True Crime

Published June 2025

By Clayton Trutor | 18 min read

Pawnee’s Chester Gould created one of the most memorable figures in the history of American popular culture: Dick Tracy, the newspaper comic he began in 1931, runs to this day and remains one of the most widely read and influential strips in comic history. The angular detective in the yellow trench coat and felt hat recalled numerous other hard-boiled detectives of the era: The likes of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Jack Webb’s Joe Friday, and even Batman bear more than a passing resemblance to Tracy, who was modeled after real-life FBI agent Eliot Ness.

Gould wrote the strip for forty-six years, from 1931 to 1977—and his signature remained on the strips until 1981. In 1959 and again in 1977, his peers at the National Cartoonists Society honored him with the Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist. In 1995, Tracy appeared on a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service. The entirety of the Dick Tracy strip remains in print through The Library of American Comics. The series has spawned radio and television productions, feature-length films, and extensive merchandising. Tracy’s likeness has appeared on toy guns, detective kits, and two-way radios, among other things. And it all began in Pawnee.

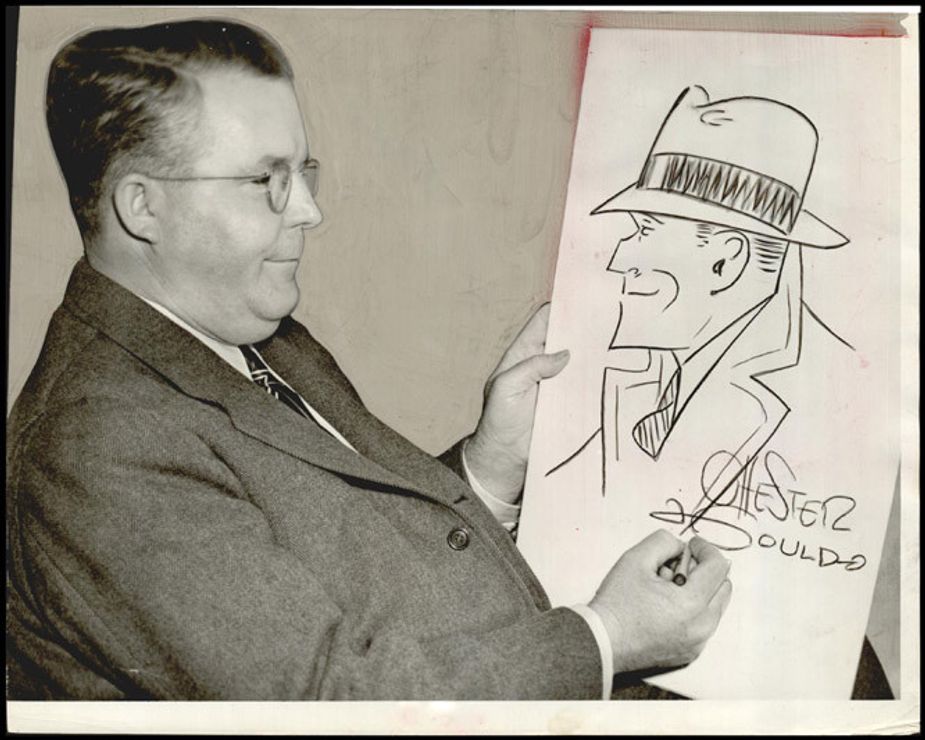

Chester Gould, pictured in 1941 with a sketch of the character who made him famous, wrote and drew the *Dick Tracy* comic strip for 46 years. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Chester Gould was born on November 20, 1900, in a log cabin near Pawnee in the Oklahoma Territory. His parents, Alice (née Miller) and Gilbert Gould, both came from families that were among the original white settlers in the Territory. They eventually settled in a home on the more agricultural west side of town.

Gilbert was a newspaper man, serving for years as editor of the Pawnee Courier-Dispatch. His father’s profession gave young Chester an early vantage point into the world where he spent his adult life. Gilbert often brought home Chicago newspapers from Pawnee’s newsstand, and he encouraged his son to draw, even posting his sketches in the front window of the newspaper office. During adolescence, Chester took correspondence courses to learn more about caricature and cartooning.

Chester went by the nicknames Chet and Ches during his early years. As a teenager, he started entering cartooning contests in magazines and frequently won first place, including one for American Boy magazine. In high school, he painted advertisements on the sides of local buildings and barns.

Chet’s work got sufficient notice to impress a yearbook editor at Oklahoma A&M. He did drawings and calligraphy for the publication in 1918 and 1919 before enrolling at the school for the 1919-1920 year. While in Stillwater, he took primarily business courses and for two years continued to serve as the yearbook’s cartoonist. On the side, he sold freelance cartoons to The Daily Oklahoman and the Tulsa Democrat. After his sophomore year, he moved to Chicago to get a daily comic of his own picked up by the Chicago Tribune and its syndicate. He started taking classes at Northwestern University’s night school, completing a bachelor’s degree in business in 1923.

Gould also freelanced as an editorial and sports cartoonist for the Tribune and the Chicago Daily Journal. He even wrote a few short-lived comic strips. For years, he submitted ideas for strips to Tribune editor Joseph M. Patterson—to no avail. Gould spent the back half of the 1920s working for William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago Evening American.

He married Edna M. Gauger in 1926. The couple had their only child, a daughter named Jean, a year later. In later years, Jean helped her father as an illustrator, one of many such assistants who worked with Gould over the years. Despite leaving Pawnee, Gould remained in close contact with friends and family in the region. Old teachers and classmates received letters and sketches from him regularly.

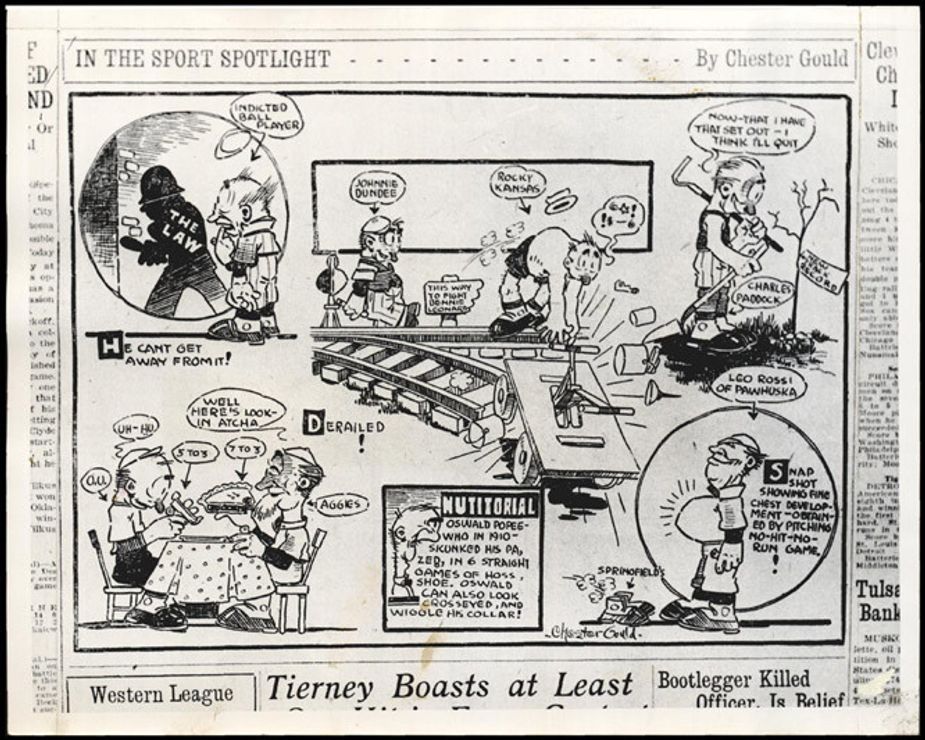

Gould created comics for several publications in his youth. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

In the summer of 1931, Gould tried a new tactic: He incorporated headlines about Chicago’s ongoing Prohibition-era gang wars into a new pitch aimed at Patterson. He adopted front page headlines into a melodrama designed for the funny pages. He steeped his mockups in the story lines of Eliot Ness and Al Capone. Gould called his new character Plainclothes Tracy and clad him in a yellow trench coat and a felt hat. This would be the first detective comic, its story lines playing out over months and years. Tracy would be part Eliot Ness-style crime fighter and part Sherlock Holmes-style scientific investigator, and his first target would be Big Boy, a less-than-subtle take on Al Capone. Despite its spot on the funny pages, the stories would be grim and unflinchingly serious. Patterson liked the concept but not the name. He suggested Dick as a replacement first name, since everyone used the term as shorthand for a detective.

The first Dick Tracy cartoon ran on October 4, 1931, in the Detroit Mirror, a paper in the Tribune’s syndicate. Within weeks, it was appearing across the country, both as a daily and in Sunday editions. For the next forty-six years, Gould filed dailies and Sunday page versions of Dick Tracy for an audience that grew to nearly a thousand papers in the late 1950s. Gould never missed a submission deadline.

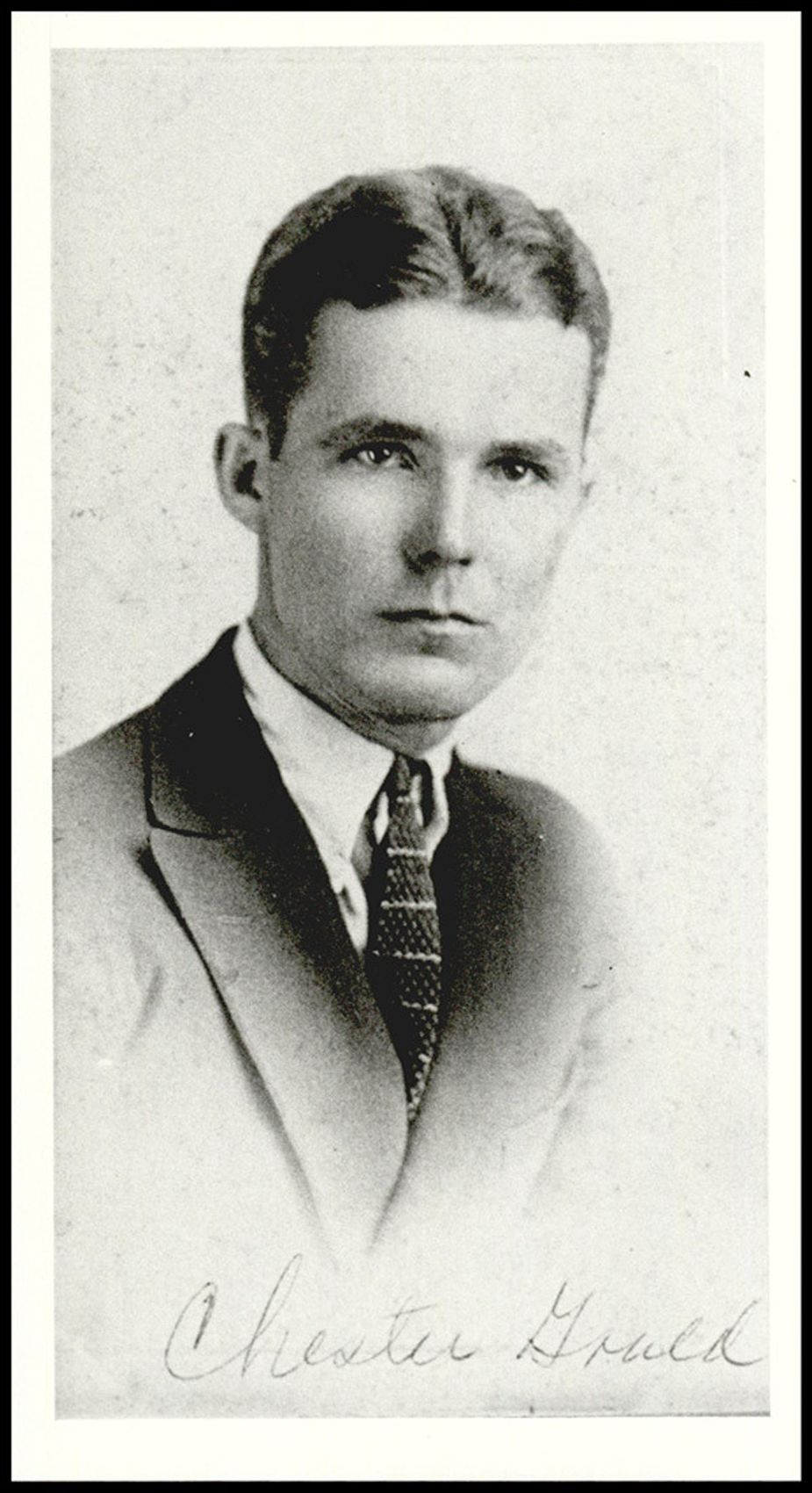

Illustrations by Gould appeared in Oklahoma A&M's 1918 yearbook. Image courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Dick Tracy’s cluster of defining features made it a huge hit with young readers. It had the tough talk of contemporary crime fiction and film. It offered readers a suspenseful, ongoing saga steeped in the grotesqueries of gangland violence. There were no shades of gray in Dick Tracy. The bad guys were as sadistic and strikingly grotesque as any villains imaginable. His cast of rogues included the distorted visages of Pruneface and the Mole; the odiferous B.O. Plenty; Flyface, a corrupt lawyer perpetually surrounded by pestilence; and Flattop, whose head was the shape of an aircraft carrier—he was a takeoff on Oklahoma’s own media-friendly villain, Pretty Boy Floyd.

Violence was front and center in Dick Tracy from the beginning. In the first daily strip, the father of Tracy’s girlfriend, Tess Trueheart, is murdered by thieves in his grocery store. This was the first-known murder on the funny pages. The incident provoked Tracy to take the law into his own hands, and soon thereafter, the police department hired him as a detective. From day one on the force, Tracy adopted a take-no-prisoners approach. He wasn’t afraid to gun down, impale, or sic a rabid dog on his adversaries. In one instance, he bombed the villains’ headquarters with napalm. His body count was well into the hundreds.

Tracy’s family, too, was subject to violence. After an eighteen-year engagement, the detective married Tess Trueheart. They had a daughter named Bonnie Braids and an adopted son named Junior. Frequently, the family suffered through the dastardly deeds of Tracy’s many villains.

Critics scolded Gould for the graphic carnage featured in his strip as well as the awful-looking bad guys he created. Later in the comic’s run, critics jabbed at Gould for Tracy’s evident indifference to the rights of the accused.

“. . . Dick Tracy, not only fails to justify his commercial exploitation of violence but also reveals himself in the type of fascist-oriented thinking his ‘comic’ strip portrays,” wrote reader G. Lloyd Wilson in the June 30, 1968, Los Angeles Times. Decades earlier, Gail Borden of Gould’s own Chicago Tribune critiqued a 1940 strip in which the protagonist had violently tuned up a suspect in handcuffs.

Regardless of the criticisms, Dick Tracy found an audience far beyond the dailies. It became a popular radio drama in the 1930s before becoming a movie serial. A series of feature-length Dick Tracy films appeared in the 1930s and ’40s starring Ralph Byrd. After years in development, Warren Beatty brought a flashy, big budget, heavily merchandized Dick Tracy film to cinemas in 1990.

Dick Tracy Headquarters is located at the Pawnee County Historical Society. Photo by Saxon Smith

Fans of Dick Tracy and pop culture in general will delight in the large collection of art and memorabilia at the historical society. Photo by Saxon Smith

In 1935, Gould purchased a farmhouse in Woodstock, Illinois, about fifty miles northwest of Chicago. He, Edna, and Jean kept animals and maintained an active farm, and Gould commuted regularly into the city for several years before bringing his work home permanently. He lived and worked in Woodstock for the rest of his life.

But he was not one to rest on his laurels. He put great effort into keeping abreast of the latest developments in the techniques of law enforcement. While at Northwestern, he had taken courses in criminology and ballistics. He visited Chicago’s municipal crime lab regularly to study cutting-edge investigative procedures. He also made visits to FBI headquarters and Scotland Yard to learn about forensics. In the 1950s, he hired a retired Chicago policeman named Al Valanis to review his strips for accuracy. Gould anticipated such inventions as a two-way wristwatch, caller ID, video surveillance, and the pager in his cartoons.

The concept of Crime Stoppers also originated in Dick Tracy during the 1940s. Initially, a story line had Tracy’s son Junior organizing a group of crime-fighting youths. Then Gould added a panel titled “Crimestopper’s Textbook” to his Sunday comics with tips on crime prevention. The actual police force in Woodstock took on the idea, turning it into a youth mentoring program. Eventually, Crime Stoppers evolved into its current form as a crime tip line.

In the 1960s, Gould also experimented with a series of space travel- and science fiction-related story lines, including the marriage of his adopted son Junior to a woman called Moon Maid. In the 1970s, the character of Dick Tracy adopted a more hirsute and contemporary look while adopting a more Dirty Harry-like persona—an old-school crime fighter who didn’t cotton to newfangled ideas like Miranda warnings and citizen review of police activity.

Gould’s final comic appeared on the Sunday page on Christmas Day 1977. Since then, a series of writers and illustrators have kept it going to the present day.

Originating from the comic, Crime Stoppers became a youth program in Woodstock, Illinois, where Gould lived. Photo by Saxon Smith

Dick Tacy's Copmobile and other memorobilia can be found inside Dick Tracy Headquarters in Pawnee. Photo by Saxon Smith

Chester Gould died of congestive heart failure on May 11, 1985, on his farm in Woodstock after suffering a debilitating heart attack.

Not long after Gould’s death, Warren Beatty’s long-in-the-works Dick Tracy movie began production. It was released in 1990, spurring a renewed interest in the strip.

“The man himself—Chester Gould,” Beatty gushed—in character as Tracy—to film critic Leonard Maltin during a 2010 interview for the film’s twentieth anniversary. “I trusted him to stay true to my character, and he did it. I always thought that the most important thing was to get the message out to young people that crime does not pay.”

Soon after the movie’s release, two Dick Tracy museums opened: one each in his hometowns of Pawnee and Woodstock. The Woodstock Museum closed in 2008, and much of its collection ended up in Pawnee at the Pawnee County Historical Society’s museum, which continues to host Dick Tracy Headquarters—a treasure trove of Dick Tracy memorabilia that is a must-see for any fan.

“Dick Tracy is the biggest draw,” says Dodie O’Bryan, president of the museum. “We had a man fly in from Mexico just to see Dick Tracy Headquarters.”

The society hosts an annual “Dick Tracy Day” every October to commemorate the detective’s birthday. As part of the festivities, police cruisers from across Oklahoma parade through Pawnee with lights flashing and sirens blaring.

This wall of the Prairie Rose building in Pawnee recently was demolished, but there are plans to resurrect Ed Melberg’s mural, seen here. Photo by Saxon Smith

Few of Gould’s known family members remain in the Pawnee area, but O’Bryan says there are a few cousins who visit occasionally. A mural of Tracy by Tulsa-based artist Ed Melberg and his sign company, Sign Excellence, adorned the side of the Prairie Rose building in downtown Pawnee. The wall recently was demolished, but there are plans to resurrect the mural on the structure that replaces it. The legacy of Chester Gould and his world-famous character are in great hands in Pawnee. Dick Tracy’s continuing popularity will keep people visiting for years to come.

There is a timeless quality to Gould’s protagonist. Amid the ever-present shades of gray, Dick Tracy offers readers a sense of certainty that the good guys are the good guys and the bad guys will be punished.

Dick Tracy Day in Pawnee is October 4 this year. (2025)