Oklahoma's Dark Poet of Crime

Published December 2023

By Jim Logan | 16 min read

Of the many intriguing facts surrounding the life of Oklahoma-born crime writer Jim Thompson, one of the most surprising remains his relatively unknown status among so many in his home state. His nearly thirty published pulp novels have been adapted into ten motion pictures. His characters have been portrayed on the silver screen by the likes of Steve McQueen, Ali MacGraw, Kim Basinger, Alec Baldwin, Annette Bening, John Cusack, Kate Hudson, Jessica Alba, and William H. Macy. He wrote screenplays for film directors Stanley Kubrick and Robert Redford.

“My favorite crime novelist—often imitated but never duplicated—is Jim Thompson,” wrote Stephen King in a 2011 foreword to Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me, which King called “an American classic that deserves space on the same shelf with Moby-Dick, Huckleberry Finn, The Sun Also Rises, and As I Lay Dying.” In France, he’s been hailed as one of the great American writers of the twentieth century.

His works drew largely from personal experience and people he’d known, and, despite his many big-city story settings, his novels clung essentially to the three original vistas of his life: Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas. His stories have an air of authenticity; at one time or another, he’d worked at nearly all the same jobs as his more memorable characters. He was known to frequent bars and coffeehouses favored by off-duty policemen, and, on getting to know many of them, often was allowed to ride along on their night beats.

Apart from a few youthful oil field arrests and flirtations with the Fort Worth underworld during Prohibition, he had little direct criminal involvement. But like few other writers, Thompson understood the dark side of human nature and those on society’s fringes—luckless losers adrift in a twilight world of cheap hotels and alcohol, blackmailers and grifters, psychopaths, serial killers, and crooked cops. His novels pulsed with characters driven by lust, obsession, betrayal, revenge, and violence. Readers were apt to encounter a deranged, criminal narrator with an outer normality masking simmering, inner turmoil. Some closest to the author felt that much of his characters’ loneliness, repressed anger, and alienation came out of a personal youthful animosity toward his father and others. Of his writing, he once said, “There are thirty-two ways to write a story, and I’ve used every one, but there’s only one plot: Things are not as they seem.”

Artist Jerry Bennett illustrated this portrait of the writer Jim Thompson for Oklahoma Today.

James Myers Thompson was born in 1906 in Anadarko, Oklahoma Territory, in a small room just above the county jail. A year later, his father, Caddo County Sheriff “Big Jim” Thompson, came under suspicion for embezzlement of county funds. After putting his wife and young son on a train back to her family in Nebraska, Big Jim fled by horseback to Mexico.

After two years, with help from his old lawman friend Bill Tilghman, the elder Thompson was able to reunite with his family in Oklahoma City—after which he spent a lifetime chasing speculative dreams. As his father’s fortunes rose and fell in the Texas oil fields, young Thompson grew up largely without him, moving between Oklahoma City; Burwell, Nebraska; and Fort Worth.

At age fifteen, to help support his family, he found work as a gofer and junior reporter at The Fort Worth Press, where he received a few writing credits. While in high school, he began moonlighting as a bellhop at downtown Fort Worth’s Hotel Texas. It was there, working the eleven-to-seven shift, that he came to intimately know the workings of life’s darker corners, which were to inform his later writing.

During the 1920s, the Hotel Texas was a prime party venue for big oil, rodeo, and livestock gatherings. While his monthly salary was only fifteen dollars, young Thompson soon learned he could make much more in tips from hotel patrons by procuring bootleg liquor and drugs, pimping, and—at six-feet-four, quietly handsome, and bearing resemblance to a young Gary Cooper—serving, at least once, as a male escort. He learned gambling and the art of the small-time con from some of the best. While still in high school, he was regularly bringing home $300 a week from his hotel job.

Deprived of sleep, he eventually began using alcohol and cocaine to help him through his work nights, along with a sixty-cigarette-per-day habit that remained throughout his life. At nineteen, suffering from bleeding ulcers and having dwindled down to a hundred pounds, he collapsed and was hospitalized for nervous exhaustion, tuberculosis, and alcoholism. He spent nearly a year recuperating back in Nebraska. His mother’s family there blamed his father’s failed business schemes for placing an undue burden on his son.

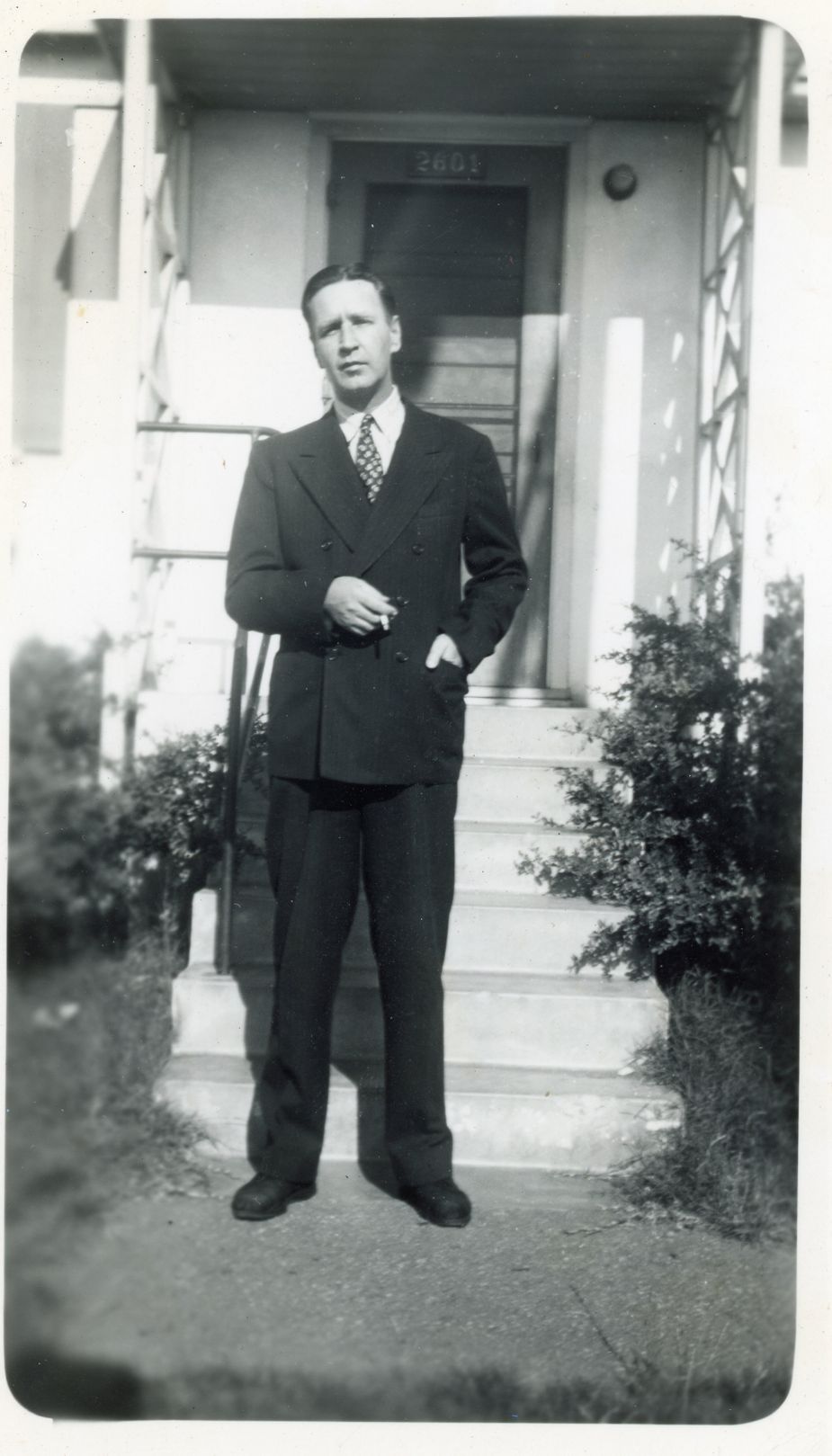

Thompson drew inspiration from his own hardscrabble life and close encounters with the criminal underground to write some of the most memorable crime noir fiction of the twentieth century. Photo courtesy Jami Reed

Thompson showed early promise as a writer, but by his junior year in Fort Worth, he’d fallen two grades behind and left school to work in the Texas oil fields, never having graduated. He spent the next few years as a drifter and oil field worker. When he was twenty-three, his written account of life in the oil fields appeared in Texas Monthly magazine. Impressed with his writing, the editor was instrumental in arranging Thompson’s admission into the University of Nebraska through its special program for adult students.

Viewed by most as a quiet loner and working a full slate of part-time jobs, Thompson struggled with the general curriculum but excelled in his writing courses, with a few short stories gaining national recognition. In his second year, he met and married Alberta Hesse, and later that year, feeling the economic pinch of the Depression, left school to find work. Leaving his pregnant wife with her family, he hopped a boxcar and—returning only briefly for the birth of his daughter—spent the next two years working harvests, oil fields, and odd jobs across the Midwest and writing pieces for trade journals. Through the Depression years, he earned a living as a lumberjack, bill collector, door-to-door salesman, gold buyer, and explosives man.

In the early 1930s, his family joined him in Fort Worth, where he worked a hotel job by day and wrote by night. In 1935, True Detective magazine published his first crime story. During the ’30s and ’40s, more than seventy crime magazines appeared on newsstands, and Thompson wrote for most of them—the only major author of the time to hone his craft primarily on true crime.

For a 1935 magazine assignment, he moved with his family to Oklahoma City, where he stayed on to help direct the new Federal Writers’ Project in Oklahoma. Like many writers of his day, his pro-labor views aligned with those of the country’s emerging Communist movement, to which he belonged for a few years. Openly critical of the state government’s corruption and treatment of miners and railway and packinghouse workers, he and other project writers fell into disfavor with the governor and others. Soon after joining with fellow activists Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger for a public sing-along in Oklahoma City’s shantytown district, he and his family left for California.

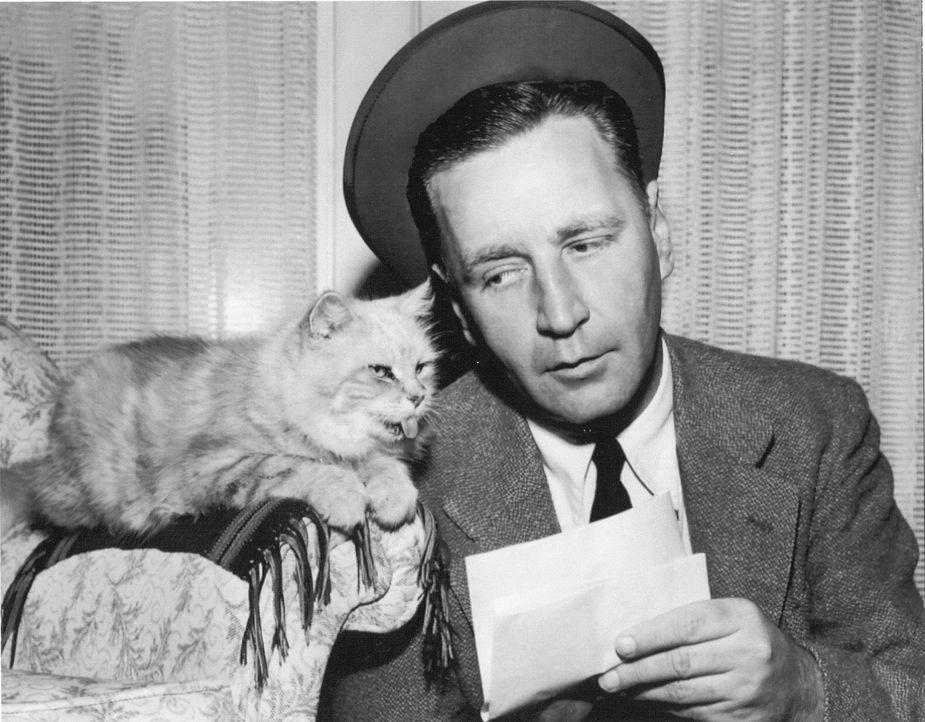

Thompson poses with his cat, aptly named Deadline. Photo courtesy Jami Reed

Unable to find suitable work and struggling with alcoholism, Thompson eventually sent his wife and children to live with her family in Nebraska and went to New York City to look into a job opening. There, his friend Woody Guthrie, after reading sample chapters of Thompson’s unfinished novel, arranged a meeting and publication of the book, along with two others. His first, Now and on Earth, was essentially a dissection of an American family through the Depression years, modeled largely on his own. Like his other early novels, it had little to do with crime and sold poorly.

With his family joining him once again in California, he spent most of the 1940s working as a factory manager and newspaper writer while continuing work on novels and crime magazine pieces. But as Robert Polito wrote in his award-winning biography Savage Art, “Although his legend glows with the heat of his relentless productivity, Thompson wrote as he drank . . . in binges.”

He would disappear for days at a time, and he was hospitalized twenty-seven times over a three-year period for problems related to his six-pint daily drinking habit. An editor once remarked, “Jim was a dreadful problem. But, my God, once you dried him out, what a talent!”

Thompson’s lasting legacy as a writer began rather late, at age forty-three, with publication in 1949 of his first mass-market paperback crime novel, Nothing More Than Murder. In an astounding nineteen-month period of sobriety between 1952 and 1954, he penned twelve successful crime novels. His publisher gave him free rein, stating, “You unleash a guy like that, you simply don’t try to direct him.”

In the 1950s, his books routinely sold out every copy of their initial printings of 200,000. Director Stanley Kubrick called his 1952 classic The Killer Inside Me, “probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered.”

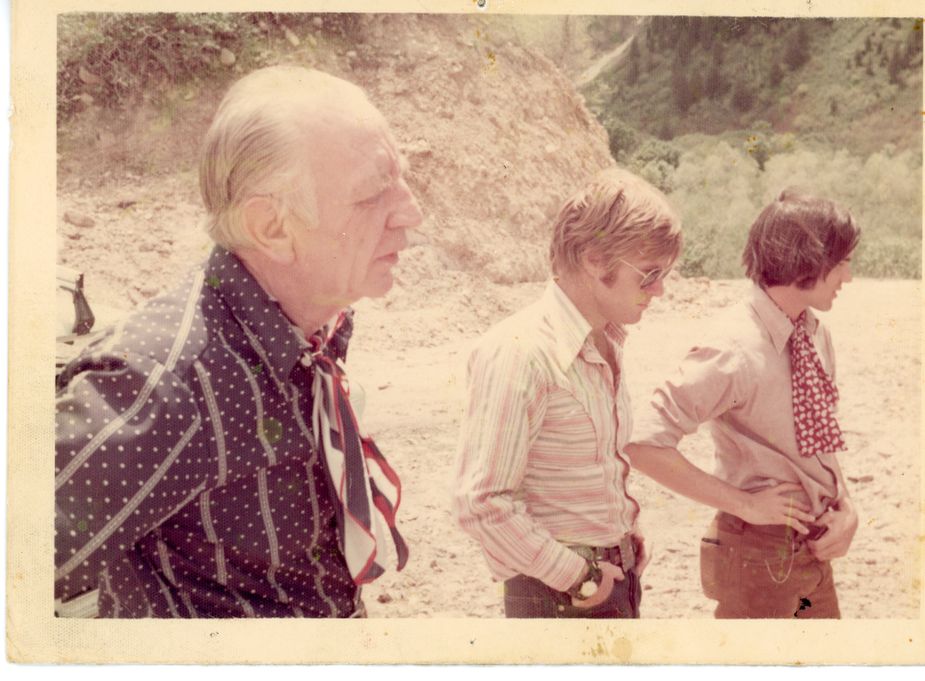

In 1970, Robert Redford helped Thompson get hired to write a script, but the film—about a Depression era drifter—never made it to production. Photo courtesy Jami Reed

Thompson was close to his editor at Lion Books, Arnold Hano, and his drinking resumed with Hano’s departure in 1955, after which he’d write only three notable novels. In 1956, Kubrick hired him to write the script for The Killing, now largely regarded as a film noir classic. The following year, he cowrote the screenplay for Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. While two of his novels were made into films during his lifetime, he always felt somewhat misunderstood and shorted by Hollywood. Out of financial necessity—though he hated writing for television—he wrote episode scripts for Combat, Mackenzie’s Raiders, Tales of Wells Fargo, and Dr. Kildare.

By his late sixties, Thompson’s health had largely played out from smoking and drinking, and he was plagued by debt from hospitalizations and medical costs. Ironically, he spent most of his life nearly broke, with the bulk of his best work written under financial duress. Despite impressive sales of his crime novels, paperback originals during his prime years had sold for less than a dollar. His last notable screen credit had been in 1957, and his last important novel had appeared in 1964. Largely forgotten, none of his books remained in print in America.

He’d often voiced his conviction that life doesn’t have a Hollywood ending. On Christmas Day, 1976—in the aftermath of a heart attack and two recent strokes—he asked to be driven down to the ocean, where he sat for a time, looking out at the Pacific. He then stopped eating, confiding to his wife, Alberta, “I don’t know whether I’ll ever be able to write again, and I couldn’t stand that.”

He told her to safeguard all of his writings and copyrights, because he felt his work likely would be more appreciated “. . . after I’m dead about ten years.” He died about three months later and was cremated.

But as he envisioned, beginning in the 1980s—in one of publishing’s more improbable turnarounds—much of his work was reprinted. Two of his novels were adapted for film in France, as were five more in the United States—including The Getaway, The Grifters, After Dark My Sweet, and Hit Me. A 2010 adaptation of The Killer Inside Me was filmed in Oklahoma and starred Jessica Alba and Casey Affleck. Two Thompson biographies appeared in the 1990s, along with a Tom Cruise-directed television adaptation. By the end of the decade, he’d surfaced from nowhere into the cultural mainstream as an enduring and significant American writer. The Killer Inside Me has been published in more than twenty languages.

Thompson’s trademark dark realism was, arguably, ahead of its time. Warner Bros. had turned down his script idea for Oklahoma’s Osage murders a full eighty years before Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. To quote film critic David Thomson, “Think of Jim Thompson as one of the finest American writers, and the most frightening—the one on best terms with the devil.”

.png)