Smooth Criminal

Published July 2024

By Jim Logan | 18 min read

On a November afternoon in 1932, writer Vivian Brown returned to her home in Muskogee to find a stranger parked out front. When the man told her who’d sent him, she got into the car. In silence, the two drove over country roads for thirty miles, stopping in a secluded pecan grove. Nearby was a tan V-8 Ford; two men got out. One she recognized as a man she’d spoken with earlier. The young man with him was of medium build, neatly groomed, with dark brown hair and blue-gray eyes and wearing a tailored suit, white shirt, and tie. She recognized him from photographs as the wanted outlaw with a $6,000 price on his head—Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd. Weeks earlier, she’d requested an interview for a book she was working on about him.

Floyd politely introduced himself, and, with Brown transcribing his words in shorthand, the two talked for hours. Raised by God-fearing Georgia Hill Country farmers, he’d moved at age seven to eastern Oklahoma, where his family had settled as tenant farmers near Akins in Sequoyah County. In his teens, he’d traveled with harvest crews, from whom he’d learned some bad habits—bootlegging and the like. At twenty, he’d married Ruby Hardgraves, a pretty, part-Cherokee daughter of tenant farmers. Soon after, she’d given birth to their son, Charles Dempsey Floyd.

Struggling to support his family, he and a friend had hopped a train to St. Louis, where they’d become involved in a grocery payroll robbery. Eventually arrested, he spent four years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. In his words, he was “. . . just a Green Country kid that got caught in a job that I didn’t know much about.”

He talked of prison life and how it taught him most of what he knew about crime. Of his purported killings, he said, “I’ve never shot at a fellow in my life, unless I was forced into it by some trap being thrown to catch me . . . and then it was that or else.”

Regarding his many bank robberies, he said, “It was all bonded money, and no one ever lost anything except the big boys.”

He spoke of the many impersonators and falsehoods attributed to him and of his love for his young son and family.

Sometime after dark, the two said goodbye, and Brown was driven back to her home. Through it all, she’d been treated with the utmost courtesy. It would be the only interview Pretty Boy Floyd ever gave.

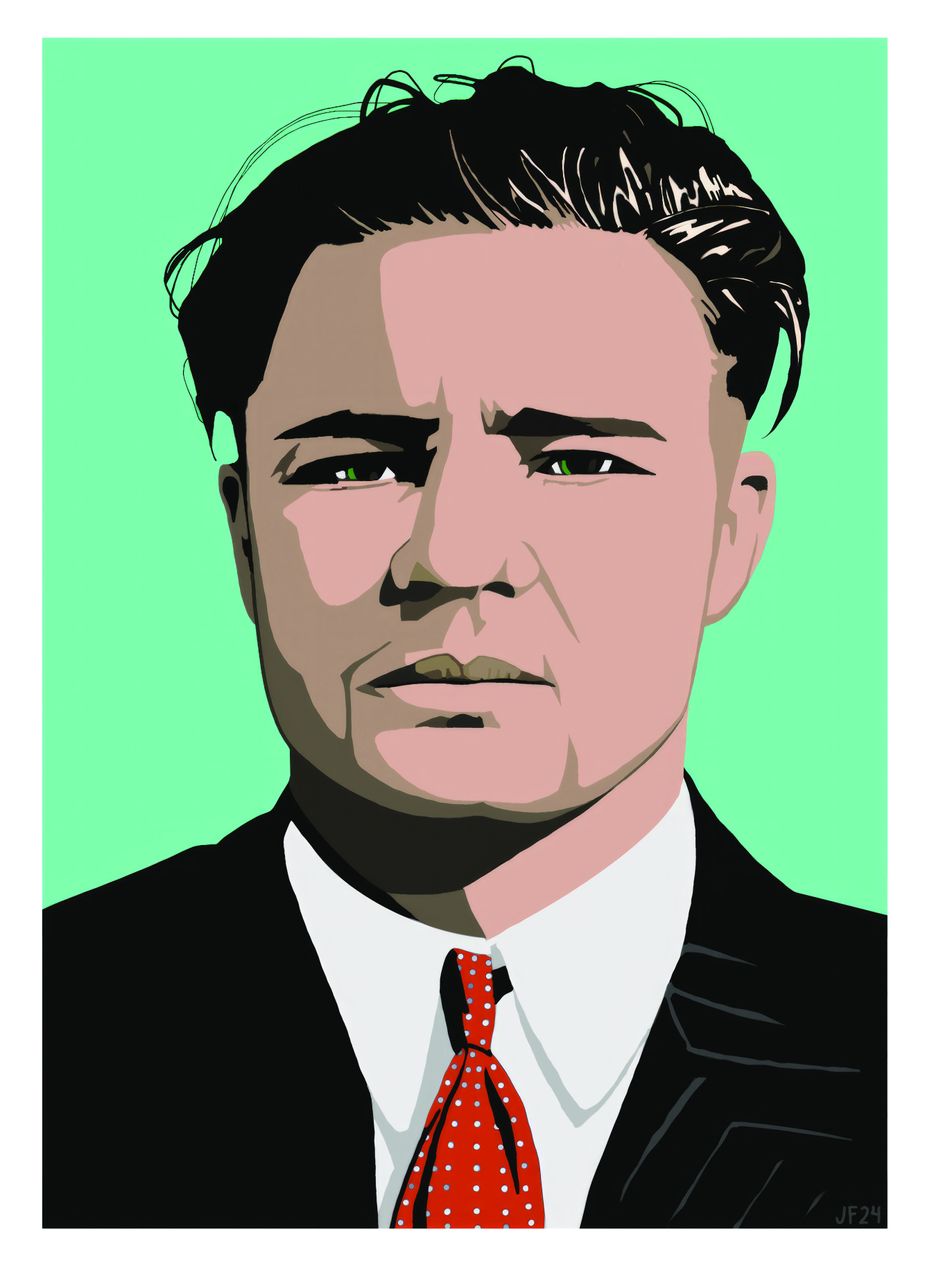

Pretty Boy Floyd portrait by Jack Fowler

At the start of the Great Depression, American farmers were earning $273 annually compared to the national average of $750. For the half of Oklahoma farmers who were tenants, hard times already had begun. With Floyd’s blessing, Ruby filed for divorce during his fourth year in prison, citing neglect due to his incarceration. Despite her remarriage and Floyd’s known involvement with other women after his prison release in 1929, she and her young son soon left her new husband to reunite with Floyd. The couple lived together intermittently with their son in Arkansas and Tulsa—under assumed names and as circumstances allowed—until his death.

Floyd made an initial attempt to go straight after his release from prison, hiring on as a worker in the Seminole oil fields. When it was discovered, however, that he’d served time behind bars, he lost that job. He headed for Kansas City, which harbored many ex-cons—some of whom he knew from prison.

It was in Kansas City, during a boarding house card game, that Floyd is believed to have acquired his nickname. He’d recently returned from the barber and was sharply dressed, sporting a new tie, and flush with cash from a recent bootleg liquor run. Beulah Baird, the young and beguiling daughter of the boarding house owner, placed a glass of booze in front of him. Taking a seat beside him, she supposedly remarked, “Hello, pretty boy. Where did you come from?” He won the card game and—despite her marital status—the two began a serious relationship. He never personally liked the nickname, preferring “Charley” or “Choc.”

This .38 Colt automatic was taken from Floyd by a detective in Kansas City. The gun now is on display at the J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum in Claremore. During a cleaning, the museum staff discovered a getaway map carved into the back side of one of the pistol’s grip panels. Photo courtesy J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum

A steady portion of Floyd’s income came from running bootleg Kansas City liquor into Oklahoma. But it was by no means the only one: He was arrested in Ohio following a bank robbery but escaped while being transported to the Ohio State Penitentiary. From 1930 to 1934, more than thirty successful bank robberies across mostly Oklahoma and Ohio followed.

He worked in broad daylight and with no mask—usually with just a single partner and a getaway driver. He primarily targeted small-town banks—including those in Maud, Morris, Earlsboro, Konawa, Castle, Stonewall, and Sallisaw, to name a few—with the usual take between two and four thousand dollars.

Dressed in a suit and tie and armed with a machine gun and .45 revolver, he entered a bank with a partner, announced his intentions, and proceeded in a courteous, businesslike manner. Money in hand, the two would leave with two or three employee-hostages, who were instructed to ride on the getaway car’s running boards to discourage any shots being fired at them. The hostages were told, “Hold on tight, and don’tcha worry,” and were released when the car was safely out of town.

Floyd made every effort to avoid violence. While accused of several killings, he’s known to have committed only two. The first involved policeman Ralph Castner during a 1931 shootout in Bowling Green, Ohio, in which his partner, Willis “Billy the Killer” Miller, was killed, and Floyd escaped. The second occurred near Bixby a year later, when his car was ambushed by noted lawman Erv Kelley and eight others. In the early morning shootout, Kelley was killed, and Floyd was hit four times but escaped. And while his involvement never was proven, he was a chief suspect in the unsolved Kansas City killing of Baird’s jealous husband.

This mask of Floyd’s face was made after his death on October 22, 1934. Photo courtesy the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Ironically, Floyd came to be viewed by many across the Midwest as something of a Robin Hood figure. At a time when banks were foreclosing on thousands of homes and farms, he was known to destroy bank mortgages during robberies. Hostages reported being treated kindly. Once, finding it necessary to appropriate a family’s car, he returned the $140 in traveler’s checks they’d handed over to him. He typically left money at a farmhouse after a meal or overnight stay. When on the road, he often drove while listening to his partner George Birdwell reading the Bible.

Friends and family described him as generous to a fault. When relatives told him about a nearby poor family, he purchased a supply of groceries for them—then added money for shoes. When he was eating in a restaurant and was approached by a hungry man, he told the owner to give the man all he wanted, then handed the man an extra twenty dollars. He paid doctor bills for friends and relatives when needed, left candy bars beneath their kids’ pillows when spending the night, and, whenever possible, attended family funerals, baptisms, and weddings. He was known to tip generously and buy ice cream for kids in drugstores. Following a holdup of the Sallisaw State Bank, Floyd told his partner to leave several spilled rolls of coins on the sidewalk for youngsters nearby. His son, years later, recalled it being like Christmas whenever his dad came home.

Hundreds of spectators gathered outside the Kansas City Union Station following what was known as the Kansas City Massacre—an alleged attempt by Floyd and two other men to free their friend Frank Nash while he was in transit back to the Kansas Penitentiary, from which he had recently escaped. The criminal team ambushed the FBI agents, and several men were shot to death—including Nash. Photo courtesy the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Floyd attracted national headlines in 1932 following a series of shootouts and sensational escapes from police raids on his Tulsa living quarters—despite their use of tear gas, an armored car, and nearly twenty officers. Bankers and Governor Alfalfa Bill Murray began calling for Floyd’s head in what became a national hysteria.

Then, in June 1933, a federal prisoner, one FBI agent, and three policemen were killed in a shootout at Kansas City’s Union Station—the incident became known as the Kansas City Massacre. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover placed a large share of the blame on Floyd, who claimed he’d had no involvement and even sent a postcard to authorities stating as much. Hoover’s interest in Floyd had heightened with the killing of the FBI agent, and the bureau became involved in the nationwide hunt for him. Floyd’s family, associates, and even Kansas City’s chief of detectives always maintained his innocence in the matter.

Along with Beulah Baird, her sister Rose, and his partner Adam C. Richetti, Floyd hid out in Buffalo, New York, for more than a year. In July 1934, Hoover declared him Public Enemy Number One—a pronouncement that ultimately proved fatal. In October, his brother Carl Bradley received a note from him saying, “We’re coming home.”

On their return, a weather-related accident near East Liverpool, Ohio, necessitated auto repairs, and the two women took the car to a local shop while the men camped on nearby farmland. The men were spotted by the landowners, who alerted local police. Following an exchange of gunfire, Floyd escaped, and his partner surrendered. At a nearby home, Floyd commandeered a vehicle, which ran out of gas. When he stole a second vehicle, he was pulled over by a deputy sheriff and a Lisbon, Ohio, police officer. A shootout ensued, and Floyd escaped into the nearby woods. His machine gun had jammed, and he was armed now only with a pair of pistols. After it became apparent that Floyd was likely the other fugitive, Hoover’s top man, Melvin Purvis—who’d recently taken down John Dillinger—flew in with a dozen handpicked agents.

For two days, more than two hundred men scoured the countryside in search of Charles Floyd. On the afternoon of October 22, he stopped at the farm of widow Ellen Conkle, saying he was lost, and asked for food. She prepared him a meal of spareribs, potatoes, bread, coffee, rice pudding, and pumpkin pie. When she refused payment, he insisted she take a dollar bill. When he told her he needed to get to a bus station, Conkle arranged for her brother and his wife to give him a ride into town.

As he was leaving with them, two cars with eight armed agents and police—including Purvis—entered the farmhouse lane. Floyd told the couple to stop the car, choosing not to take hostages. He got out and ran through an adjacent cornfield. Ordered to halt, he continued running, and on Purvis’ command, the group opened fire. Hit once, Floyd went down but got up and continued for a line of trees. A second volley brought him down again. As he lay bleeding badly, Purvis asked him if he was Pretty Boy Floyd.

“I’m Charles Arthur Floyd,” he replied. Minutes later, his life ended as it had begun—on a hardscrabble farm. As Michael Wallis wrote in his 1992 biography, Pretty Boy: The Life and Times of Charles Arthur Floyd, “He would be thirty years old forever.”

Floyd’s family and friends raised money for his body to be transported home by train. At his funeral, his former wife Ruby and Beulah Baird—both of whom he’d loved and who’d remained loyal to him until the end—were in attendance. In Ohio, Ellen Conkle later would receive two letters from Ruby, thanking her for the kindness shown to Charles. J. Edgar Hoover revealed that Floyd had written to Governor Murray, offering to surrender himself in return for immunity from the death penalty.

Melvin Horace Purvis was an FBI special agent in charge of the Chicago field office. He was part of the team that brought Floyd down in Ohio. Opposite page: An undated mug shot of Floyd—one of many taken over the years. Photo courtesy the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Folk hero or public enemy? Both beloved and feared, Charles Arthur Floyd was the most glorified Oklahoma outlaw in history. His name is woven into the cultural fabric. Ma Joad eulogized him in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. He was immortalized in song by Woody Guthrie. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana coauthored a biographical novel, Pretty Boy Floyd, in 1994.

At a time when banks were looked on by many with disfavor, Pretty Boy Floyd became the embodiment of a certain moral fairness to a great many of the downtrodden and dispossessed. A telling measure of his legacy lies in the fact that more than twenty thousand mourners engulfed the tiny Akins cemetery on October 28, 1934—the largest funeral gathering in Oklahoma history.

Akins Cemetery

› Pretty Boy Floyd is buried in a small cemetery about ten miles north of Sallisaw.

› From Sallisaw, drive north on U.S. Highway 59 about three and a half miles, then turn east on State Highway 101. After about five and a quarter miles, the cemetery will be on the right.

.jpg)