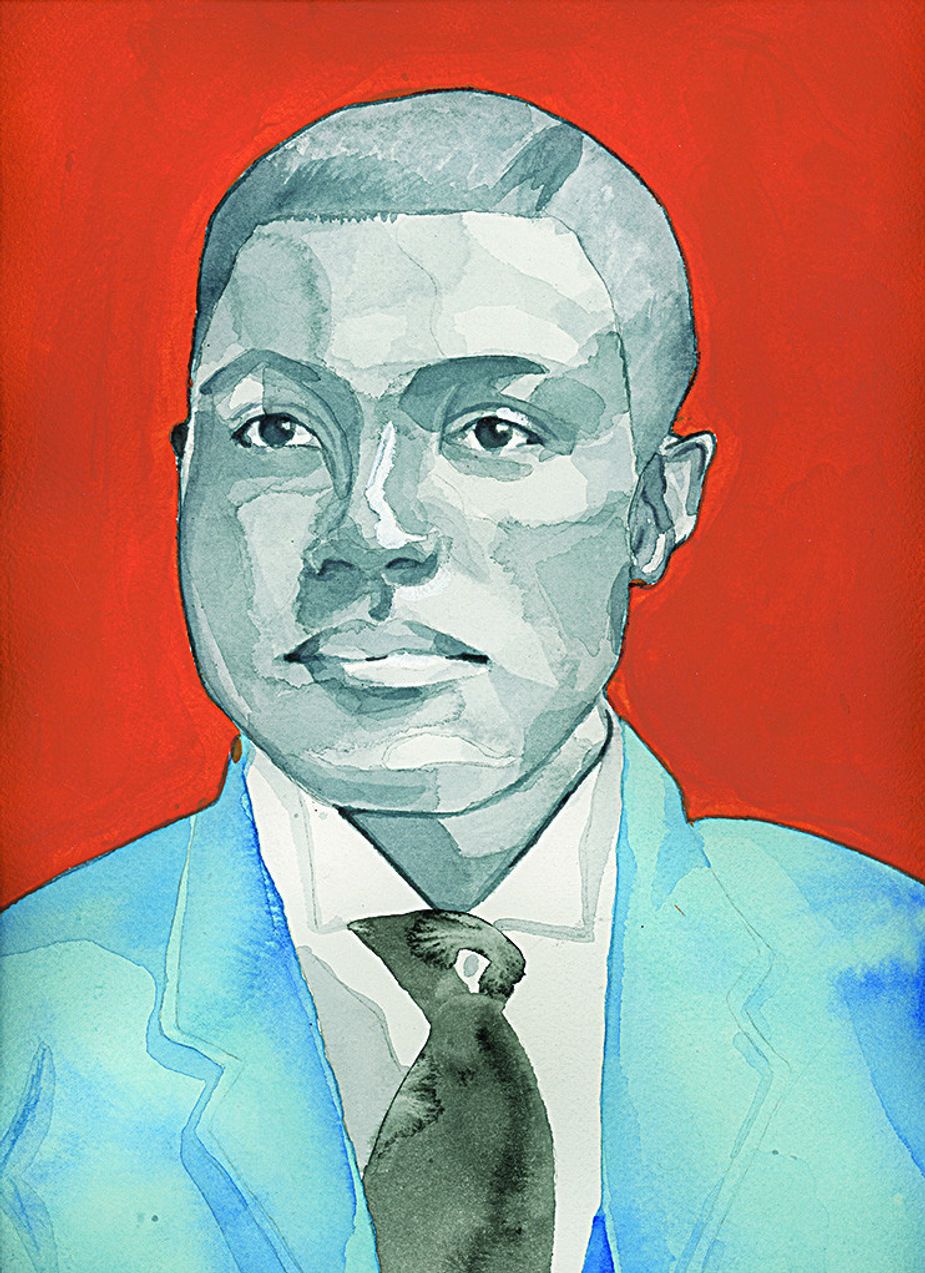

The Black Dispatch founder Roscoe Dunjee. Portrait by Shannon Nicole

These former slaves, known as Freedmen, attained significant economic and political gains amid great indifference from both Native Americans and whites. No longer property but property owners, the Freedmen cultivated farms and livestock in addition to becoming entrepreneurs and merchants. Some white people resented the wealth and stability black Oklahomans acquired during the period, and their hatred often manifested in threats and lynching bees. Many Native Americans, also struggling to sustain their own independent economy, treated the Freedmen with disdain. But their success paved the way for a second migration of African Americans into the land that would become Oklahoma.

It was the promise of land that spurred this second migration, beginning with the first Land Run in 1889. During the 1880s, it had been the task of Henry O. Flipper, the first black graduate of West Point, and Allen Allensworth, a black chaplain—they were the only black commissioned officers to serve in the territory—to lead the Twenty-fourth Infantry in their task of preventing “Sooners” from illegally relocating from Kansas to Oklahoma. Clashes between the all-black Twenty-fourth Infantry and the mostly white “Soomers” negatively affected race relations in the state for decades.

Chickasaw Freedmen file for allotments in Tishomingo. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

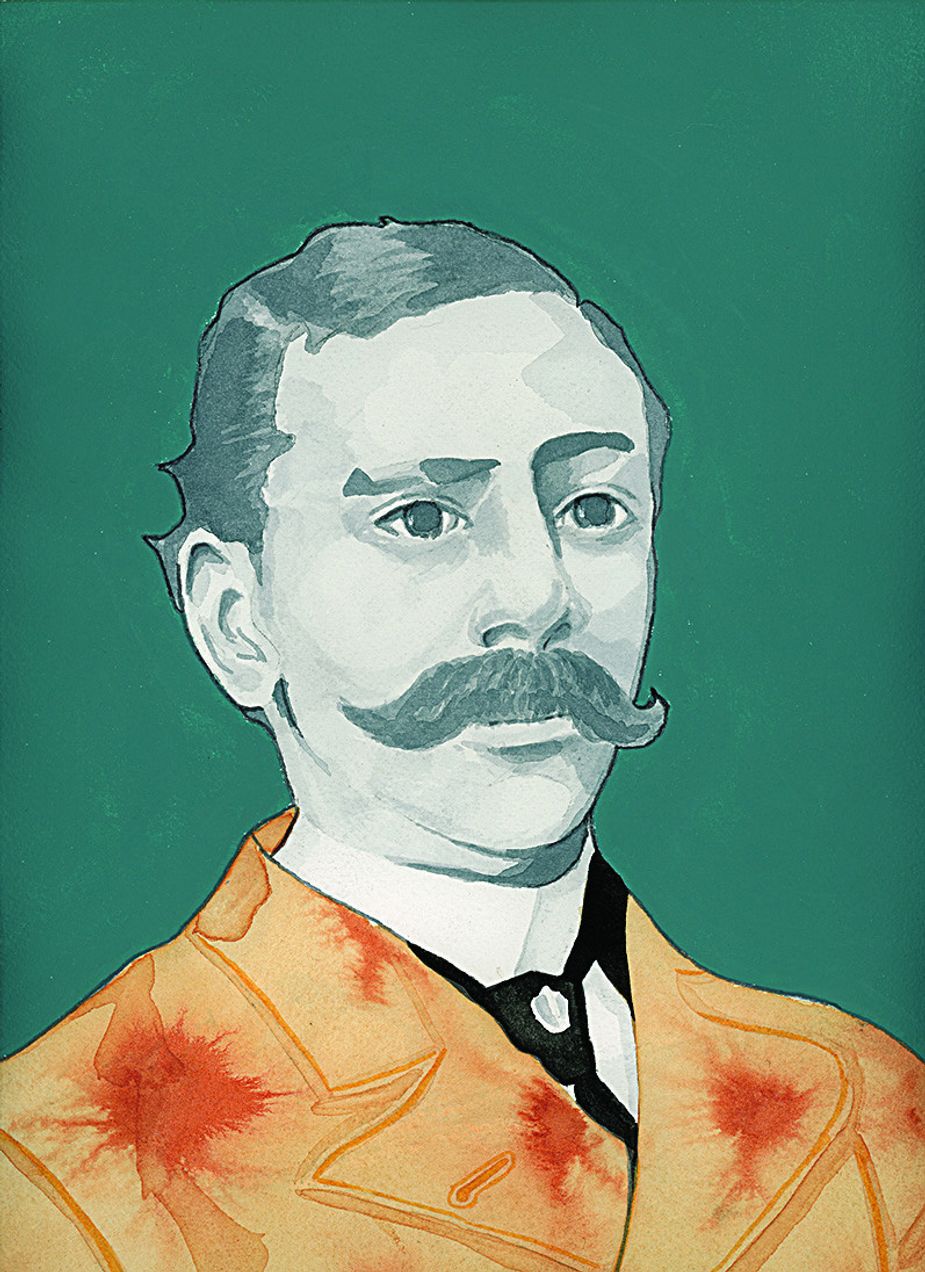

But it was a Kansas businessman, Edward (Edwin) P. McCabe, who envisioned Indian Territory as a new land of opportunity for black Americans free of the oppressive legislated racism of the post-Civil-War South. McCabe came to Oklahoma in 1890 after a visit to Washington, D.C., during which he visited President Benjamin Harrison to encourage his support for African American voting and civil rights. McCabe encouraged blacks to relocate to Indian Territory, an initiative that was assisted by the Oklahoma Immigration Association of Topeka, which called for the creation of Oklahoma as an all-black state with McCabe as its first governor.

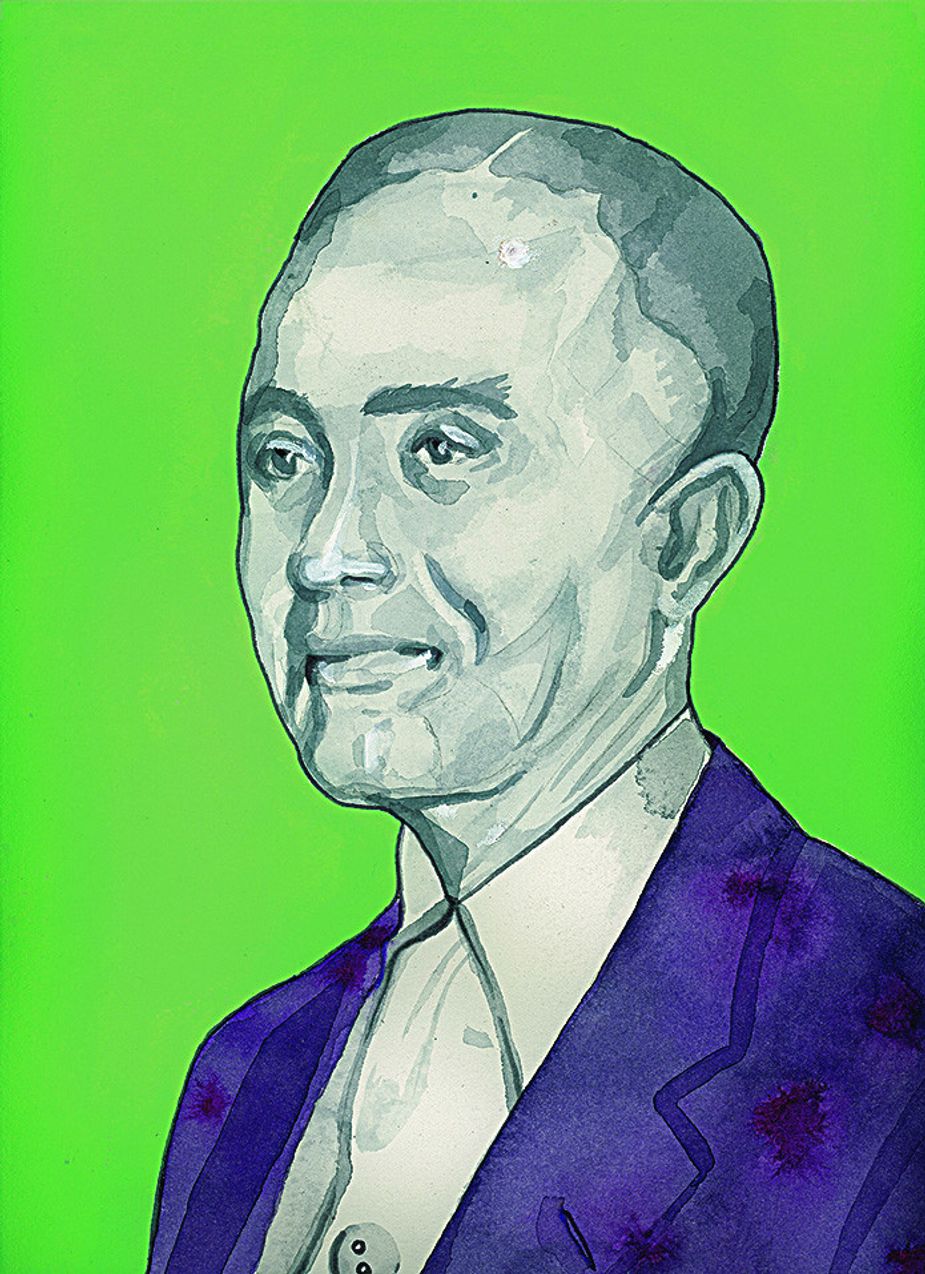

Businessman and Langston co-founder Edward (Edwin) P. McCabe.Portrait by Shannon Nicole

McCabe’s dream of an all-black state never became a reality, but he, along with white land developer Charles H. Robbins, established the town of Langston in 1890 and the Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal College—now known as Langston University—seven years later.

Langston was hardly unique. During this second migration of blacks to Oklahoma, as many as fifty all-black towns were established and served as testament to African Americans’ resolve to control their own destinies and live free of racism. Black Oklahomans bought farmland, established banks and other businesses, and ran for political office. Two black men, Green I. Currin and David J. Wallace, served in the Territorial Legislature prior to statehood during a time when school segregation by race still was optional—though in the late 1890s, the legislature passed statutes making it mandatory.

The Tullahassee Manual Labor School was a Creek Nation-funded boarding school opened for Freedmen in 1883. Tullahassee is one of the oldest historic all-black towns in Oklahoma. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Segregation and civil rights played a major role during the formation of a proper state on the land that was Indian Territory. At the 1906 Constitutional Convention, a “race distinction” passage formally separated school and transportation facilities. President Theodore Roosevelt even became involved, threatening to deny Oklahoma’s entry into the Union if the transportation provision, which he strongly opposed, remained in the state’s founding document. The clause was removed but swiftly reinstated by Oklahoma Senate Bill One, the first piece of legislation in the state’s history.

A.C. Hamlin, a Republican from Guthrie, was the first African American to serve in the new state legislature. Hamlin was elected in 1908 in the midst of a Republican renaissance in state politics, but his election prompted the legislature to draft a constitutional amendment requiring voters to pass a literacy test—one from which most white citizens were exempt—though this was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1915. In 1916, the legislature passed another clause denying blacks the right to vote. These actions reflected a larger trend across the South.

Oklahoma’s first African American legislator A.C. Hamlin. Portrait by Shannon Nicole

“. . . by 1910, the Negro had been effectively disenfranchised by constitutional provisions in North Carolina, Alabama, Virginia, Georgia, and Oklahoma,” wrote the late historian John Hope Franklin, a Rentiesville native, in his 1947 book From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes.

Despite a general atmosphere of legalized discrimination in housing, employment, transportation, education, and voting restrictions, black Oklahomans built a community unlike any America—or the world—had ever seen at the time. Tulsa’s Greenwood District, which came to be known as “Black Wall Street,” grew with Tulsa during the oil boom of the 1910s. The area contained thirty-five blocks of more than a hundred prosperous African American-owned businesses and residences. A dollar spent here would remain in the neighborhood for more than a year.

The area also was home to two newspapers, most notably The Tulsa Star. Andrew J. Smitherman, the Star's publisher, began his career by founding The Muskogee Star in 1912 before moving the operation to Tulsa in 1913. Through his newspaper, Smitherman shared his message of African American autonomy and encouraged armed resistance to combat lynching bees and other forms of racial violence. He authored searing editorials and poems that spoke to economic and racial disparities. In 1920, Smitherman was invited by Governor J.B.A. Robertson to participate in an interracial conference on the rampant lynching of black Oklahomans. When the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 broke out, many white Tulsans blamed Smitherman, and he was charged with inciting a riot by local courts. By this time, however, he had moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, and the case never was brought to trial because that state refused to comply with Oklahoma’s extradition efforts.

The Muskogee Star and The Tulsa Star founder A.J. Smitherman. Portrait by Shannon Nicole

The race massacre devastated the Greenwood neighborhood. More than three hundred black people were killed and 10,000 rendered homeless after white mobs set fire to businesses and more than a thousand homes in the area. Some even flew over the riot in their private planes dropping kerosene bombs to aid in the devastation. Many black Tulsans were imprisoned at several locations around the city, including a baseball stadium at McNulty Park. Afterward, black Tulsans walked back down Archer Street to bury their neighbors and sleep in makeshift tents amid the smoldering rubble of their own prosperity.

“Their scorched earth assault on the Greenwood District left little unscathed: homes and businesses reduced to charred rubble; scores dead, dying, and wounded; and hundreds homeless and destitute,” wrote Tulsa author, attorney, and black history scholar Hannibal B. Johnson. “The breadth and brutality of it all etched psychic scars palpable even today.”

During a protest, Oklahomans held a Jim Crow funeral at the State Capitol on August 28, 1963, which was the same day Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in the nation’s capital. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

About a hundred miles away, Oklahoma City had its own well-known black neighborhood. Freedmen had settled in the area following the Land Run of 1889, and by the turn of the century, they had claimed hundreds of jobs in the city’s warehouse district to the north of the Canadian River and east of the Santa Fe Railroad—an area now known as Bricktown.

In 1915, Oklahoma City officials fearful of integration passed one of the country’s initial segregationist housing ordinances, which bound blacks to an area along Northeast Second Street. This center of African American life became known as Deep Deuce and was the birthplace of renowned author Ralph Ellison and influential musicians Earl Grant and Jimmy Rushing as well as home to the groundbreaking jazz guitarist Charlie Christian.

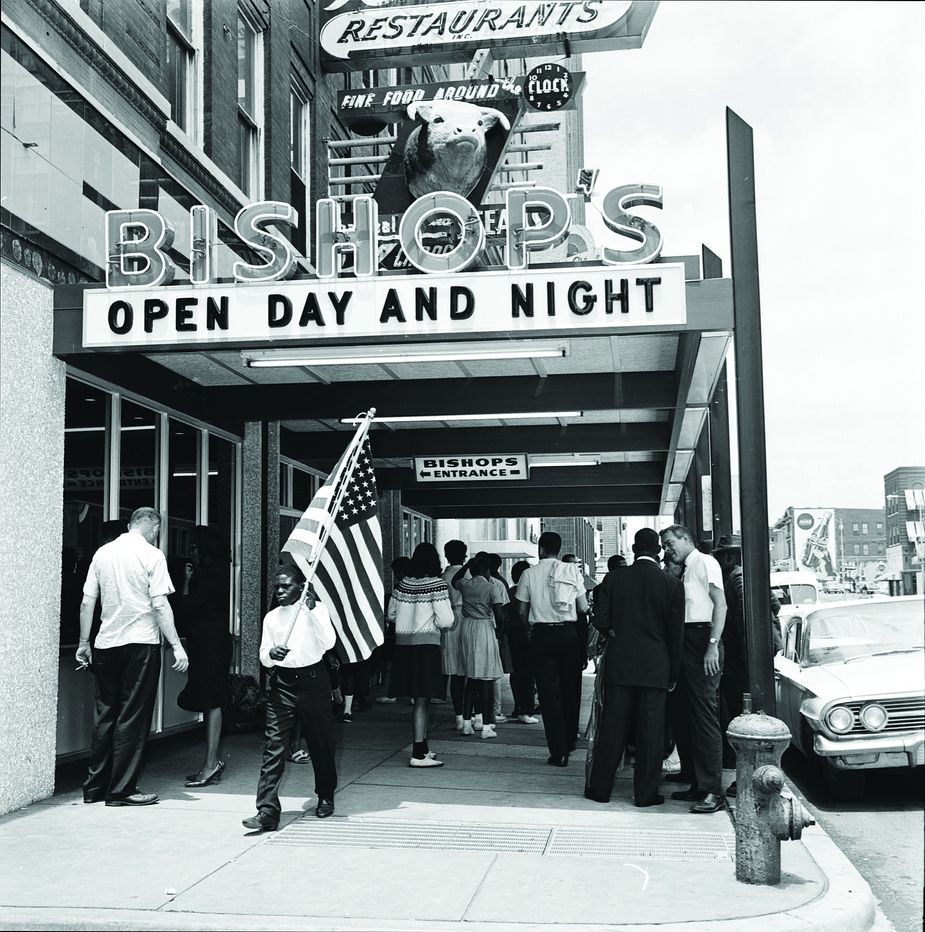

Protesters gathered at Bishop’s Restaurant in downtown Oklahoma City on June 1, 1963. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

But of all the city’s well-known black citizens, it was another newspaper owner who made Oklahoma City a center of civil rights activism during this time. Roscoe Dunjee established The Black Dispatch, the first newspaper for Oklahoma City’s African American community, in 1915, and he was its publisher until 1955. During this time, Dunjee, a moving writer and commanding speaker, became a leader in the civil rights struggle statewide and was a relentless supporter of black economic progress and unity.

Dunjee served as president of the National Negro Business League, and his Bricktown offices were home to the city’s branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He served on the NAACP’s national board of directors and created the first state conference of NAACP branches in the United States. Under Dunjee’s direction, the Oklahoma City NAACP was instrumental in many court cases challenging segregation in the Sooner State. Two of these cases in particular would prove to have national impact and provide momentum to the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, and both concerned the state’s flagship university.

In 1945, when Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher graduated from Langston University with honors, her goal was to attend law school. But Langston didn’t have its own law school, and state law at the time prevented blacks from attending white universities. So Roscoe Dunjee encouraged Fisher to apply to the University of Oklahoma College of Law in the spring of 1946.

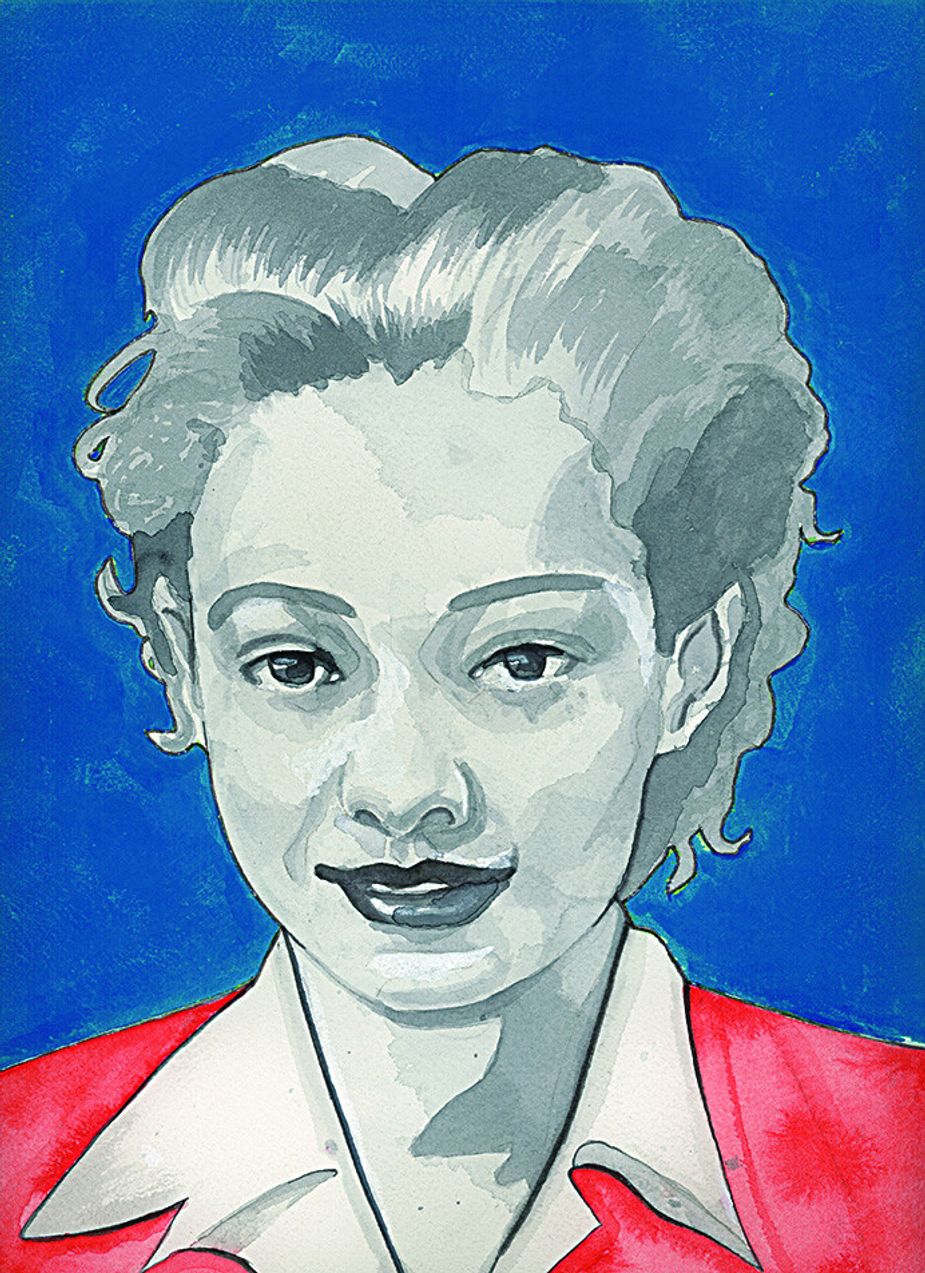

The University of Oklahoma’s first African American law student Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher. Portrait by Shannon Nicole

After being denied entry to the school on the basis of race—and with Dunjee and the NAACP behind her—Fisher filed a lawsuit in the Cleveland County District Court. After losing there and at the state Supreme Court, she filed an appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

Guided by Thurgood Marshall, who eventually became the country’s first black Supreme Court justice, the nation’s highest court ruled that Oklahoma must provide Fisher with the same opportunities for securing a legal education as it provided to other Oklahomans. The state legislature created a separate law school for Fisher, housed in rooms at the State Capitol, rather than allow her to set foot on OU’s campus. With Marshall’s help, Fisher appealed this situation as not equal per the Supreme Court’s edict. She finally was admitted to OU’s College of Law in 1949, but she could only sit in the back of the room and was forced to eat, study, and watch football games in areas separate from the white students.

Despite these additional barriers, Fisher received her law degree in 1952, served as a professor and administrator at Langston until 1987, and was named to OU’s Board of Regents in 1992. She died in 1995.

A civil rights march on June 6, 1964, at the State Capitol drew around 150 marchers both black and white. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Around the same time Fisher’s case was gaining steam, another school segregation case was making its way through state courts. Sixty-one-year-old George W. McLaurin was one of six black Oklahomans who applied for undergraduate admission to OU in 1948. All were denied admission. Once again, Thurgood Marshall was eager to help, and soon, the case stood before the U.S. Supreme Court, which found that segregation inhibited McLaurin’s ability to study. This effectively ended segregation not only at OU but at all other state-supported universities throughout the nation.

This case, McLaurin v. the Oklahoma State Regents, was pivotal to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren’s later attempts to make clear that segregation was, by its very nature, unequal. McLaurin and Fisher’s cases were precursors to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case that led to the end of school segregation nationwide. Without these pioneering Oklahoma fights for equality, the Civil Rights Movement that grew across the country in the years that followed may have unfolded very differently.

Without a doubt, one of the most famous points of contact between the statewide struggle for black civil rights and the national movement was during the fight for the end of Jim Crow laws. In Oklahoma, that fight was led by Clara Luper.

Teacher and community organizer Clara Luper. Portrait by Shannon Nicole

In 1958, Luper, a public school teacher at John Marshall High School, led thirteen young people from the NAACP Youth Council to Katz Drug Store in downtown Oklahoma City to stage a “sit and wait” protest. At Katz, she and the other protesters ordered lunch and were asked to leave. The group remained at the counter and respectfully asked to be served. The group endured threats, insults, and spit from angry white customers for two consecutive days. Under public pressure, Katz staff served the group burgers and sodas on the third day. The Katz chain ended its segregation policy shortly after the Oklahoma City sit-in in all thirty-eight of its stores in four states. Luper continued to lead sit-ins and marches until 1964.

The Oklahoma City sit-ins occurred a year and a half before the country’s most famous sit-in, at the Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, North Carolina. In Oklahoma, Luper was jailed twenty-six times for her activism, but her example—plus the success of sit-ins and marches nationally as well as the devastating assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and John F. and Robert Kennedy—galvanized young people anxious for progress. During the 1960s and ’70s, student walkouts occurred statewide as African American youth demanded greater representation in terms of teachers, course content, and access. More African Americans ran for and were elected to political office, including Hannah Diggs Atkins, the first black woman elected to the state House of Representatives. She went on to serve as Oklahoma’s secretary of state from 1987 to 1991.

Ayanna Najuma, center, participated in the Katz Drug Store sit-in in Oklahoma City when she was only seven years old, along with a number of other children from the NAACP Youth Council. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Today, most of Oklahoma’s all-black towns have disappeared or been unincorporated—though a handful, including Boley and Langston, still remain. But African American civil rights leaders in the state understand the mighty shoulders on which they stand and from which they still advocate.

“As we continue the struggle toward equality and equal opportunity, the best strategies of today are rooted in the historical acts, commitments, and successes of those who came before us,” says Michael Eric Owens, founder and executive director of the Oklahoma City-based Ralph Ellison Foundation.

The significance of the Sooner State in the African American struggle for civil rights continues to leave indelible imprints on the nation’s parchment. Oklahoma is one of the youngest states in the Union, and the concerns, as well as triumphs, of its past remain both burdens and opportunities.

As Luper once said, “My biggest job now is making white people understand that black history is white history. We cannot separate the two.”

Long Road to Liberty: Oklahoma's African American History & Culture

The Long Journey

Learn more about African Americans’ history in Oklahoma from the Trail of Tears through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and into the present day at these events and sites all over the state.

The John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, Greenwood Cultural Center

322 North Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa, (918) 295-5009 or jhfcenter.org

John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park

290 North Elgin Avenue in Tulsa

Tulsa Historical Society & Museum

2445 South Peoria Avenue in Tulsa, (918) 712-9484 or tulsahistory.org

Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame

5 South Boston Avenue in Tulsa, (918) 928-5299 or okjazz.org

Oklahoma Black Museum & Performing Arts Center

4701 North Lincoln Boulevard in Oklahoma City, (405) 213-8077 or naajlm.com/obmapac

Charlie Christian International Music Festival

June 1-3 at the Montellano Event Center, 11200 North Eastern Avenue in Oklahoma City

Ralph Ellison Library

2000 Northeast Twenty-third Street in Oklahoma City, (405) 424-1437 or metrolibrary.org/ralph-ellison-library

Oklahoma History Center

800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive in Oklahoma City, (405) 522-0765 or okhistory.org

Honey Springs Battlefield and Visitor Center

101601 South 4232 Road in Checotah, (918) 473-5572 or okhistory.org/sites/honeysprings

Fort Sill National Historic Landmark & Museum

435 Quanah Road in Fort Sill, (580) 442-5123 or sill-www.army.mil/museum

Answering the Call Buffalo Soldier Monument

Buffalo Soldiers Heritage Plaza, 200 West Gore Boulevard in Lawton

Fort Gibson Historic Site

907 North Garrison Avenue in Fort Gibson, (918) 478-4088 or okhistory.org/sites/fortgibson

Bass Reeves Western History Conference

July 26-27 at the Three Rivers Museum, 220 Elgin Street in Muskogee, (918) 686-6624 or bassreevesconference.com

Boley Historical Museum

Open by appointment. 10 West Grant Street in Boley, (918) 667-9790

Rentiesville Museum and Oklahoma Blues Hall of Fame

103020 D.C. Minner Street in Rentiesville, (918) 855-0978 or dcminnerblues.com

Rentiesville Dusk ‘til Dawn Blues Festival

August 30-September 1 in Rentiesville.

(918) 855-0978 or dcminnerblues.com

For more on Oklahoma’s black history, order the Long Road to Liberty or visit TravelOK.com/long-road-to-liberty