Art Supreme

Published July 2022

By Megan Rossman | 10 min read

The Oklahoma Judicial Center is an unlikely art destination. This sprawling building within the Oklahoma State Capitol Complex is the home of the Oklahoma Supreme Court, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, and the administrative office of the courts. It’s the brick-and-mortar epicenter of Oklahoma law. However, within its stately walls also resides one of the best and most unexpected round-ups of Native American art in Oklahoma. Acee Blue Eagle, Eric Tippeconnic, Jeri Redcorn, Woody Crumbo, Poteet Victory, Mike Larsen, and Benjamin Harjo are but a few well-known names on display among an inventory of more than two hundred works. While the bulk of the collection is Native American, it also includes non-Native artists with Oklahoma roots like Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, Oscar B. Jacobson, Harold T. Holden, and Ryan Cunningham.

Painted in 2017, "Briefcase Warrior" by Comanche artist Eric Tippeconnic is one of the newest works on display at the Judicial Center. Photo by John Jernigan

As Justice Yvonne Kauger, who’s served on the Oklahoma Supreme Court for thirty-five years and headed the art committee in 2009, will tell you, assembling this body of work—and even getting the building in which its housed—was a time-intensive labor.

“It took thirty years to get this building, three bond issues, and 250 dozen cookies,” says Kauger, who persistently campaigned—with the assistance of homemade baked goods—to be relocated to the court’s current digs.

Talihina native Les Berryhill's "Bison Skull" took 4 to 5 hours a day for 6 months to complete. It contains thousands of beads sewn one at a time to buckskin, which then is attached to the skull. Photo by John Jernigan

The Wiley Post Building—as those digs are known—was designed in part by State Capitol architect Solomon Layton’s firm and was home to the Oklahoma Historical Society from 1930 to 2005. It didn’t become the Judicial Center until 2011, after an extensive thirty-five-million-dollar renovation. Although many interior elements were updated and redesigned, an original mural at the top of the staircase on the third floor laid the groundwork for the building’s Native American influence.

"Hump"—titled for the bison hump medicine shield the figure holds—was painted by Matthew Bearden, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation whose ancestry also includes Kickapoo, Blackfoot, and Lakota Sioux. Photo by John Jernigan

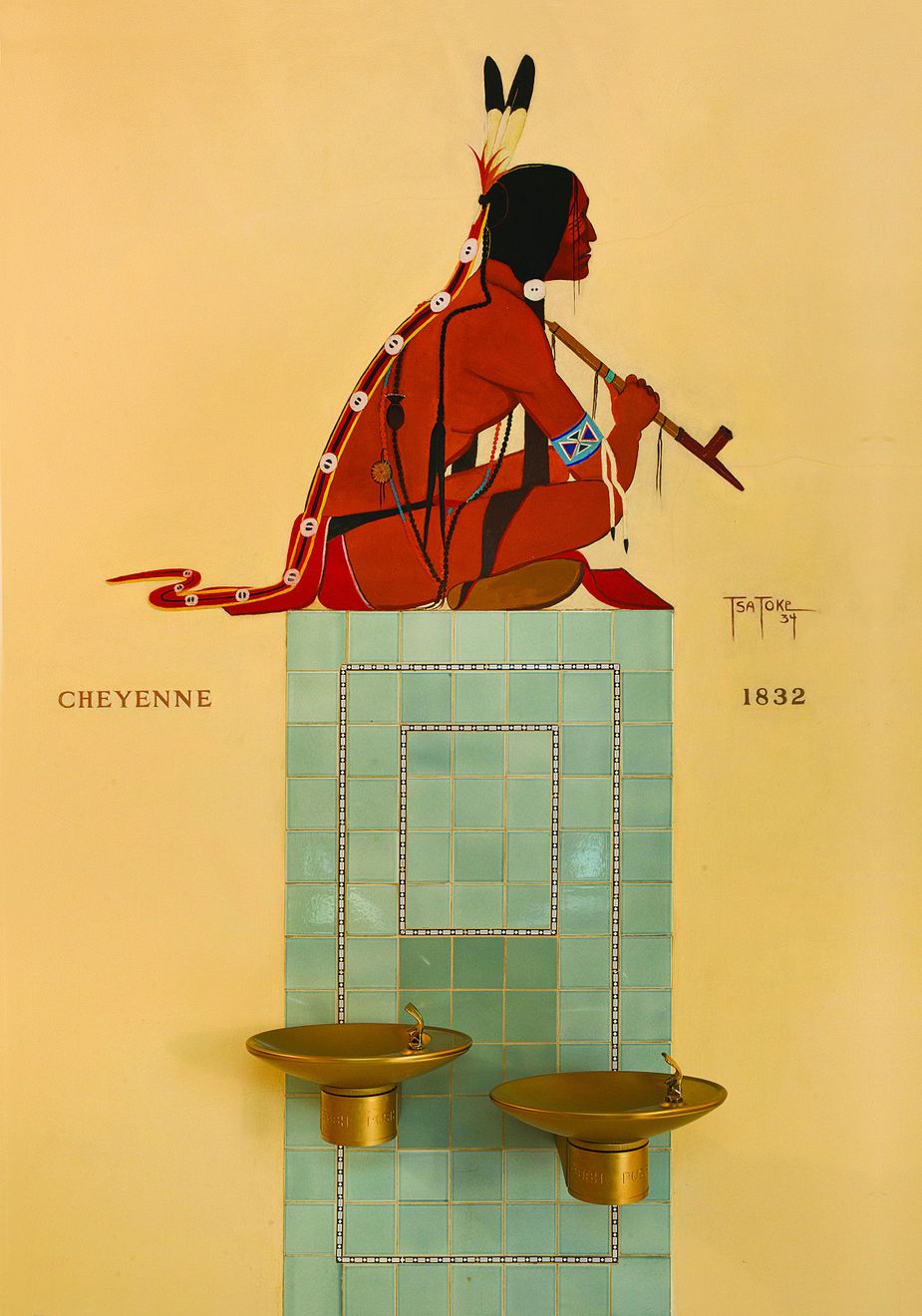

It was on this wall in 1934 that Monroe Tsatoke and Spencer Asah of the famed Kiowa Six painted a series of eight Cheyenne, Choctaw, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage, and Secotan figures as a Public Works of Art Project. The Secotan man stands out in particular because of his more unfamiliar tribal identity, but as Gayleen Rabakukk suggests in the 2014 book Art of the Oklahoma Judicial Center, Tsatoke surely meant it as a statement:

This panel by Kiowa Six artist Monroe Tsatoke is part of a mural on the third floor that was commissioned in 1934. When Tsatoke died, Spencer Asah created the final two paintings. Photo by John Jernigan

“By 1650, the Secotan tribe had all but disappeared,” Rabakukk writes. “By including the Secotan with the other tribes that were relocated to Indian Territory in the 1800s, Tsatoke may have been warning Oklahomans that the others were all in danger of a similar fate.”

Caddo potter Jeri Redcorn's piece here is one of a trio known as "Three Sistern of the Supreme Court," which is dedicated to justices Alma Wilson, Yvonne Kauger, and Noma Gurich. Photo by John Jernigan

It’s no small feat that this priceless historic record has managed to survive in a government building for eighty-five years. Kauger was inspired by its longevity, and since she is a long-time art collector, she and her team culled the Oklahoma History Center’s archives for more Native American works to display in the building. Kauger and staff attorney Kyle Shifflett placed every work themselves.

“I went through every piece over there and took what I call the good stuff,” she says.

"Fire" is one of three paintings by Cheyenne and Arapaho artist Brent Learned in the judicial center’s first floor conference room. Photo by John Jernigan

Treasures here include a pair of giant canvases painted with bold ceremonial figures by Stephen Mopope, another member of the Kiowa Six; a dark, moody portrait of Comanche chief Quanah Parker by A. Shaw, an artist about whom little is known; a variety of 1920s pueblo pottery from Santa Fe; and a 1901 painting of Sequoyah—creator of the Cherokee syllabary—by Narcissa Chisholm Owen.

All told, about 65 percent of the center’s collection is on permanent loan from the Oklahoma Historical Society. The remainder has been donated or purchased by way of the Oklahoma Art in Public Places Act, which requires 1.5 percent of the budget of any state capital improvement project be invested in public art.

Three unique masks by Cherokee artist Dan Corley are on display at the center. Each begins with a clay mask, which he covers with leather before adding paint, beads, and feathers. Photo by John Jernigan

Before coming inside, visitors can walk through the Veterans Memorial on the north side of the Judicial Center, which honors Oklahomans who served in American war efforts from the First World War through Vietnam. This large-scale series of plaques, reliefs, flags, and statuary, designed primarily by Navy veteran Jay O’Meila, also features sculpture work by Pawhuska artist Bill Sowell.

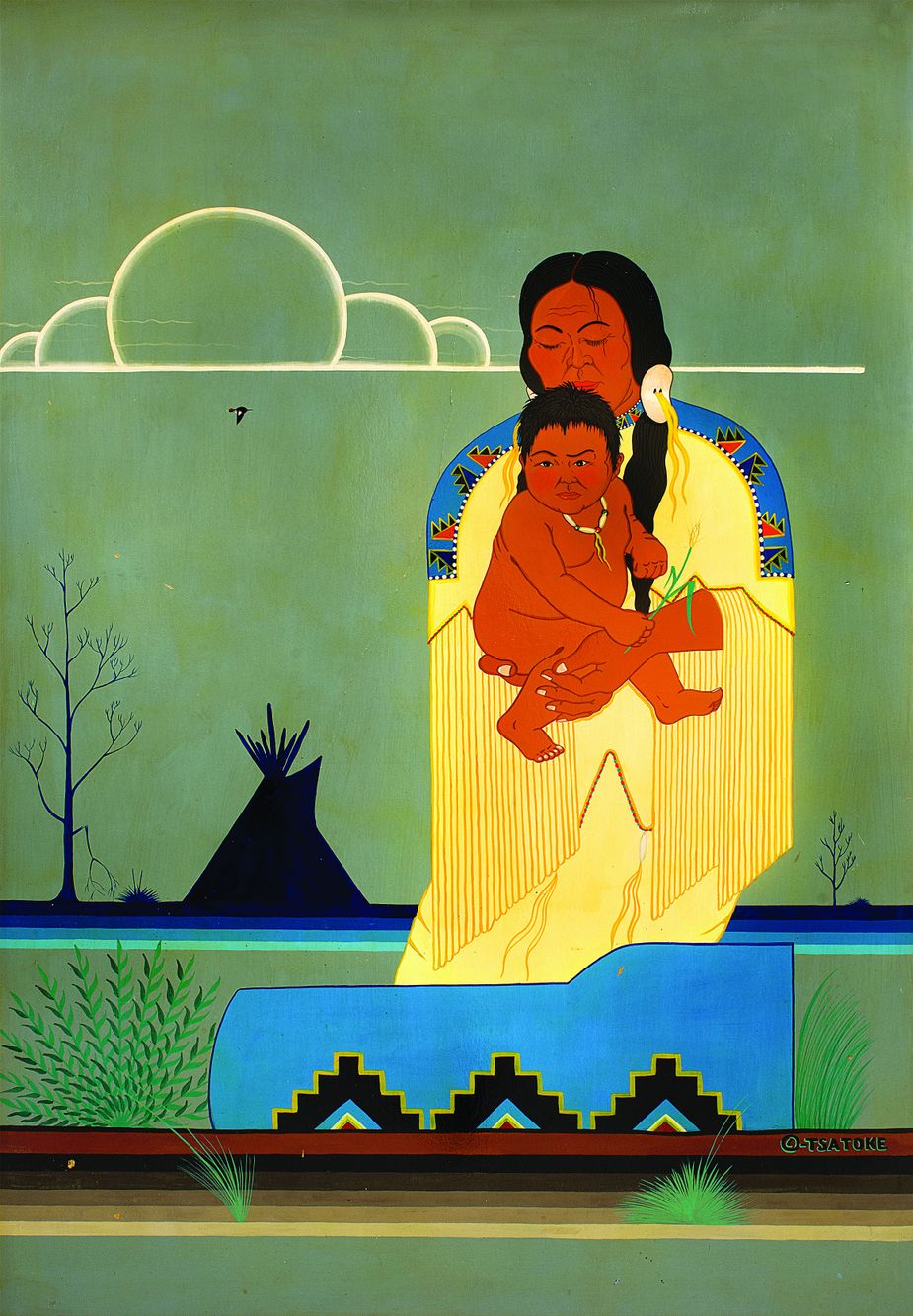

Monroe Tsatoke, member of the Kiowa Six, created this untitled painting that hangs outside Justice Yvonne Kauger’s judicial chambers. Photo by John Jernigan

Once inside, on the first floor, viewers will see Matthew Bearden’s jewel-toned Osage warrior looming larger than life on the south side of the hall and Jean Richardson’s ethereal Light Horsemen standing watch to the north, while G. Patrick Riley’s twenty-eight-foot stainless steel Eagle spans the atrium wall from the first to third floor. In the alcoves and meeting rooms on the second floor, visitors will find more works by Jennifer Cocoma Hustis, Dana Tiger, James Auchiah, Woody Big Bow, and Sharron Ahtone Harjo. Near these are a massive portrait of the Kiowa Six by Mike Larsen in the reception area and a glass tipi by D.G. Smalling. Passing the building’s signature murals on the third floor, visitors will see a painting of Cherokee Andy Payne, who ran 3,424 miles in 1928 to win the International Trans-Continental Footrace; Les Berryhill’s intricately beaded bison skull; and Caddo pottery by Jeri Redcorn, whose work was displayed in the Oval Office during the Obama administration. Because visitors enter one floor up, it’s easy to forget there’s also a lower ground floor in this building, which can be accessed from the first floor staircase in the lobby. Here, guests will find pieces by Joan Marron, Jane Semple Umsted, Robert Redbird Sr., and Benjamin Harjo Jr.

Not much is known about A. Shaw, who created the portrait Quanah Parker, which depicts the famous Comanche chief. Cherokee Troy Anderson sculpted the bronze buffalo titled "Not Forgotten." Photo by John Jernigan

This is an under-the-radar art experience, to be sure, where state business is conducted in well-curated hallways and meeting spaces. But art lovers are missing out if they don’t make time to wander this space for an afternoon. Around every turn, sculptures, pottery, and paintings occupy walls, tables, bookcases, and pedestals, bringing world-class art with no cost of admission to the people of Oklahoma.

The Oklahoma Judicial Center is open 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday. 2100 North Lincoln Boulevard, (405) 556-9300.

.png)